Steven Spielberg had already donated money to the Yiddish Book Center when he asked if the center’s founder, Aaron Lansky, might fly out to Los Angeles and drop by his office.

The filmmaker doesn’t usually meet with the beneficiaries of his philanthropy, Lansky told me recently, but wanted to explain his support for what is now the Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library at the YBC, an online collection of more than 12,000 Yiddish titles.

“’You have to understand,’ he said, ‘that what I do for a living is I tell stories,’” Lansky recalls Spielberg telling him. “’The idea that you have miles of Jewish stories that have yet to be told, that’s just irresistible to someone like me.’”

Spielberg may not even have been the first supporter of the Yiddish Book Center to find something, well, Spielbergian about an institution Lansky founded in 1980 as a then 24-year-old graduate student of Yiddish. More than one visitor to the YBC’s campus in Amherst, Massachusetts has compared the shelves and shelves of Yiddish books, rescued from dumpsters and the attics and basements of aging readers, to the colossal government warehouse seen in the closing scene of “Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

But Spielberg also seemed to understand what has driven Lansky, who is retiring this month as the center’s president. Lansky began by going door to door, asking elderly Jews and their offspring for the books they might otherwise have thrown away. The rescue project could easily have remained a warehouse of old books, dusty treasures moldering in the dark, occasionally accessed by scholars and hobbyists.

Instead, the collection of some 1.5 million volumes is only the foundation of an institution that now includes Yiddish classes, academic fellowships, a training program for translators, scholarly conferences, a publisher of books in translation, an oral history archive, a podcast and that digitized library of both classic and obscure Yiddish books.

“This is not just a matter of collecting books,” said Lansky, 69, recalling that he always had a vision beyond warehousing unread books. “It’s really a whole culture, it’s a whole civilization, it’s a whole historical epoch that needs representation, that wants to tell its story.

“And so after cataloging the books, very quickly, we started offering courses. We started teaching Yiddish language, and to make this world accessible. And that’s just continued ever since.”

Lansky’s decision to step down is both voluntary (his successor is Susan Bronson, the center’s executive director for the past 14 years) and gradual (he announced his retirement 16 months ago, and will stay on for two more years in the part-time role of senior advisor). He’s looking forward to writing, reading and thinking about the role of Yiddish in a Jewish world dominated by a Hebrew-speaking Israel and an English-speaking North America.

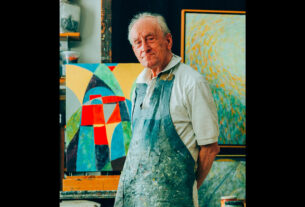

Architect Allen Moore’s design for the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts echoes the roof lines of a typical Jewish shtetl. ((JR) photo)

For much of the past 1,000 years, Yiddish was spoken by three quarters of the world’s Jews — a Germanic vernacular, seasoned with Hebrew, Slavic and Romance vocabulary, that bridged polyglot Jewish communities in Central and Eastern Europe and followed them to the far corners of the diaspora. The Holocaust decimated its native speakers, and assimilation and the rebirth of Hebrew as Israel’s language rendered it useless as an every-day tongue.

While many haredi Orthodox Jews speak Yiddish as a first language, the Yiddish Book Center celebrates and commemorates what Lansky calls “one of the most concentrated outpourings of literary creativity in all of Jewish history,” lasting roughly from the 1860s to the immediate aftermath of World War II. As newly emancipated Jews encountered modernity, they created a vast Yiddish literature both high-brow and low-brow — books, literary journals, newspapers, plays, songs and films. It was a literature, according to Lansky’s mentor, the Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse, “that, if it suffers from anything, suffers from its youthfulness, from the exaggerated emphasis on innovativeness and on modernity and originality.”

Lansky says Yiddish literature asks the essential question, “What does it mean for Jews to live in a modern world?” That question gnawed at him as a student, first at Hampshire College and later at McGill University, and led him to lead teams of collectors with wheelbarrows and pickup trucks.

“The idea that we were going to go reinvent ourselves in a modern world without reference to this vast literature seemed kind of foolish to me,” he said. “It was squandering an unbelievable treasure, yet very little at that point had been translated into English. Major Yiddish writers were hardly household names and women writers were almost entirely unknown in their own day.”

