(JTA) — Last month, Francois Amalega Bitondo was standing on a Montreal street, megaphone and cellphone in hand, protesting against COVID-19 vaccines. A bright yellow six-pointed star stood out against his black T-shirt.

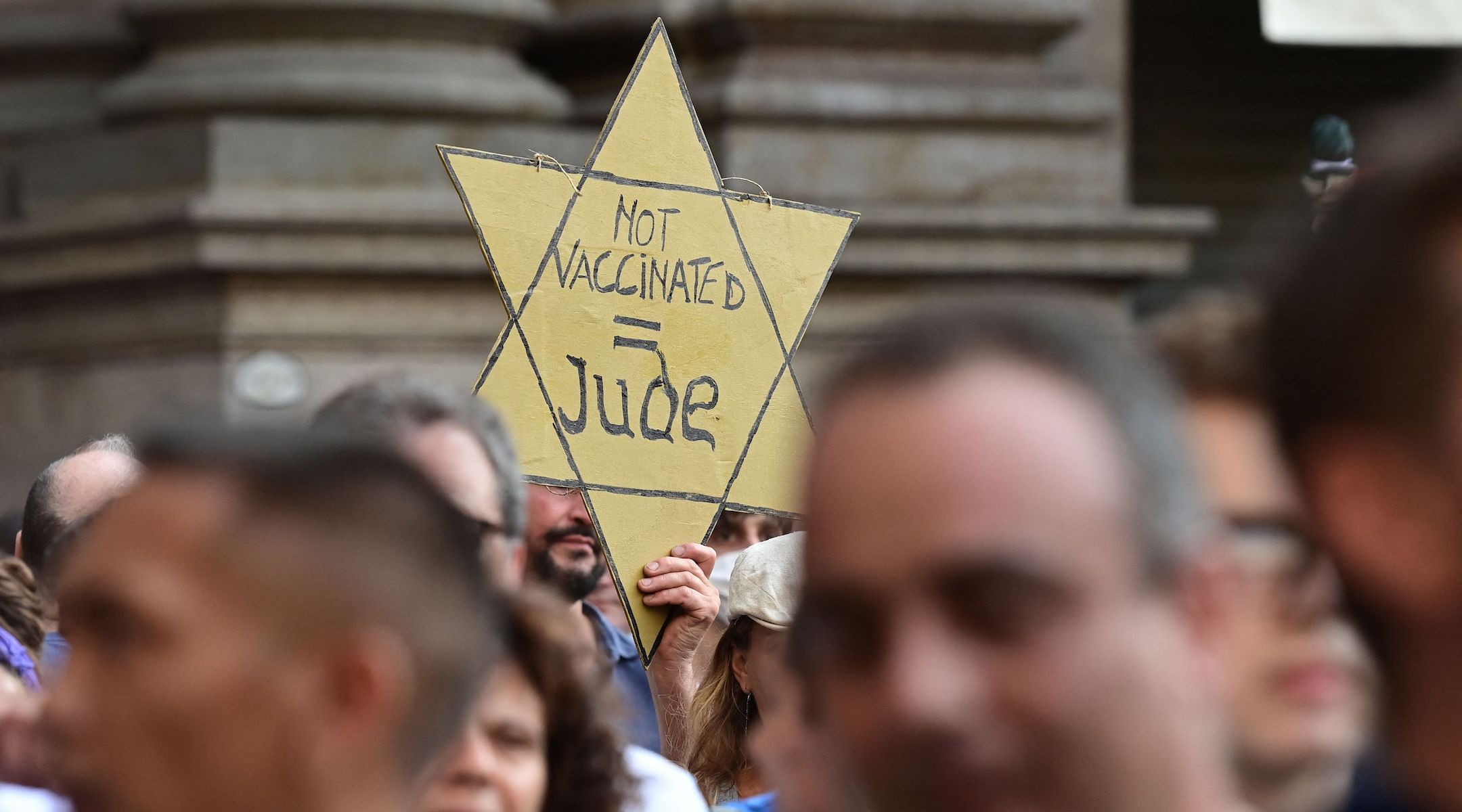

The star, which read “unvaccinated,” was an explicit reference to the yellow Stars of David that Jews were forced to wear during the Holocaust. Others in the crowd were wearing them, too. Their implication: Those who refuse to be vaccinated are facing the same oppression as Jews did in the 1940s.

