A world-first: Israeli researchers connect a real locust ear to a robot to be able to “hear”

A technological and biological development that is unprecedented in Israel and the world has been achieved at Tel Aviv University

A technological and biological development unprecedented in Israel and the world has been achieved at Tel Aviv University. For the first time, a ear of a locust was connected to a robot. The robot receives the ear’s electrical signals and responds accordingly. The result is extraordinary: Acording to the expectations, when the researchers clap once, the locust’s ear hears the sound, and the robot moves forward; when the researchers clap twice, the robot moves backward.

The researchers explain that at the beginning of the study, they sought to examine how biological systems’ advantages could be integrated into technological systems and how the senses of dead locust could be used as sensors for a robot.

“We chose the sense of hearing,” says supervisor Dr. Ben M. Maoz of the Faculty of Engineering and the Sagol School of Neuroscience, “because it can be easily compared to existing technologies. The sense of smell, for example, the challenge is much greater. Our mission was to replace the robot’s electronic microphone with an insect’s ear. We used the ear’s ability to detect the electrical signals from the environment. In our case vibrations in the air, using a special chip, convert the insect input to that of the robot.”

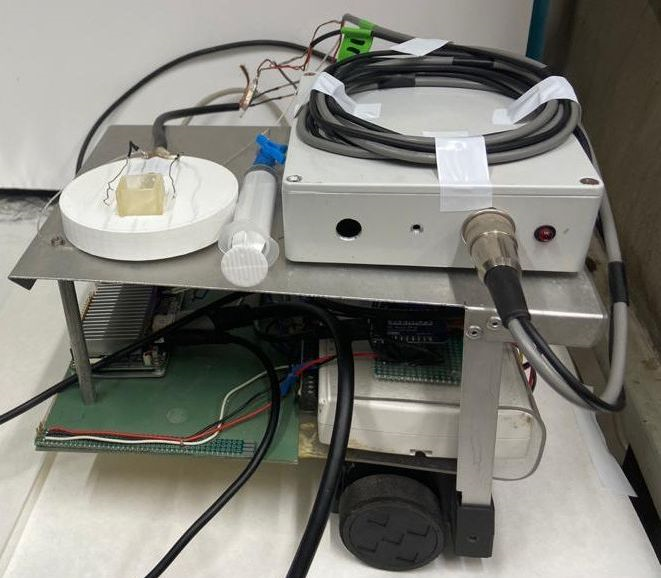

The interdisciplinary team faced several challenges with carrying out this unique and unconventional task. In the first stage, the researchers built a robot capable of responding to signals it receives from the environment. Then, in multidisciplinary collaboration, the researchers could isolate and characterize the dead locust ear and keep it alive, functional, long enough to successfully connect it to the robot. In the final stage, the researchers succeeded in finding a way to pick up the signals received by the locust’s ear in a way that the robot could use. At the end of the process, the robot could “hear” the sounds and respond accordingly.

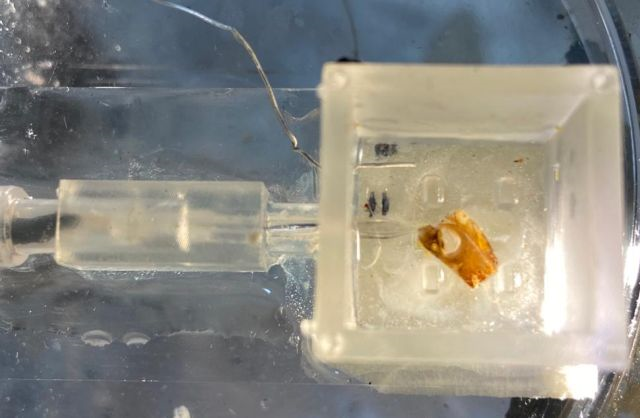

“Prof. Ayali’s laboratory has extensive experience working with locusts, and they have developed the skills to isolate and characterize the ear,” explains Dr. Maoz. “Prof. Yovel’s lab built the robot and developed code that enables the robot to respond to electrical auditory signals. My laboratory has developed Ear-on-a-Chip that allows the ear to be kept alive. We supplied oxygen and food to the organ, while allowing the electrical signals to be taken out of the locust’s ear and amplified and transmitted to the robot.

“In general, biological systems have a considerable advantage over technological systems – both in terms of sensitivity and in terms of energy consumption. Tel Aviv University researchers’ initiative opens the door to sensory integrations between robots and insects – and may make much more cumbersome and expensive developments in the field of robotics redundant.

“Biological systems expend negligible energy compared to electronic systems. They are miniature, and therefore also extremely economical and efficient. A laptop, for comparison, consumes about 100 watts per hour, while the human brain consumes about 20 watts a day. Nature is much more advanced than we are, so we should use it. The principle we have demonstrated can be used and applied to other senses, such as smell, sight, and touch. For example, some animals have amazing abilities to detect explosives or drugs; creating a robot with a biological nose could help us preserve human life and identify criminals in a way that is not possible today. Some animals know how to detect diseases. Others can sense earthquakes. The sky is the limit.”

Idan Fishel led the interdisciplinary study, a joint master student under the joint supervision of Dr. Ben M. Maoz of the Faculty of Engineering and the Sagol School of Neuroscience, Prof. Yossi Yovel, and Prof. Amir Ayali, experts from the School of Zoology and the Sagol School of Neuroscience together with –, Dr. Anton Sheinin, Idan, Yoni Amit, and Neta Shavil. The results of the study published in the prestigious journal Sensors.