Photo Credit: Wikimedia, Jonathan Rashad

{Originally posted to the JCPA website}

The Disintegration of the Middle East Nation-States

In a few weeks, the so-called “Arab Spring” will be entering its tenth year, bringing with it a factionalized Middle East, a polarization of religious hatred between Shi’ites and Sunnis, and the tightening grip of Iran in the Arab Middle East. Today, the Middle East is a combination of confused Arab nation-states that have shown their weakness and incapacity to contain the Iranian threat. The never-ending instability of Arab regimes that extends from west to east and from north to south creates the vacuum that allows the formation and violent presence of sectarian, radical, and extremist Islamic militias that threaten the Middle Eastern and world order.

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 0 });

The disintegration of the Middle East nation-states, which were the focus of all major events in the last decade, plus the emergence of different regimes in most Arab countries, have placed the issue of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on hold. In spite of several military clashes between Israel and Hamas, the Palestinian issue was not on the agenda of the Arab world. In fact, the Palestinian issue was marginalized and frozen into a holding position, waiting for better days to come and a deus ex-machina. Instead, the present U.S. administration is planning a solution called the “Deal of the Century,” which is yet to be presented to the parties. At this point, the “deal” stands no chance of being accepted by the Palestinians and probably by most of the Arab world, since they have expressed their opposition to the recognition of Jerusalem by the United States as the capital of Israel and the U.S. acknowledgment that the Israeli settlements in Judea and Samaria do not infringe on international law.

The Rise of Hizbullah

In profound contrast, Hizbullah, a marginal militia created by Iran in 1982, became the flagpole to rally around. Hizbullah transformed into “the” powerful proxy, from a so-called “Lebanese liberation movement” fighting Israel’s military presence in Lebanon into a mercenary force at the service of Iran. Hizbullah contributed to saving Bashar Assad’s regime and became a powerful militia that has, in turn, trained other Iranian proxies (inter alia – in Yemen, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan). Hizbullah has become a crucial destabilizing factor meant to topple traditional Arab regimes and put in its place regimes that will be favorable and obedient servants to the Supreme Leader in Iran.

Hizbullah, taking advantage of its reputation in Lebanon as the preeminent fighting force against Israel, who forced Israel to withdraw from Lebanon in the year 2000 and scored a “victory “ in the 2006 Lebanese War, advanced by signing an alliance with the Maronite leader Michel Aoun (then in the opposition) in 2006. This created a situation in which Hizbullah controls the main levers of power in Lebanon to such an extent that it blocked the election of a president for almost two years until it succeeded to crown its candidate, Michel Aoun, as president of Lebanon. Lately, Iran is trying to impose a candidate for the premiership following the protests in Lebanon that were meant to reform the Lebanese regime. Hizbullah’s intervention in Syria to save the Assad regime at the orders of Tehran, as well as its involvement in terrorist activities in various parts of the Arab world, have caused a negative reaction in Lebanon, where Hizbullah today is wholly identified as the agent of an Iran-dominated Lebanon. Hizbullah is openly criticized and accused of corruption and endangering the Lebanese state because of its warmongering against Israel, even though Hizbullah is very much feared since it is the only real power on the ground.

Iran Is Involved in Every Conflict

In this past decade, Iran has emerged as a regional power involved in every conflict in the Arab Middle East. This game-changer results from the projection of Iranian military power directly and through its proxies throughout different countries. Were it not for the Iranian regime, with the help of its proxies and subsequently Russia’s military intervention, Bashar Assad’s regime would have likely collapsed under the pressure of the jihadist advance.

Iran took advantage of its privileged position in Syria to push forward its anti-Israeli agenda by heavily arming Hizbullah in Lebanon for confronting Israel and by deploying Iranians and its proxy legions in Syria and bordering Iraq. Iran did not limit itself to the heart of the Middle East but consolidated its grip on the Iraqi regime while adventuring forward in a show of force in the Persian Gulf and taking aim at the Saudi regime caught in a never-ending war against the Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen. The withdrawal of the United States from the Iranian nuclear deal and the adoption of sanctions against the Iranian regime catalyzed overt and covert Iranian subversive activities. It emboldened Iran to launch attacks directly and indirectly through its Houthi proxies against targets deep inside Saudi territory, maritime targets in or near the Persian Gulf, as well as trying to hit Israeli territory from Syria, using Iraqi-based proxy forces.

