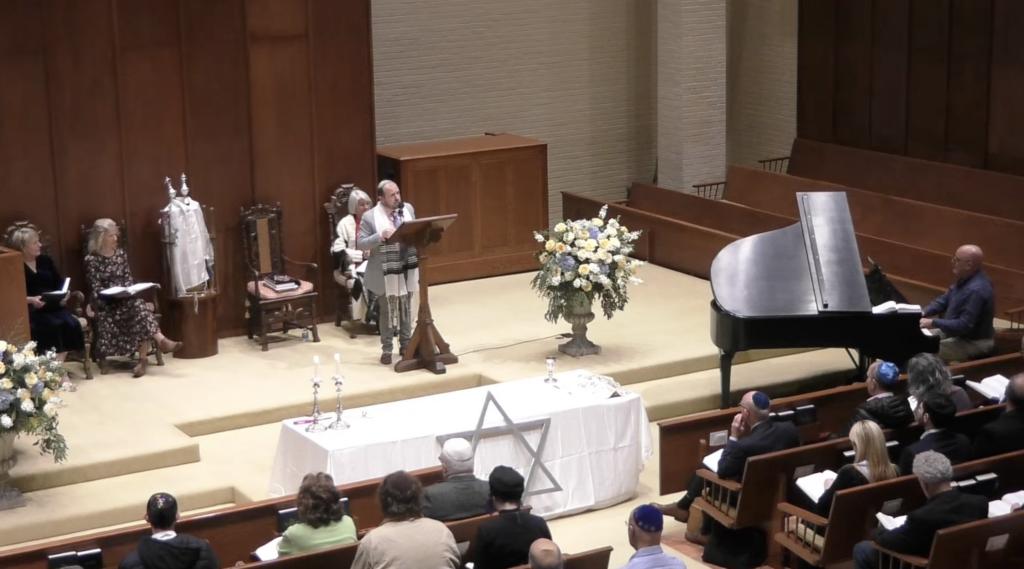

JACKSON, Mississippi — The emotion was palpable in the pews Friday night at Beth Israel Congregation’s first Shabbat service since its synagogue was targeted by an arsonist last week.

“We will not only survive, we will thrive,” the congregation’s student rabbi and spiritual leader, Benjamin Russell, told his community. He was draped in the only surviving tallit from the synagogue’s library, where the arsonist lit the fire.

“A few days ago, someone tried to wound us, someone tried to destroy what we love, someone tried to tell us that we do not belong in our own city, that being visibly Jewish is dangerous, that being proudly Jewish is a risk, that being a synagogue is an invitation for hatred,” Russell said. “What they failed to understand is that we are not made of wood and paper and shelves. We are made of Torah, memory, community, stubborn love and 3000 years of defiance.”

Roughly 170 Beth Israel congregants filled Northminster Baptist Church in Jackson on Friday night, after the church lent its space to the displaced community.

Founded in 1860, Beth Israel has always been the only synagogue in Mississippi’s capital. The arson attack last week, which burnt out the synagogue’s library and destroyed two of its Torahs, was not the first time that Beth Israel’s congregants were faced with the task of rebuilding. In 1967, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the synagogue, and, months later, also targeted the home of Rabbi Perry Nussbaum after he advocated for civil rights and desegregation.

Beth Israel Congregation in Jackson, Mississippi, on Jan. 16, 2026. (Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

Reflecting on the congregation’s 160-year-old roots in Jackson, Russell said, “We have prayed through wars, depressions, pandemics, demographic shifts and antisemitism in every decade, and every single time we did more than survive, we adapted, we rebuilt, we showed up, and that is exactly what we are doing and will continue to do now.”

Throughout the service, little mention was made of the suspect who confessed to the arson, Stephen Spencer Pittman, a 19-year-old resident of a suburb of Jackson who told the FBI that he had targeted Beth Israel because it was a “synagogue of Satan.”

Standing outside of the charred entrance to the synagogue earlier in the day Friday, Abram Orlansky, a lifelong Jackson resident and past president of Beth Israel Congregation, said that most of the conversations within the congregation had not revolved around Pittman.

“To the extent we’re talking about him, we’re just saying what he wanted to do was interrupt or destroy Jewish life in Jackson, and all he’s going to succeed at is making it more vibrant,” said Orlansky. “All he’s done is reaffirm the connection between this Jewish community and this city.”

