A story is told about a day when motion picture director Otto Preminger, who sought a safe haven from the Nazis and achieved fame and fortune in the American movie industry, overheard a conversation that was conducted in Hungarian.

“Don’t you guys know you’re in Hollywood?” he quipped. “Speak German.”

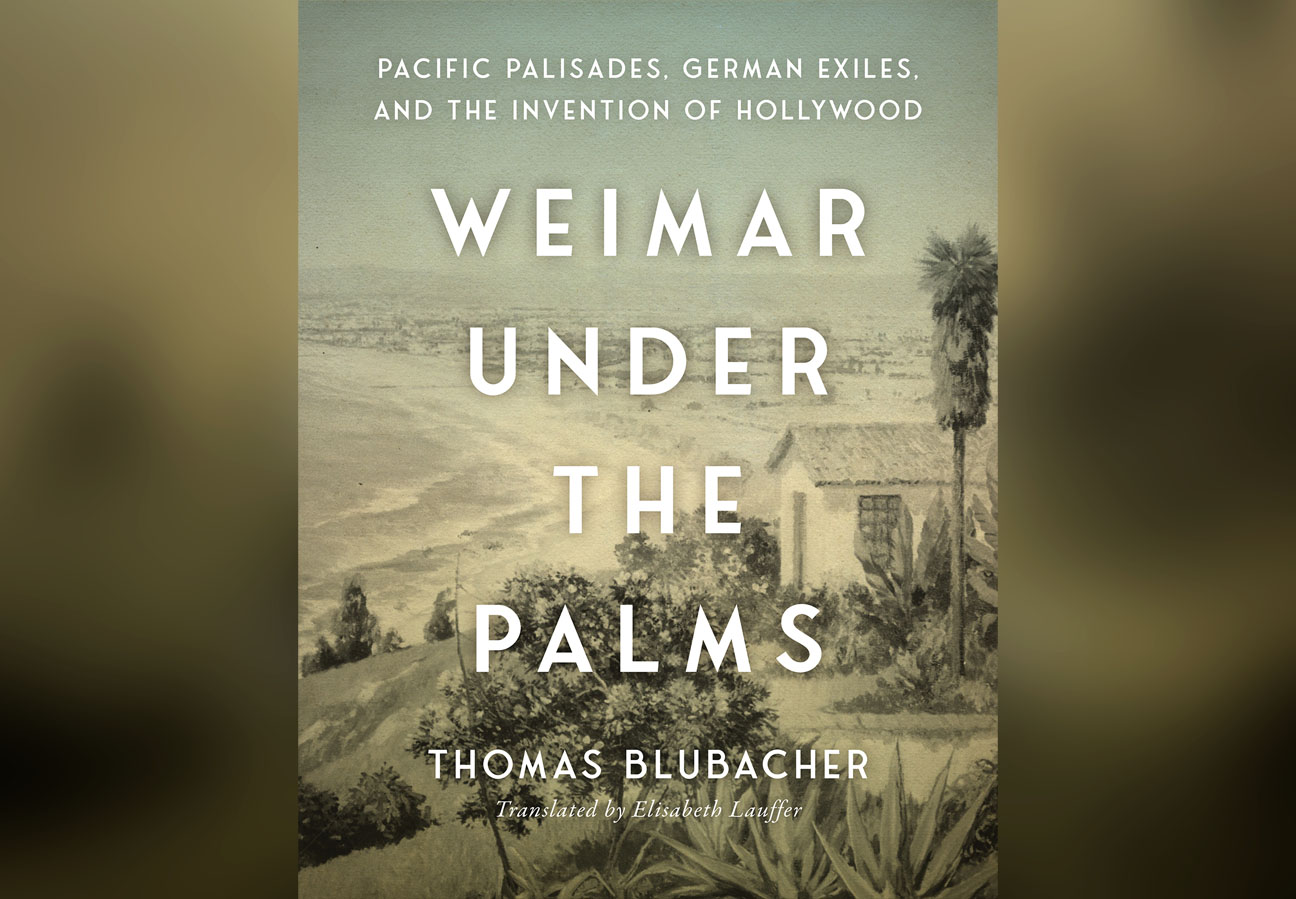

The point is made in “Weimar Under the Palms: Pacific Palisades, German Exiles, and the Invention of Hollywood” by Thomas Blubacher (Brandeis University Press), translated from German by Elisabeth Lauffer, a lively and deeply informed account of the era when Los Angeles served as a place of refuge for German, Austrian and Eastern European artists, writers, scholars and intellectuals who fled from the Third Reich.

For the Jews among them, of course, California was not merely a place to live and work but literally a matter of life and death. As Blubacher explains in fascinating detail, the immigrants richly repaid the debt by their enduring contribution to the arts and letters of America and, in particular, the motion picture industry.