The Rise of Radical Islam

The decade also witnessed the emergence of ISIS and its military defeat, the spawning of a plethora of radical Muslim terrorist organizations, which swept the area from Morocco to Bangladesh, Africa, China, and Southeast Asia. A violent and unseen wave of cruelty initiated by these radical Sunni movements drowned the Middle East, China, Southeast Asia, and Europe in a blood bath. This seems to have been the result of Sunni frustration stemming from the hostility nurtured against American military intervention in places such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

This was the decade in which radical Islam recruited thousands of European and Asian Muslims to the fighting ranks of ISIS. ISIS and other radical jihadist movements flocked to Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and Libya to re-establish the Muslim Caliphate and dominate the world. Radical Islam spread as an extremely contagious virus and found converts throughout the world. Most alarming was the rally of European volunteers and their identification with the pan-Islamic worldview, which replaced their national pride. Even though ISIS was defeated on the ground and its leader was killed, ISIS has survived and is flourishing in the Sahel region of Africa and is still present in Syria and Iraq and in dormant and active cells throughout Europe, South America, and the United States.

Turkey’s Muslim Brotherhood Leader

Parallel to the ascendance of Iran, another regional power has emerged, fulfilling a major role in the Middle East. Turkey, with its Muslim Brotherhood leader, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has adopted an unprecedented activist and aggressive policy. Turkey has pursued a specific agenda that has brought it into open conflict with most Arab states, its allies in NATO, and the United States.

Turkey invaded Syrian and Iraqi territories and has no intention whatsoever to retreat. On the contrary, it has embarked lately on a policy of repatriating the three million Syrian refugees that Turkey allowed to enter its territory since the beginning of the civil war in Syria, into an area adjacent to its southern borders that was predominantly Kurdish. Thus, Turkey is initiating a process of ethnic cleansing, a process much feared by the Kurds, which will create a new ethnic partition of Syrian territory at the end of the day. Turkey was deeply involved in facilitating the introduction of ISIS fighters from Europe and Asia into Syria and Iraq. Turkey’s intelligence services were also implicated in the supply and training of jihadists in Egypt and Libya. Turkey has signed a defense treaty with Qatar, according to which a garrison of 4,000 Turkish military personnel serves as a buffer and protector against Saudi incursions. Turkey also has a military base in Somalia and obtained from the al-Bashir regime in Sudan full access and control of Suakin Island, which once hosted the headquarters of the Ottoman fleet in the Red Sea.

Turkey’s intelligence agents were caught red-handed in Sinai fighting alongside jihadist organizations against the el-Sisi regime. Today, Turkey is fully involved in the fighting in Libya, siding with the Tripoli Government of National Union against the Saudi-Emirati-Egyptian-French-Italian-backed Field Marshall Khalifa Haftar. Turkey is ready, according to press reports, to send its own troops into battle against the Benghazi forces led by former CIA agent Haftar.

Turkish drones are now flying in Libya, reportedly piloted by Turkish intelligence operatives.

