Sometime in 2011 or 2012, racing in a cab to pick up my kids from school, I passed Philip Roth on the corner of West 79th Street and Central Park West. At the edge of the urban paradise where I ran each morning to keep my sanity — just as I had heard daily swims kept Roth sane at his Connecticut house — there stood my favorite novelist in a long overcoat, his left hand in one pocket, his right hand extended, palm up, leaning forward as he negotiated a lost cause with a beautiful woman.

“Negotiations and love songs are often the same thing,” another almost-Upper West Side neighbor, Paul Simon, once sang. The same could be said of Roth’s 27 novels — all negotiations of life, love, lust and self. He taught me more about all of these things than any writer I’ve ever read.

The only other time I saw him, Roth was speaking in Boston following the publication of his meditation on the death of his father, “Patrimony.” Having lost my own father this year, I’ve returned to Roth’s long goodbye to help me through mine. And as I hack my way toward completing a project far more personal than my previous book — this one a story about death, life, and love that aspires to be like one of Roth’s — I’m trying to determine whether it’s really me in my words, and whether I genuinely have something to say.

Roth’s “My Life as a Man” (1974) is guiding me — both the book itself, which opens with a “puppyish” son sizing up his “striving, hot-headed shoedog” father, and the way its title captures Roth’s entire canon: humor and gravitas channeled through gorgeous prose making sense of the male body and its desires; a man’s fantasies and flaws; and the precocious sensitivities and longings that one can squeeze out of a man’s life and onto a page.

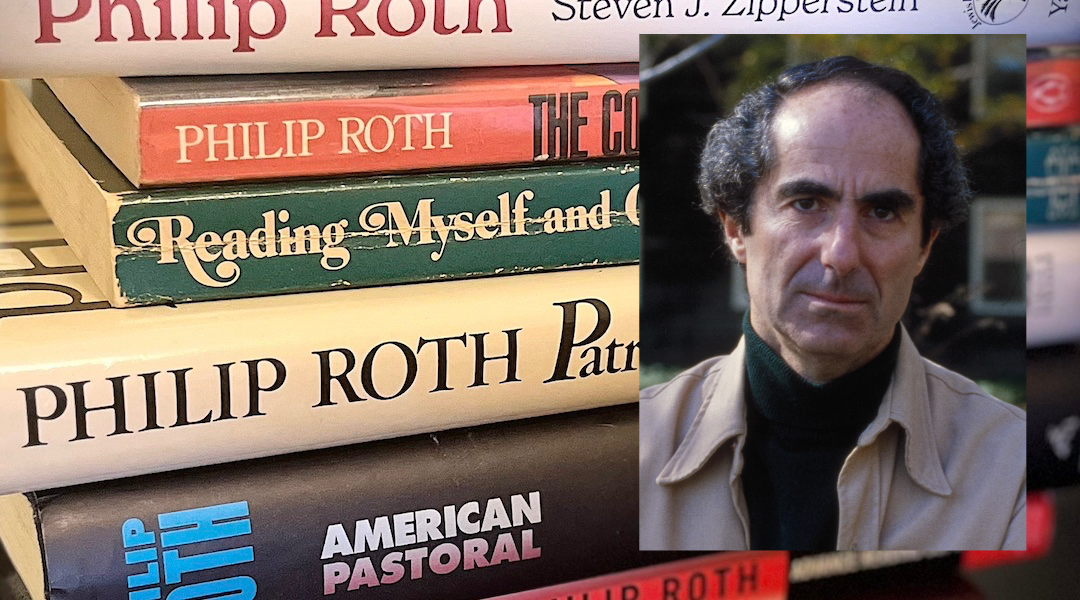

These musings were enriched by Steven J. Zipperstein’s excellent new biography, “Philip Roth: Stung by Life,” published in Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives series. I grabbed it at my favorite Manhattan bookshop before returning to Jerusalem last week and devoured it over Shabbat, even skipping synagogue and an invitation to a meal so I could tear through its nearly 300 delicious pages.

It’s a bit embarrassing to admit that Philip Roth is the writer, man and Jew who has shaped me as much as any teacher. Respected feminist writers and thinkers — from Nicole Krauss and Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi to Claudia Roth Pierpont (unrelated to Philip Roth, though a close friend) — have spoken of his greatness not only as a writer in a general sense, but as a writer who loved writing about women, and often did so exceedingly well. Yet Roth remains, in many circles, a predator at worst or a misogynist at best.

I was raised a feminist and am the father of three liberated daughters and an equally liberated son. I do not want to be on the wrong side of history in matters of misogyny or sexism. But I have come to accept that great artists like Philip Roth often wrestle with personal and creative conflict — even malevolence — when it comes to sex and love. Certain acts are unforgivable, demanding exposure and accountability regardless of a creator’s brilliance. But in the day-to-day negotiations and love songs (and novels) of intimacy, if any of us knew what we were doing while we were doing it, metabolizing those moments into art would be far less interesting, and far less necessary.