Then as now, entering the United States from a foreign country was not easy. A fortunate refugee might be successful in securing the signature of a patron on an affidavit in support of a visa application. MGM’s Louis B. Mayer and Harry Warner, one of the four Warner brothers, did so for film composer Hans Sommer, who was barred from working in the German movie industry after he refused to divorce his Jewish wife and abandon their “mischling” children. They arrived on a tourist visa, and when it expired, they were forced to flee to Nogales, Mexico, where “Hans gigged in bars to pay the bills.” Even when the Sommer family was finally allowed to take up residence in America, they were categorized as “enemy aliens,” which meant an 8:00 p.m. curfew and a restriction to a five-mile radius around their home in Hollywood.

Perhaps the most distinguished refugee was the novelist Thomas Mann, the 1929 Nobel Prize laureate in literature, whose residence on San Remo Drive in Brentwood was later described as “not only a family home, a place of thinking and writing,” but also “the Oval Office of the émigré opposition to Hitler’s reign of terror in Berlin.” Significantly, the words were uttered by the president of Germany, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, at the dedication ceremony when the house was opened as a memorial and a study center in 2019.

Thus did Southern California come to called “Weimar on the Pacific.” For example, the political philosopher Herbert Marcuse, who was much later hailed as the “Father of the New Left,” had been fired from the Institute of Social Research at the University of Frankfurt under the Nazi order that banned Jews from teaching positions. On the wall of his home in Santa Monica, Marcuse posted a sign that acknowledged the continuity between the Weimar democracy that Hitler destroyed and the Weimar-in-exile that survived: “Institute of Social Research, Los Angeles Office.”

The expatriate community was centered in the Pacific Palisades but its members were not confined to its hills and arroyos, as we see for ourselves in an eye-catching locator map that appears in the endpapers of the book. Bertolt Brecht lived on 26th Street near Douglas Park in Santa Monica, Paul Henreid on the edge of Santa Ynez Canyon Park, Fritz Lang within sight of the Riviera Country Club in Brentwood, Peter Lorre in Mandeville Canyon, and Salka and Berthold Viertel at the bottom of Rustic Canyon.

The cultural and intellectual center of gravity in the exile community in Southern California, however, was 520 Paseo Miramar in the Palisades, the home of novelist and dramatist Lion Feuchtwanger and his spouse, Marta. On any given evening, their guests might include Thomas Mann himself or his brother, Heinrich, Brecht or Kurt Weill, Peter Lorre or Ingrid Bergman, Albert Einstein or Arnold Schoenberg, Franz Werfel and Alma Mahler-Werfel. Along with many of the original furnishings and 22,000 volumes from the Feuchtwangers’ personal library – another 8,000 were later donated to USC – a scrap of paper bearing a poem in Lion’s own hand is still on display: “I am a German writer/The beat of my heart is Jewish/My thinking belongs to the world.”

Since 1995, the Feuchtwanger home, now known as Villa Aurora, has served as the site of the artist-in-residence program in which Blubacher, an accomplished author and theater director, was himself a participant. Happily, Villa Aurora, the Thomas Mann Home and many other sites that feature prominently in “Weimar Under the Palms” survived the recent Pacific Palisades firestorms. “Miraculously, the buildings were spared the Armageddon’s wrath,” he reminds us. “At a time when the values these places represent come under threat on both sides of the Atlantic, their continued existence is more important than ever.”

Far beyond the Feuchtwanger home, the refugees from Nazism played a decisive role in redefining – and elevating – the cultural enterprise in Southern California. A cutting-edge director like Fritz Lang, who directed “M” and “Metropolis” while still in Germany, was reduced to working on genre movies in Hollywood, but he succeeded in creating such film noir classics as “Scarlet Street” and “The Big Heat” while working within the studio system. And when Brecht’s play “Galileo” premiered at the Coronet Theatre on La Cienega Boulevard in 1947, the producer was John Houseman (ne Jacques Haussmann, the son of an Alsatian Jew), the director was Joseph Losey, Charles Laughton played the title role and the audience included Ingrid Berman, Charlie Chaplin, Gene Kelly, Billy Wilder, Frank Lloyd Wright and Igor Stravinsky.

“It must have rankled Brecht,” Blubacher points out, “that when the gossip columnist Hedda Hopper wrote about the production in the Los Angeles Times, she never once mentioned the author’s name.”

Both the timeliness and the enduring significance of “Weimar Under the Palms” arise from the fact that democracy is always at risk from persecutors and oppressors, both actual and potential. The first artist to be granted a residency at Villa Aurora, dramatist and director Heiner Müller, according to Blubacher, “employed a bit of adhesive tape to change the ‘EXIT’ sign to read ‘EXIL,’” the German word for “exile.” So it is that exile, as Blubacher puts it, can sometimes serve as “an emergency exit” in perilous times.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is a book reviewer for the Jewish Journal.