Lansky fondly recalls noshing in the living rooms of elderly Jews as they discussed their books and what each had meant to them. Eventually Lansky and his fellow volunteers went in teams of three — two to load the trucks, and one, the “designated eater,” whose job it was to sit with the donors and hear their stories.

An early estimate that they might find some 70,000 distinct volumes proved wildly modest. As the collection grew, Lansky earned a MacArthur fellowship, wrote a memoir about his efforts and, in 1997, opened the center on a 10-acre site on the campus of Hampshire College.

Lansky said people come to the center and the study of Yiddish for any number of reasons — nostalgia, scholarly interest, to discover a new aspect of their Jewish identity. Some younger Yiddishists have been drawn to the radical politics that Yiddish-speaking Marxists, socialists, Bundists and anarchists brought from a turbulent Europe to the streets of American Jewish ghettos.

“Yiddish was like a Rorschach test in that everybody seemed to find in it what they were looking for,” he said. But whatever their impulse, Yiddish is “significant because it represents the evolution of the Jewish people over a rather critical time. It gives voice to Jewish values, Jewish mores, Jewish perceptions of the broader world.”

For younger Jews who come to study Yiddish at the center’s fellowship and summer programs, the language also offers wider possibilities for Jewish belonging. While the future of multiculturalism may seem precarious, most 20- and 30-somethings came of age in a world when students were encouraged to affirm their diverse identities. “I think that gives [Jewish students] motivation for wanting to understand themselves,” he said. “Yiddish was a language of marginality that still speaks very loudly, and people recognize that and see that as a voice which can speak just as relevantly to current issues. It still has resonance.”

Yiddish has also attracted young speakers who are disillusioned with Israel and Zionism. Lansky said that caused some tension after Oct. 7, when he issued a statement in support of Israel and some younger staffers objected. Lansky eventually called a meeting. “We sat at a big table,” he recalled, “and we just said this: First of all, we want to be very clear. We’re not monitoring your politics. We’re not trying to dictate your politics. Whatever you do when you’re on your own time is your own business. We’re not going to search your social media accounts…

“But this is who we are, this is what the organization stands for, and we’re not going to abandon Israel, especially at a time like this.”

Reproductions of book and magazine covers hang over the main book room of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, part of the center’s core exhibit, “Yiddish: A Global Culture.” ((JR) photo)

The Oct. 7 attacks also took place just a week before the center planned to unveil a reimagining of its core exhibit, “Yiddish: A Global Culture,” with displays on the wide reach of Jewish creativity in the arts, politics and culture. Lansky briefly thought about postponing the celebration, but changed his mind.

“I said, ‘Right now, Jews are feeling so alienated, so isolated, so pilloried in so many ways that we really do need to stand together, and people are going to need their own history and culture more than ever before,’” he recalled. “We were expecting 100, maybe 200 people. But on that day, in the aftermath of what had happened in Israel, 500 people showed up.”

Ultimately, those who came were seeking out exactly what had inspired Spielberg: the power of telling one’s stories.

“People were crying, because they were just so happy to have their own history,” said Lansky. “Because at a time like that, [other] people were suddenly redefining Jewish history. Now we have to know ourselves. We can’t defend ourselves if we don’t know who we are. And I think there’s never been more interest or more opportunity to do that than right now.”

On Sunday at 2 p.m., Lansky will present his valedictory talk as the center’s president, talking about its future and the future of Yiddish.

Lansky is under no illusion that Yiddish will be revived as a spoken language outside of the haredi Orthodox community. But both in the original and translation, Yiddish literature will continue to offer new possibilities for Jews and non-Jews to understand the “dialectic” of Jewish culture — religious and secular, holy and profane, triumphant and tragic.

“What I would put my money on is that Jews, as a people, can’t get by with religion alone,” said Lansky. “There’s also a day-to-day side of Jewish life. And that separation, I think, is quite critical. The most profound works of Jewish literature are those works that embrace that dialectic.

“So what I would like is that Jews need to know their own history. If we don’t know our own history, then others define it for us, and that’s a very dangerous thing.”

Keep Jewish Stories in Focus.

(JR) has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of (JR) or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.