The message and badge put Bitondo and his fellow protesters into the company of a growing cadre of COVID-19 vaccine skeptics around the world who have invoked the Holocaust as they rail against regulations that increasingly marginalize those who choose not to be vaccinated against the virus.

In the days following the Montreal protest, Bitondo told a French journalist that his yellow star was “here to stay” and Quebec’s anti-racism minister criticized anti-vaxxers who don the symbol.

Then Bitondo called the local Holocaust museum — and changed his mind.

In a Facebook video posted Aug. 19, Bitondo said he now understood why so many Jews objected to the symbol and announced he would not wear the yellow star anymore. He instructed his followers not to, either.

“I decided that if there are people in the Jewish community that are shocked, it’s not good,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Bitondo’s reversal illustrates a possible strategy for those who object to comparisons between anti-vaxxers and Holocaust victims. But other thoughts also shed light on why the comparisons have spread and how deeply rooted the sentiments behind them may be.

Though Bitondo may not want to alienate Jews, he does think the plight of anti-vaxxers is similar to the threat that Jews faced under Nazi rule.

“What they want to install from the first of September is exactly like the first of September 1941, when the Jews were supposed to wear the star,” Bitondo told JTA about Quebec’s launch of a “vaccine passport” on Sept. 1.

He added, “The government of Quebec is following a way that resembles what Hitler was doing, dividing the society in groups.”

Among anti-vaccine protesters, Bitondo is far from alone in drawing a comparison to the Holocaust. Yellow stars reading “no vax” in faux-Hebrew script appeared during a measles outbreak in 2019, and the trend has accelerated this year as the advent of COVID-19 vaccines – and campaigns to persuade people to take them — have caused conflicts worldwide.

Yellow stars have been deployed as a symbol in anti-vax demonstrations across the United States and internationally, from a City Council meeting in Missouri to a speech by a local Washington state official to protests in Germany, France and elsewhere.

Anti-vaxxers and their allies have invoked Nazi Germany in other ways as well. Speakers at a recent St. Louis County Council meeting compared mask mandates and other COVID messaging to the Nazis. At school board meetings on mask mandates in the Detroit and Pittsburgh areas, some in attendance gave Nazi salutes. Last month, two Republican congresswomen, Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert, compared federal vaccination efforts to Nazism.

Last week, the head of Chicago’s police union railed against the mayor’s plan to require officers to be vaccinated.

“We don’t want to be forced to do anything. Period,” the union chief said. “This ain’t Nazi f***ing Germany: ‘Step into the f***ing showers. The pills won’t hurt you.’”

Since then, a Kentucky congressman drew criticism for tweeting, then deleting, a meme using the tattooed wrist of a Holocaust survivor to condemn vaccine mandates, and a Republican lawmaker in Maine compared health care workers administering vaccines to Joseph Mengele, the sadistic doctor at Auschwitz.

Holocaust scholars and antisemitism watchdogs agree that the stars and other analogies are offensive and trivialize an immense tragedy. Those who choose to forgo a vaccine are not the same as a group oppressed due to their ethnicity, they say, and public health restrictions are not the same as genocide. And being barred from a gym is not the same as being ghettoized and gassed at Birkenau.

“Historically speaking, the comparison makes no sense,” said Frances Tanzer, a professor of Holocaust studies at Clark University. “This is a public health measure. This is not a foundational part of some identity.”

But Tanzer said that in the popular imagination, Jews during the Holocaust have become the “paradigmatic victim.” So for anti-vaxxers and others who see themselves as oppressed, Jewish suffering during the Holocaust “allows them to think about themselves as the ultimate victim, despite the fact that historically there is no comparison.”

