Just before going into recess on Saturday, California lawmakers approved legislation to create new mechanisms to address antisemitism in public schools, sending the measure to Gov. Gavin Newsom after closed-door negotiations that saw its provisions significantly pared down.

If enacted, California would become the first state to create a statewide antisemitism prevention coordinator for public schools. Advocates hope the model could be replicated nationally.

Newsom has not said whether he will sign Assembly Bill 715, and his office has so far declined to comment to the media. Supporters are urging swift action, arguing that with schools already back in session, the bill’s provisions should be implemented as soon as possible.

AB 715 received near-unanimous approval, passing the state Senate late Friday in a 35-0 vote with five abstentions. Hours later. the Assembly voted 71-0 in favor, with nine abstentions.

If signed into law, the bill will establish a new state Office of Civil Rights that reports to the governor’s cabinet and create specialized coordinators to address different forms of discrimination. Among them will be the antisemitism prevention coordinator, tasked with training teachers and school administrators, tracking incidents and advising on accountability measures.

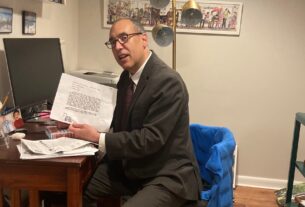

“This bill is about more than policy. It’s about protecting children, defending civil rights, and ensuring every student can walk into school proud of who they are,” said David Bocarsly, executive director of the Jewish Public Affairs Committee of California, which sponsored the bill and built a coalition of 70 Jewish groups in support.

Bocarsly called the vote a “historic stand against antisemitism in our schools” and underscored its significance by noting that he broke from religious custom to mark the moment.

“It’s not our typical practice to work on Shabbat, but with the 2025 legislative session closing, we wanted to share this late-breaking update from tonight,” he wrote in an email to supporters sent just after the Assembly tally was announced late Friday evening.

Lawmakers introduced the measure after Jewish organizations raised alarms about how antisemitism is surfacing in classrooms, particularly within some ethnic studies courses. Critics say students have encountered slurs, bullying and in some cases, instructional materials they view as biased against Jews. Several pointed to curricula that link discussions of race and power to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which they say can marginalize Jewish students.

Reports of antisemitic hate crimes have risen sharply in California in recent years. According to the state’s Department of Justice, religiously motivated hate crimes increased by 142% between 2015 and 2024, with Jewish people experiencing the majority of such incidents.

The bill’s path was far from smooth. The California Teachers Association, which represents more than 300,000 educators, strongly opposed the measure after it was first introduced, warning it could chill classroom discussions of controversial subjects, particularly around Israel, and could open the door to politically motivated complaints.

“AB 715 is the wrong response to a real problem,” Mara Harvey, a Jewish member of the CTA’s board, wrote in August about an earlier version of the bill, which she characterized as a vehicle for “right-wing, Trump-style censorship.”

The union’s resistance forced lawmakers to revise the bill. Most significantly, they removed a section that sought to define antisemitism through a list of examples, including ones where criticism of Israel might cross the line. Instead, the bill now draws from antisemitism strategies issued by the Biden administration and by Newsom last year.

But when the new language was unveiled, the union maintained its opposition, frustrating supporters such as Sen. Scott Wiener, a San Francisco Democrat who chairs the Legislative Jewish Caucus.

“I am disappointed that they’re still opposing the bill so aggressively. We’ve worked so hard to address their concerns,” Wiener told Jewish Insider last week. “It’s a narrower and more focused bill than it was before, but it’s still quite impactful and it sets some clear standards, and creates an antisemitism coordinator, so it’s a good bill.”

In another interview, Wiener said he eventually suspected that much of the pushback was in bad faith.

“I have increasingly come to the conclusion that if we had introduced a bill with three words — antisemitism is bad — a bunch of these people would still oppose the bill,” he told the J.

Theresa Montaño, a university professor and a member of the California Faculty Association, which opposes the bill, told KQED she worries that it could open the door to politically motivated complaints.

“This bill does nothing to challenge antisemitism,” Montaño said. “It does everything to create an environment that is divisive and that creates fear where teachers have to look around to see who in their classroom is likely to report them when they teach issues.”