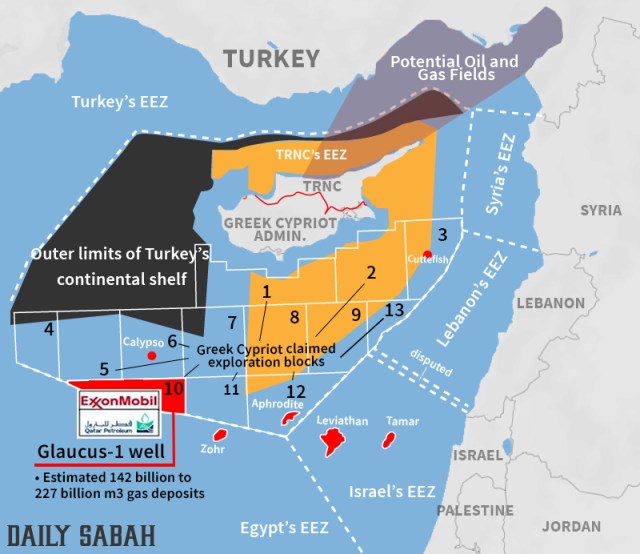

Turkey continued aggravating its Mediterranean neighbors by signing in December an agreement with the Tripoli government in Libya, which allows Ankara to extend its maritime EEZ (exclusive economic zone) well beyond the internationally agreed 200 nautical miles, thus infringing on the EEZ rights of Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, and Israel. Against all international maritime laws, Turkey has initiated exploration and drilling for gas in the northern part of the Mediterranean Sea adjacent to Turkish-occupied Northern Cyprus. To make clear it has no intention to rescind, Turkey flew in armed drones that landed in airstrips in occupied-Northern Cyprus and put its maritime force on alert, ready to intervene if Turkey’s “interests” are endangered. Finally, Turkey has engaged in a sort of brinksmanship vis-a-vis the United States by provoking President Donald Trump’s ire following its decision to purchase the S-400 Russian air defense system and a natural gas pipeline.

The Trump administration retaliated in the past by imposing sanctions on Turkey, following its arrest of American pastor Andrew Brunson, and again after the signing of the Russian S-400 deal, removing Turkey from the U.S. F-35 stealth fighter project. In return, Turkey threatened to end the U.S. military presence at the Incirlik and Izmir airbases. Then, Turkey subtly threatened its European allies, saying that Turkey will not hesitate to repatriate to their original countries those ISIS fighters kept in the Turkish jails. Turkey would also allow thousands of Syrian refugees dwelling inside Turkey’s territory to migrate to European destinations. On the other hand, Turkey’s relations with Russia and Iran were rocky. Turkey’s air defenses shot down a Russian aircraft in November 2015, an event that strained relations for quite some time between Moscow and Ankara. Even though the two overcame the tensions then and adopted a businesslike attitude, Turkey today is objecting to the Russian/Syrian bombardment of the Syrian rebel stronghold in Idlib, where Turkey maintains 12 observation posts.

Finally, one cannot underestimate the hostility the Turkish regime feels against Israel, especially since the 2010 Gaza flotilla incident. The once-flourishing relations soured to a point where Turkey serves today as a refuge for Hamas and Islamic Jihad leaders, who enjoy Turkish financing. According to press reports, Turkey allows Hamas to prepare and initiate terrorist operations against Israeli targets in Israel and abroad from Turkish soil. Meanwhile, Turkey has increased its anti-Israel campaign over Israel’s sovereignty over Jerusalem.

The Reappearance of Russia as a Superpower in the Middle East

This past decade saw the reappearance of Russia as a superpower in the Middle East. A stuttering and hesitant American policy, the loss of interest by Washington in Arab affairs, the rapprochement with Iran initiated by the Obama Administration, and declarations about withdrawal of U.S. forces from areas of conflict in the Middle East, such as the Kurdish areas adjacent to the Syrian-Turkish border, have all allowed Moscow to fill every vacuum and to replace the United States politically with new arms and economic deals.

As a result of its massive military presence in Syria, Moscow became the mediator Israel could not circumvent and a force on the ground with whom Israel had to coordinate deconfliction arrangements to prevent unwanted clashes between the militaries of both countries. As a result of the contact between Israel and Russia relating to the Syrian conflict and specifically with regard to the Iranian presence in Syria, Moscow assured Israel it had reached an agreement with Iran to keep its proxy forces a distance from Israel. Russia claimed Iranian proxies would deploy 80 kilometers east of the Golan Heights, an arrangement that Hizbullah and Iranian advisers and intelligence units did not observe from Day One.

However, Iranian influence in Syria is still an issue. Moscow is not comfortable with Iranian influence since Iran has succeeded in securing exclusive economic rights related to reconstruction projects in Syria in the post-civil war era that Russia sought. In fact, both Russia and Iran are at odds in the Syrian context, since each has their own agenda that does not comply with the ultimate goals of the other party. One thing is certain, both Iran and Russia will watch Turkey’s next steps carefully, since it will directly influence the future resolution of the civil war in Syria.