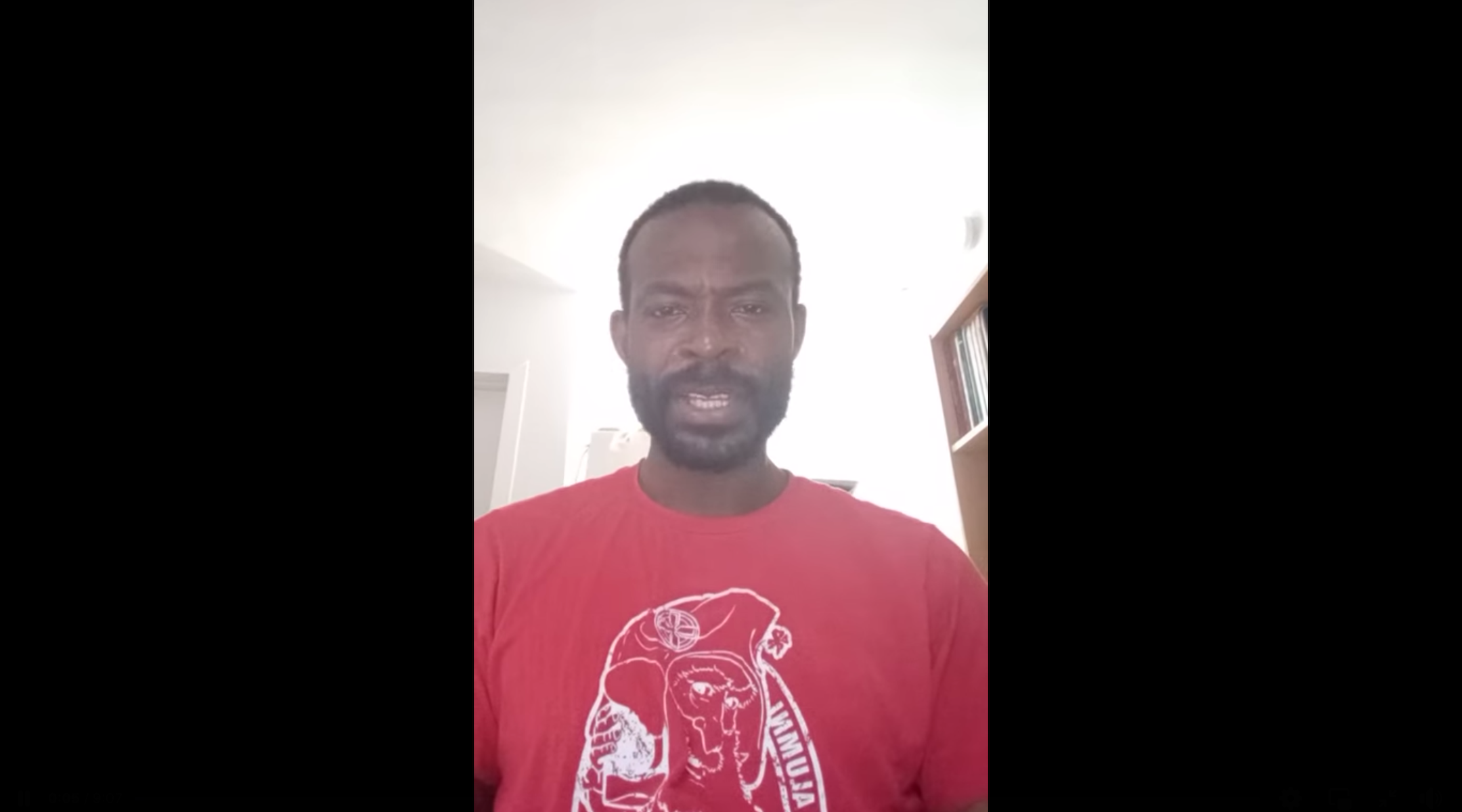

Francois Amalega Bitondo, a leader of anti-vaccine protests in Montreal, told his followers not to wear yellow stars following a discussion with the head of the local Holocaust museum. (Screenshot from Facebook)

Of the many anti-vaxxers to don the yellow star, Bitondo appears to be one of the few to take proactive, public steps to understand why so many people objected to it. In August, following the wave of condemnations for his statements, he called Daniel Amar, executive director of the Montreal Holocaust Museum.

