Hanukkah should have disappeared a long time ago.

For centuries, scholars have noted that there is virtually no mention of Hanukkah in the Mishnah, and very little in the Talmud. (By contrast, Purim merits an entire tractate of the Mishnah.) Rabbis and scholars have proposed many clever theories as to why this is so. The Chatam Sofer argues that it is because Rabbi Judah the Prince, the editor of the Mishnah, was a descendent of the Davidic Monarchy; he had a grudge against the Hasmonean dynasty, (the family of the Maccabees), for grabbing the monarchy away from his own family. Another common theory is that later generations of the Hasmonean dynasty persecuted the Pharisees; so the Rabbis of the Mishnah, their successors, were not too enthusiastic about this Hasmonean-era holiday. Rabbi Reuben Margolies offers a fascinating theory that the Rabbis actually engaged in self-censorship. They didn’t want to talk too much about Hanukkah, afraid that a holiday commemorating a Jewish rebellion against foreign rule would antagonize the Romans.

There is however a much simpler answer. The Rabbis of the Mishnah were deeply ambivalent about Hanukkah, unsure if it should still be celebrated in their time. The Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 18b) wonders why Hanukkah was still observed; Hanukkah should have been rendered obsolete with the destruction of the Temple. Hanukkah is, as the Ran explains, a celebration of the rededication of the Temple; that is the origin of the word “Hanukkah,” which means “to dedicate.” Maimonides adds that it also celebrates the return of Jewish sovereignty. In 70 CE, neither the Temple nor sovereignty remained.

Many people must have felt that in exile, Hanukkah should be downplayed, or even canceled. After the catastrophic destruction of the Second Temple, celebrating Hanukkah would only highlight what had been lost, adding insult to injury. And that is why the Mishnah has very little to say about Hanukkah; it may not have been clear if Hanukkah would continue to be a holiday.

Yet despite this initial hesitation, Hanukkah held on and ended up taking an honored place in the Jewish calendar. As the Talmud explains, the practice of Hanukkah had become so well accepted among the rank and file, that the holiday could no longer be canceled

But what meaning could Hanukkah have after the destruction? Clearly, it would be something very different, not a celebration of what is, but rather of what could be.

And that is exactly what happened. In exile, Hanukkah became a yearly reminder that comebacks are possible.

In 586 B.C. E., with the destruction of the First Jewish Commonwealth, the Jews lost their independence. Even though the Temple was rebuilt under the sponsorship of the Persians, the Jews were at the mercy of whichever empire controlled the region; Persians, Greeks, Seleucids. After the victory of the Maccabees, sovereignty was restored to the Jews for the first time in over 400 years.

That simply shouldn’t have happened. Ordinarily, when a nation is exiled it disappears, and when it is powerless for centuries it assimilates. That is why the rebellion of the Maccabees defied the laws of history. Who knew that a comeback like this was even possible? And that may be the greatest miracle of Hanukkah.

This is why Hanukkah remained an important holiday for the Jews in exile. They could take heart that their Maccabees ancestors were able to succeed against all odds. Hanukkah taught them that defeat doesn’t equal destiny, and no matter how dire the circumstances, they must never give up. Hanukkah was now a tribute to the miracle of comebacks.

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (Hararei Kedem 172) makes the radical assertion that, although the Jews celebrated Hanukkah during the times of the Temple, they only began to light the Menorah after the destruction.

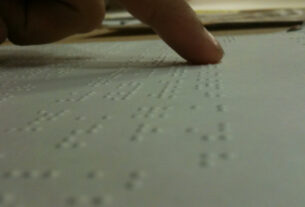

From this perspective, the Menorah functions as a reminder of the Temple. As they left behind the ruins of the Temple, Jews carried their own personal Hanukkah Menorahs, promising never to forget Jerusalem; they vowed that they would return again one day.

In exile, Hanukkah became a holiday of hope for Jews who dreamt of returning home, Menorah in hand.

Jews quickly learned that everyone else considered them homeless and hopeless, the relic of dying people who had overstayed their welcome on this earth. In the Middle Ages, Churches displayed sculptures of Ecclesia and Synagoga, a pair of female figures personifying the Church and the Jewish synagogue. Ecclesia is a young, attractive woman with a crown; Synagoga is bent over and blindfolded, clumsily dropping the Tablets of the Law from her hands. The rest of the world ridiculed the Jews for their absurd dreams, and told them that they should just give up.

But there was a far older sculpture that mocked the Jews, right in the center of Rome: The Arch of Titus. It depicts a procession of Jewish slaves carrying gold items from the Temple in Jerusalem; most prominent among them is the Menorah. The Arch was built over the actual route the Jewish slaves took on their way into Rome.

For Jews, the Arch of Titus was a place of humiliation. Stephen Fine, in his excellent book “The Menorah,” mentions a Papal ritual that lasted until the 1500’s. Each new Pope would call representatives of the Jewish community of Rome to meet them at the Arch. The Jews would present the Pope with a Torah scroll. The Pope would throw the Torah to the ground, saying, “I confirm this, but not your interpretation.” Some add that the Jews then had to kiss the ground the Pope stood on.

But the Jews ignored the bullying and insults. When Sigmund Freud visited the Arch of Titus in 1913, he wrote a postcard home saying: “The Jew survives it.” That is an understatement. Jews were determined to overcome it as well.

On December 2. 1947, a remarkable rally took place, only a few days after the United Nations voted to create a modern State of Israel. The Jews of Rome, as well as a throng of Holocaust survivors awaiting passage to Israel, assembled at the Arch of Titus. In a ceremony led by the Chief Rabbi of Rome, David Prato, those assembled sang the Hatikvah, and marched through the Arch of Titus in the direction of Jerusalem.

They had taken the Menorah back, ready for redemption.

Jews continued to light the Menorah during the bitterest years of exile. As they did so, they remembered that centuries earlier, against all odds, their ancestors had triumphed.

And they knew that if a people can make one comeback, they can always make a comeback.

And in 1948, they did.

Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz is the Senior Rabbi of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun in New York.