Accepting a mentor’s imperfections is akin to accepting our own. Personally, I’m sticking with Philip Roth’s imperfections in life because his cataloguing of them in fiction has helped me confront my own.

Zipperstein spoke with (JR) recently about the Roth biography, explaining why one of our most readable Jewish historians took on one of our most controversial Jewish writers. Yes, the age of the Great American (Jewish) Novel was all too male, too white and too limited by today’s standards of diversity. But Zipperstein and I both know that Philip Roth, who died in 2018, remains a historic figure — a linchpin and lightning rod of the Jewish-American zeitgeist like no one else of his era.

He emerged from the close-knit, quasi-suburban shtetl of Newark hungry for a fully American life, from baseball to the fame and fortune the Golden Land offers to its winners. He was a prophetic witness to the obsessions and obstacles of the sexual revolution; a piercing caller-out of cultural and political BS; a singular early warning system for antisemitism, from his earliest stories through the dystopian “The Plot Against America” (2004), which could easily blend figures like Peter Beinart, Tucker Carlson and Donald Trump into its fabric. He was a lover and critic of Israel who once shook Ben-Gurion’s hand, documenting the Jewish state’s triumphs and foibles. And above all, he was a writer’s writer, believing that chasing the great white whale of the Great American Novel every day until he retired in 2012 was worth the Ahabian effort.

Philip Roth receives an honorary doctorate at the Jewish Theological Seminary’s commencement in New York on May 22, 2014. (Ellen Dubin Photography)

I share many of Roth’s passions, but the most concrete thing we share — surprisingly — is an alma mater: the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

By the time Roth received his honorary degree in 2014, I had already earned my doctorate after years wrestling with ancient texts in Jewish languages Roth would not have touched. He earned his by birthing a singular Jewish voice out of modern fiction.

That he would be honored by an institution training rabbis, cantors, scholars and educators was nothing less than a Rothian (or, he might say, Kafkaesque) twist. Much of his Jewish self-perception was shaped by a darkly humorous misunderstanding, fueled — as Zipperstein details — by Roth’s false memory of being scorned and abused at a 1962 Yeshiva University event. Recordings show he was received as a hero. The dichotomy between his memory and reality reveals a primal conflict about Jewish outsiderhood that Roth carried as both a badge and a burden.

Regarding religion, Roth never equivocated. Religion, he insisted, was for dummies. Yet in my own search for a bridge between the literature and music that shaped me and my love of Jewish text and tradition, I published an essay in Zeek in 2006 arguing that Roth possessed something resembling a spiritual sensibility.

Reading Zipperstein last week, I found myself wishing I had failed a doctoral exam or two or delayed my dissertation long enough to attend that graduation ceremony in 2014.

“The first time I’ve been applauded by Jews since my bar mitzvah,” Roth said in his acceptance speech. The applause he heard — and clearly enjoyed — was richly deserved for a man who spent more than half a century enlightening, challenging, disturbing, titillating and cracking us up, even as he held up a mirror to the Jewish people’s most compelling aspirations, falsehoods, loves and honor.

Had I met Philip Roth afterward — each of us in a black graduation gown, the braided strings of our mortarboards dangling between us like two you-know-what’s — I would have thanked him for teaching me what it means to be a Jewish son, partner and man.

I felt that gratitude while reading Zipperstein, and when I lost my dad and reread how Roth lost his. I felt it again when I remembered seeing Roth on that corner by Central Park. There he was, framed in my taxi window, trying to hash it out with his person just as I had done so many times in the very same part of town. I can still imagine him walking back to his apartment on West 79th Street, anguished and disbelieving, sitting down at his computer, and — for the rest of that day and the rest of the day after and then the day after — giving everything he had to making sense of feelings that were too big to carry, so he sweated and strained and imagined them into books to explain them to all of us.

“That’s what I want to do too, Dr. Roth,” I would say. Then I would thank him for instilling in me such a crazy, often thankless desire to be a man who writes. And since it’s my fantasy, I can imagine his reply: A glint in his eye, slipping into a Viennese accent like Dr. Spielvogel in “Portnoy’s Complaint,” the book that nailed the Jewish and erotic longings of 1969, the year I was born, he would say:

“So now vee may perhaps begin. Yes?”

“Yes, Doctor,” I would reply with a glint in my eye too. And then I would walk back to my own apartment and keep writing.

is a writer and the author of “Man and God and Law: The Spiritual Wisdom of Bob Dylan.” He is CEO of the Fuchsberg Jerusalem Center.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of (JR) or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.