Beth Israel Congregation’s president, Zach Shemper, and student rabbi, Benjamin Russell outside of the synagogue building on Jan. 16, 2026. (Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

On Thursday, a host of Christian faith leaders and Jackson city officials said a prayer for the congregation during a citywide prayer service. Zach Shemper, the president of Beth Israel Congregation, said more than 10 churches had offered to host the synagogue for Shabbat.

“We’ve been persecuted for thousands of years, and just like we survived that, we will survive this,” said Shemper outside of the synagogue. “All this atrocity did was relocate where we’re having services.”

Support from other Jewish congregations across the South was also visible throughout the services.

Temple B’Nai Israel, a Reform synagogue in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, lent the community a Torah as well as 50 prayer books. A synagogue in Memphis, Tennessee, sent another 100 prayer books.

The oneg after services was provided by Touro Synagogue in New Orleans, Louisiana, and included a pecan praline challah king cake, a Jewish twist on the traditional Mardi Gras dessert.

The challah king cake loomed large over the evening. When Shemper announced the pastry at the end of the service, several children in the audience cheered and audience members applauded.

On Friday morning, Orlansky showed a photo of the cake on his phone and said, “That’s Jewish southern culture,” adding that there is a store in New Orleans called “Kosher Cajun.”

The pecan praline challah king cake at the Beth Israel Congregation’s oneg on Jan. 16, 2026. (Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

In Jackson, a city with no explicitly Jewish establishments or cultural centers, Beth Israel has acted as a central hub of Jewish communal life. (The city’s only Jewish restaurant, Olde-Tyme Deli, closed in 2000 after serving the Jewish community for 39 years.)

“We are the minority in the area, and so we don’t have all of the Jewish delis and JCC down the road and all of those things,” Russell said. “Our synagogue is that place for us to meet.”

About a 45 minute drive from the synagogue is Jacobs Camp, a Jewish summer camp run by the Union of Reform Judaism.

Sarah Thomas, the synagogue’s first vice president, read an address by Rabbi Rick Jacobs, the URJ’s president, aloud during the service.

“Beth Israel family, like our ancestors, who endured the plague of hate and still found light, we think of all of you and know that there’s much light in your midst,” Jacobs said in the comments. “We pray that you continue to bask in the light of community and the light of solidarity and the light of hope for better days ahead.”

In the absence of Jewish infrastructure in Jackson, Russell said the congregants “make every space that we are in Jewish by our own presence there.”

According to Russell, some of the local spots that have become surrogate Jewish spaces include Myrtle Farms, a brewery, and Thai Tasty, a restaurant a short walk from Beth Israel.

Russell said that Thai Tasty had become so popular with his congregants that he now announces during services when its owners make their annual monthlong trip to Thailand.

“Something that we see across the South’s Jewish communities is that there is a level of pride, because you may be the only Jewish person in your high school,” said Russell. “I think there’s just a little bit of charm in that resilience or that stubbornness that we have that says we’re going to be here, we’re going to always be here.”

In high school, Orlansky recalled, there were two other Jewish students in his grade. Today, he said his two children are the “only Jewish kid in their class, or either class on either side of them.” That makes Beth Israel a haven, he said.

“A shared experience I have with my kids is being able to come to this building and not be the sort of constant representative of the Jewish people to everyone you know,” said Orlansky.

Rachel Myers and Abram Orlansky pose on Beth Israel Congregation’s bimah on Jan. 16, 2026. (Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

Orlansky said that the responsibility of representing the Jewish community was both an “honor” and a “challenge.”

“It is an honor to live in a place like this where people ask you about your religion, and people kind of look to you for answers about Judaism, but it can be a challenge, and so having a home where everyone around you is also Jewish is a respite,” he said.

Thomas, who is also a lifelong Beth Israel congregant, said growing up she was also the only Jewish student in her grade, but when she came to Beth Israel Congregation on Wednesdays and Sundays she found a “safe space.”

“We talked about things that were happening outside of here and, and how we were going to respond with our Jewishness to a world, or a community, that was just different, and we knew that here was our safe space,” said Thomas.

Thomas said the Beth Israel building was an “epicenter of life” for the community’s 140 families.

“What I want people to know about the southern Jewish communities, especially the smaller ones, or the only ones within a 90 mile radius, is everything related to Jewish life happens here,” said Thomas.

The library inside Beth Israel Congregation on Jan. 16, 2026. (Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

But while the building had served as a focal point of the community, Thomas added that “the building is not what makes up our community.”