The Decline of U.S. Influence

As observed earlier, this decade witnessed the decline of U.S. influence because of its diminishing interest in the region. America’s traditional allies understood very quickly the direction the wind was blowing and tried to find alternatives, mainly by turning to Russia and forming local and regional alliances. Even though the United States intervened militarily in the Syrian conflict, the intervention was sporadic and did not change the facts on the ground. Obama’s famous “Red Line” was crossed several times by Syria during the new U.S. presidency, and the Trump administration did not initiate any major change towards the Syrian crisis. The United States chose to concentrate on its traditional Arab allies (mainly Saudi Arabia) for economic deals in exchange for military support, while its main effort was focused on the “Deal of the Century” meant to reach peace between Palestinians and Israelis. However, instead of closing the gap between the parties, a series of American decisions widened the fracture between Israel and its neighbors. American actions included recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Israel, acceptance of the annexation of the Golan as Israeli territory, and recognition that Israeli settlements in Judea and Samaria do not infringe on international law. These decisions stiffened the Palestinians’ rejectionist attitude and deepened their refusal to consider the United States as the traditional “honest broker.” The Palestinian leadership believes that the United States is making it more difficult to bridge the gaps between Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

The main issue on the agendas of both Obama and Trump’s administrations was Iran. While Obama was following an appeasement policy towards Teheran, Trump chose confrontation as a policy, after having announced the U.S. withdrawal from the flawed nuclear deal with Iran. The United States decided to curb the Iranian regime through harsh economic sanctions and refrained from crossing the threshold of military confrontation.

Several incidents of Iran’s direct and covert actions were met with restraint and tolerance. The United States preferred to continue the sanctions regime rather than answering in kind for the bombing of Saudi oil installations, the downing of American drones, and the sabotage of oil tankers. President Trump himself admitted that he had stopped a military reprisal ten minutes before the mission was to be carried out against Iranian targets because he was told it could have caused the deaths of 150 people. The hesitation was similar to Obama in the Syrian poison gas case, when, after strolling in the White House gardens, he decided not to launch a devastating attack on Syrian targets following the use of chemical weapons against the Syrian population. This is exactly the point where U.S. allies in the area realized that they could not count on U.S. military intervention in case they were threatened by an outside danger, and they began to look for alternatives.

The Arab Spring Left a Wake of Destruction

Arab regimes continued their show of weakness and their need to adjust to a new reality. Except for Morocco, Jordan and the Gulf states, all other Arab countries witnessed the disappearance of the old guard and its replacement by a new team. Wheelchair-bound President Abdelaziz Bouteflika of Algeria quit, leaving a country in an internal struggle that vacillated between civil disobedience and radical regime change. After the midnight flight of Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisia suffered from continuous terrorist attacks by jihadists and two presidential changes. Finally, a moderate Islamic regime emerged, far from the secular regime established by the founder of independent Tunisia, Habib Bourguiba.

After the fall of dictator Muammar Qaddafi, Libya became a failed state divided between two governments and at the mercy of jihadists who dominate the major part of the south of the country. Egypt experienced a Muslim Brotherhood takeover for almost a year before the military returned to power. Six years after the takeover, the Egyptian military regime is still fighting to stabilize the country attacked by jihadists and the Muslim Brotherhood. In Sinai, Egypt battles elusive ISIS fighters. In Sudan, Omar Al-Bashir, who ruled the country for 30 years, was toppled by his army, and a shaky regime of civilians controlled by the military has taken over the country.

Syria is still in the midst of a brutal civil war with its population decimated and displaced, its infrastructure destroyed, and almost six million refugees currently outside of its borders. Iraq is in turmoil and is virtually in a state of civil war, torn between two main factions – the pro-Iranian one and the local Iraqi population who often split along Sunni-Shia lines. Saudi Arabia is ruled de facto by Crown Prince Mohammad Ben Sultan (known as MBS), yet the ruler’s son is deeply stuck in the Yemenite mud, unable to put an end to an armed conflict, and deserted by its former allies (Senegal, Egypt, the Emirates, and Sudan). Yemen has been the scene of a bloody takeover by the Houthis, a pro-Iranian Shiite minority, and has been sucked into a deadly whirlpool of civil war. Its former president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, was assassinated in a chaotic Houthi attack.

Even states like Jordan and Morocco, that did not witness a change in their regime, are struggling against internal destabilization and terrorist forces. Lebanon is the last to join the cycle of instability and fractured government; the country entered into a constitutional deadlock in October 2019. Lebanese protesters demand radical economic reform, a change in the sectarian regime, and a replacement of the old government with a radically new form of rule. They seek a new government which would be clean of corruption, and far from the unwritten covenant of 1943, which distributed the central positions in the state according to a religious sectarian formula.