Amar told JTA that Bitondo was polite and respectful, insisting that he didn’t hate Jews and even wishing Amar “Shabbat shalom” at the end of the call. Amar explained to him how offended survivors were when they saw images of anti-vaccine protesters wearing the star, and how the stars implied a minimization of the Holocaust’s horrors.

“He was hurt by the accusation, so it was an honest discussion,” Amar said. “It was clear the guy was not at all antisemitic. It’s irrational, it’s wrong, it’s crazy, but they [anti-vaccine activists] are not motivated by the hatred of the Jews.”

That evening, Bitondo recorded a 9-minute video explaining why he would no longer wear the star. He also canceled a protest that he had planned in front of the Holocaust museum for the next week.

Speaking to JTA, Bitondo said that he chose to stop wearing the star because “the focus [of public attention] was on the star, not the requests” of the protesters. He also said he didn’t want to hurt the Jewish community.

“We need to be united against the threat that is coming,” he said. “So if the Jewish star will shock them instead of coming together so we can have a democratic debate, I saw it was good to remove the star.”

But Bitondo doubled down on the comparisons between anti-vaxxers today and historically oppressed and abused groups. He said that as a Black person, he also believes there is a parallel between the enslavement of Black people and how anti-vaxxers are being treated.

He acknowledged that “we have not reached that extent” yet and that anti-vaxxers haven’t been enslaved or exterminated. But Bitondo fears that’s where things may be headed.

“Once the Jews were considered inferior, the Blacks were considered inferior, the Jews were put in concentration camps, Blacks were forced to be beaten and be slaves and were not considered human,” he said. “Today, the things that are going on, it feels like we’re following the same pattern.”

Those statements could have disheartened Amar, who was proud that his phone call with Bitondo led the activist to remove the yellow star from his shirt. But the museum director said he has no regrets.

“The guy is wrong,” said Amar, who reiterated that the comparison between anti-vaxxers and Holocaust victims is “completely foolish.” But he doesn’t want to spend even more energy condemning Bitondo. After all, Amar said, Bitondo did agree not to wear the star. And at least he understands that the Jews were victims and is trying to identify with them.

“He doesn’t see it [as] a Nazi symbol,” Amar said regarding the yellow star. “He sees it [as] a symbol of the Jewish suffering, which is a big difference. In his mind, he’s not wearing it because he wants to support Nazis. He’s doing it because he feels like a Jewish guy during the Holocaust. … He loves Israel, Jewish community, he loves Jewish people.”

Amar added that one phone call isn’t enough to teach someone about the Holocaust and the proper way to discuss it in the public square. He hopes Bitondo will visit the museum to learn more and about the risk “of trivializing the Shoah.”

Both Amar and Tanzer said the incident is an argument for more Holocaust education, not an example of its limited use.

“I don’t think anyone can really learn so much about the Holocaust just from one meeting,” Tanzer said. “It might change someone’s mind about something a little bit, but obviously it would be almost absurd to think that a single meeting would radically transform someone’s perspective on anything so complicated.”

Tanzer added that because a sense of victimhood is central to anti-vaxxers who appropriate Holocaust symbols, any education would have to address that as well, even if the protesters understand that wearing yellow stars hurts their cause.

“He doesn’t want to be embarrassed and he doesn’t want to be tagged as something he doesn’t think he is, which is an antisemite, but he also still believes that the comparison holds,” Tanzer said. “Any Holocaust education that’s going to change that would have to go pretty deep and would maybe have to address things far beyond the Holocaust because it would have to address his sense of victimization.”

Amar hasn’t seen Bitondo invoke the Holocaust publicly in the weeks since their conversation. But if he does go back to making public analogies to the Nazi era, he wouldn’t be the first.

In June, Greene toured the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and apologized for comparing COVID mandates to the Holocaust. About three weeks later, the Georgia lawmaker said federal vaccine efforts were being conducted by “medical brown shirts,” a reference to a Nazi militia.

But Amar said that no matter the ultimate result, he believes trying to educate people is always a worthy endeavor.

“It’s never a waste of time,” he said. “We have nothing to lose trying to explain to them that they’re making a big mistake and what they’re doing is wrong.”