“The building is not what makes up our community, our community is made up of the people,” said Thomas. “We’re going to be in other places, and we’ll make that our home, but really together, we the people are going to be home to one another.”

Shari Rabin, an associate professor of Jewish studies and religion at Oberlin College and the author of the 2025 book “The Jewish South: An American History,” told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that the sentiment was common in small Jewish communities in the region.

“Synagogues are such important institutions in these smaller Southern communities,” said Rabin. “This is the center of Jewish life, and it’s really important for Jewish communities there to have a public address to show we’re here, we’re part of the landscape, other Jews can find us here.”

But Rabin said that public visibility also has a potential dark side.

“It can also make these institutions a target for those who are poisoned by various ideologies and decide that they want to make Jews a target,” said Rabin.

Following the attack last Saturday, most of the synagogue’s leaders said they had initially assumed the fire had been caused by an electrical malfunction or another accident.

While antisemitism has risen across the country, in many Southern states, including Mississippi, the trend has felt less pervasive. From 2022 to 2024, the number of antisemitic incidents in the state rose from 7 to 20, according to the Anti-Defamation League’s annual antisemitism audit.

“To know that someone could do this in your own community is frightening, but it’s also eye-opening,” said Russell. “We always say, not me, not me, not me, not us, not our community, and I think what I have learned, and my message for everyone, is that you never know.”

The day after the arson attack, Rachel Myers, the second vice president and co-director of the religious school at Beth Israel, hosted the synagogue’s Sunday school at the Mississippi Children’s Museum, where she works as the director of exhibits.

There, Myers showed the class of 14 children a slideshow of the damage inside the synagogue and helped them brainstorm ways to rebuild it. She said one child imagined a cotton candy machine while another said, Llet’s do a mural of all the rabbis on the wall.”

Smoke damage inside a classroom in Beth Israel Congregation on Jan. 16, 2025. (Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

“I just was trying to focus on: this thing happened to us, all of these grown-ups around you are the ones that work so hard to make Jewish life happen, and we’re going to continue to make Jewish life happen,” said Myers.

For the teens in the synagogue, Myers said the main question that was asked was “why.”

While Myers said she hadn’t yet planned her lesson for the teens, she said she would lead with explaining that “when people are bad and angry, they look for somebody to blame, and in this case, this young person decided to blame Jewish people.”

After being a part of the congregation for almost 20 years, Myers said she had never before experienced antisemitism in Jackson.

“I think I know that there’s a rise of antisemitism, and I think I know that there’s a rise of mis- and disinformation on the internet,” said Myers. “I know there’s crazies on the internet, I don’t read the comments, but the fact that someone, that crazy, left the internet and came and did a physical act of harm to us — it is surprising.”

Russell said that he was concerned for the teens of Jackson.

“I think the biggest thing is we have to watch our kids and our teens, the fact that they’re being radicalized so quickly online by social media and other things on the internet,” said Russell, later adding, “Of course, we have to monitor, but the real antidote is just to stop breathe and love each other, even when we disagree.”

Benjamin Russell speaks with congregants at the Northminster Baptist Church on Jan. 16, 2026. (Jewish Telegraphic Agency)

As the congregation mingled over the challah king cake following the service, Joshua Wiener, a Beth Israel Congregation member since 1981, said he believed that Russell and Shemper had represented the community well.

“As [Russell] said, antisemitism has been around since even before Pharaoh, but it hasn’t touched us here, and so I think there’s just shock at what happened, maybe a little relief that it wasn’t worse, and maybe some relief that it was not an organized effort,” Wiener said.

He described Jackson’s Jewish population as a “drop in the bucket,” but said they had always had an “outsize presence and influence, and a lot of that is just because of how welcomed we have been in the community.”

At the end of his sermon, Russell offered an instruction to the worshippers, several of whom were visibly emotional.

“This is the time to say, out loud, I am Jewish, I am proud, this is my community, and I belong here,” he said.

“I want to say something clearly. Beth Israel is still here, Jewish life in Jackson is still here, and we are not going anywhere, because the opposite of fear is not bravery, it is presence,” Russell continued. “Every time we gather, every time we pray, every time we teach a child to read aleph bet, every time we put on a tallis, every time we celebrate a bat mitzvah or mourn with the family, we are safe. We belong, we matter, we will outlive every Pharaoh history produces.”