Oddly enough, so far, the Palestinian Authority was spared from the Arab virus of instability, even though octogenarian Chairman Mahmoud Abbas’ authority is continuously challenged by Hamas. While the aging and ailing Palestinian leader succeeded (with the active assistance of Israel) in containing Hamas from taking over Judea and Samaria (the West Bank), the PA did not achieve any progress in the process of “taming” Hamas or the formation of a united Palestinian leadership. On the other hand, Hamas consolidated its grip on the Gaza Strip and has been busy fomenting subversive activities in Judea and Samaria. Strengthened by its military confrontation with a hesitant Israel and aware of the Israeli threat that it will wage an all-out war against it, Hamas finally chose a more conciliatory attitude towards Israel and has been discussing the terms of a prolonged truce to concentrate on the economic plight that cripples its population. No doubt the next decade will witness the demise of President Mahmoud Abbas, opening the scene for a struggle between his potential heirs and a showdown between the Palestinian Authority and Hamas.

The Ignored Water-Related Threats

Most illustrative of the weakness of the Arab regimes was their inability to deal with existential dangers: Egypt and Iraq were so busy with their domestic instability, they could not react in time to daring water projects initiated by their neighbors aimed at redirecting the flow of rivers to create energy and develop their own agricultural projects.

Ethiopia is building a mammoth dam on the Blue Nile called the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), whose planned inauguration is scheduled for 2022. It is the biggest hydroelectric power facility in Africa and seventh-largest in the world. The massive dam is being built 20 km. from the Sudanese-Ethiopian border on the Blue Nile, which provides 85 percent of the water flow to Egypt downstream (the White Nile provides 15 percent), and has six times the output of energy of Egypt’s Aswan Dam. This is the equivalent of six 1000-megawatt nuclear power plants.

The dam could create a water shortage that has never existed in the 7,000 years of Egyptian history. Egypt argues that each loss of two percent of its water share would provoke the desertification of almost 80,000 hectares. Finally, with the beginning of the filling of the reservoir, the Aswan Dam water level would probably drop in the best-case scenario to 170 meters (eight meters less than today), and in a worst-case scenario, the level would drop to 168 meters, almost enough to jeopardize the production of electricity by the dam’s turbines. There is little wonder that Egypt has several times contemplated the possibility of waging military action against the Ethiopian dam.

In Iraq, little attention has been given to the brewing humanitarian crisis over the Tigris (Dajla in Arabic) and Euphrates (Furat in Arabic) rivers, both iconic rivers on which Iraq’s existence in both ancient and modern times has always depended. According to Iraqi sources, at least 42 rivers and springs of water from Iran have been diverted by the Iranians, causing a migration of Iraqis from the water-stricken areas. The Turks, for their part, have built five big dams on the Tigris and several minor ones (part of a grand design to construct a total of 22 dams – 14 on the Euphrates and eight on the Tigris) with the Ilisu Dam being the biggest with a reservoir of 300 square kilometers!

As a result of the Turkish and Iranian water projects, Iraq has found itself having lost more than 50 percent of its water, which means that nearly 3 to 4 million square miles of agricultural land will turn to desert.

Moreover, before the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iraq used to generate power from 12 hydroelectric stations. Reduced water flow because of Turkey and Iran, coupled with the drought and the war with the Islamic State, have left Iraq’s major cities with an intermittent supply of electricity (two hours on and two hours off). While the Turks seem inclined to sympathize with the Iraqis and have slowed the pace of filling the reservoir of the Ilisu Dam on the Tigris, the Iranians have shown no compassion at all. Iran may even have an interest in creating a crisis in Iraq to put pressure on Iraqi politicians to align themselves with Tehran’s political agenda. Only with Iraq ensnared in the Iranian sphere might Iran be amenable to compromise on the water distribution between the two countries.

