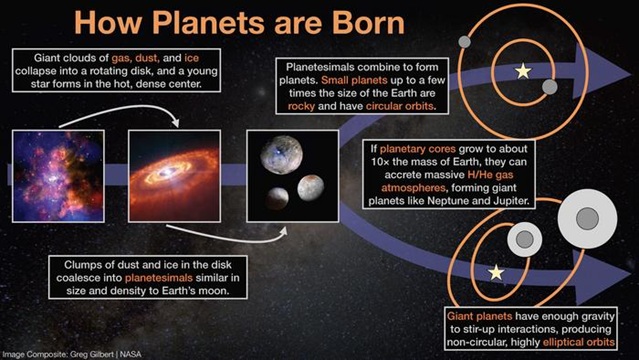

A planet’s orbit is a key characteristic, alongside its size and distance from its host star. While Earth follows a nearly circular orbit, many exoplanets—planets beyond our solar system—exhibit highly elliptical orbits. Now, UCLA astrophysicists have analyzed the orbital shapes of exoplanets ranging from Jupiter-sized giants to Mars-sized worlds, revealing a striking pattern: smaller planets tend to have nearly circular orbits, whereas larger planets follow paths about four times more elliptical.

This discovery, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that large and small planets may form through distinct processes.

“What we found is that right around the size of Neptune, planets transition from having predominantly circular orbits to frequently elliptical ones,” explained Gregory Gilbert, a UCLA postdoctoral researcher and lead author of the study.

The research team leveraged data from NASA’s Kepler telescope, which monitored 150,000 stars and detected exoplanets by measuring dips in stellar brightness—phenomena known as light curves. Through advanced analysis of these light curves, the scientists extracted precise details about exoplanetary orbits, providing new insights into planetary formation and evolution.

These findings shed light on the diversity of planetary systems and could help refine models of how planets develop across the galaxy.

One of the most challenging aspects of this project was ensuring every single one of the 1,600 light curves was modeled with care.

“If stars behaved like boring light bulbs, this project would have been 10 times easier,” said co-author Erik Petigura, a UCLA physics and astronomy professor. “But the fact is that each star and its collection of planets has its own individual quirks, and it was only after we got eyes on each one of these light curves that we trusted our results.”

This is where UCLA undergraduate Paige Entrican came in. Entrican built a custom visualization tool kit and manually inspected each light curve.

“Reviewing the data was a meticulous process that required careful inspection of all data products to ensure the validity of our results. Several times during this project, I identified failure modes that only affected 1% of all our stars. But we needed to update our analysis to be robust to these issues and go back and reprocess the entire data set,” Entrican said.

The eccentricity split coincides with several other iconic features in the exoplanet population, such as the high abundance of small planets over large planets and a tendency for giant planets to form only around stars enriched in heavy elements such as oxygen, carbon and iron. Astronomers call these heavy elements metals.

“Small planets are common; large planets are rare. Large planets need metal-rich stars in order to form; small planets do not. Small planets have low eccentricities, and large planets have large eccentricities,” Gilbert explained.

The coincidence of trends in abundance, metallicity and eccentricity points to two distinct pathways for forming small and large planets.