Iran’s Proxies Are Challenging Israel’s Military Superiority

In another development, the Middle East saw a definite shift in the qualitative arms race between Israel and its adversaries. Having learned the lessons of the Israeli-Palestinian-Lebanese armed conflicts, the first Gulf War, and the Iraqi-Iranian eight-year military confrontation, Iran’s proxies Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and Hizbullah are challenging Israel’s military superiority. Israel was challenged with weapons that were meant to counter its military might: ground-to-ground missiles, unmanned armed drones, and long-range cruise missiles. With Iran’s assistance, Israel’s enemies entered an arms race in which they stockpiled weapons that could hit Israel’s rear to terrorize its population. Israel countered by developing anti-missile systems, such as the “Iron Dome,” the “Arrow” anti-ballistic system, and “David’s Sling,” which have proven to be effective against these threats. The Iranian proxies, meanwhile, received missiles by the thousands and could fire them (as in the case of Hamas and the Islamic Jihad) by the hundreds in an effort to barrage Israel with missiles and erase its qualitative edge by firing salvos of short-, medium-, and long-range missiles.

In the context of Syria and Hizbullah, Israel embarked on a partly successful campaign, called by the Israeli military as the “battle between the wars,” meant to stop the flow of Iranian missiles to Hizbullah. Israel strove to prevent Hizbullah from acquiring precision-guided missiles capable of hitting targets with great accuracy – the ultimate goal in these attacks against Israel. The missiles, cruise missiles, and drone threats are not directed against Israel exclusively. Saudi Arabia is the prime target of long-range missiles and cruise missiles, a threat the Saudis had no answer to and illustrated more than anything their inferiority against Iranian-backed missile terrorism.

Interestingly, during this decade of turmoil, the process of normalization between Israel and some of its Arab neighbors has advanced a notch. It is particularly true in relations between Israel and the Gulf states. Delegations from Israel have been received in the Gulf States, and Israeli businessmen, as well as tourists and sports teams, are a common sight in Dubai, Bahrain, Qatar, and Morocco. Rumors have circulated about an eventual meeting between Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS) and Israeli politicians. High-ranking Saudi officials and businessmen met in the open with a Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs team headed by Jerusalem Center President Amb. Dore Gold to discuss ways of containing the Iranian threat and developing bilateral relations. A trilateral meeting even took place between Indian, Israeli, and Saudi teams in New Delhi, far from the limelight of the press. Some Arab thinkers (writers, journalists) have expressed openly the need to normalize relations with Israel, and quite surprisingly, they were not reprimanded or threatened. Even the peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan and the agreement with the Palestinian Authority – while under severe criticism from the opposition – have survived the turmoil of the Middle East upheavals.

What Are the Prospects Ahead of Us?

What will be the main issues addressed in the near future? Clearly, the Arab world will continue to struggle for stability, and in the course of this direction, new entities will replace existing ones. Change is not over. It will certainly apply to Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Algeria, Tunisia, and, of course, the future of the Palestinian Authority.

What future awaits post-civil war Syria? Every solution will have implications for all the parties involved and will weigh heavily on the stability of the region. The same applies to Iraq. Is it on the way to becoming another “province” of Iran, or will Iraq recover its ancient anti-Persian alignment? Unforeseen change of regimes in Egypt and Saudi Arabia could drag the Middle East into a new era of uncertainty and trigger tensions with Israel that could have a negative impact on its peace treaty with Egypt and Jordan alike.

Undoubtedly, the jihadist factor will continue to be present and represent a destabilizing element. However, in the battle between jihadist movements and nation-states, the Middle East has proven that the old order has prevailed in the encounter.

With this background, what will be the future of relations between Israelis and Palestinians, and to what extent – if at all – will President Trump’s “Deal of the Century” succeed to bridge the differences between the two parties and establish a mode of co-existence?

Issues of the scarcity of water will have to be addressed, and probably the solution will be found through diplomatic rather than military initiatives.

The question remains unanswered as to the United States’ future policies and if it wants to face Russian efforts to consolidate its position in the Middle East. To what extent will Turkey’s Erdogan provoke his rivals domestically and externally? Finally, just how far is Iran ready to exert itself in order to rule the Middle East?

Beyond all those potential developments, the most central issue will undoubtedly be the unavoidable confrontation between Israel and Iran and its proxies in the north and the military confrontation between Israel and Hamas in the south. The build-up is going on and most probably will reach a climax in the years to come. The potential clash between Iran and Israel – if and when it happens – will shape the next decade of the Middle East.

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 10 });