Cancer remains the scourge it has always been – but recent years have seen significant advances in diagnosis and treatment. But there are still plenty of issues to be resolved, in both those areas – specifically, developing better ways to evaluate cancer, and developing more effective ways to determine how to choose the proper treatment as well as monitor its success.

The standard method of doing both of these in the case of solid tumors (e.g. lung, breast, prostate, colon) is via a biopsy – with doctors removing living tissue to evaluate whether cancer cells are present. But tissue biopsies aren’t necessarily the best way to diagnose and monitor treatment; a better method for both might be blood-based liquid biopsies.

Biopsies are taken to establish an initial diagnosis, seeking to determine whether or not the patient has cancer at all – and if so, how advanced it is. Biopsies are also often used during courses of treatment – to determine if a specific treatment is useful. If the number of the sample’s cancer cells falls after a course of treatment, doctors know that the treatment is working; a less positive result could indicate that it’s time to try something else.

But biopsies are invasive – and, while generally considered safe, have a degree of risk. Cancer patients, especially those receiving chemo treatments, are weak enough as it is; the last thing they need is a recurring invasive procedure. And then there is the cost; tissue biopsies can cost thousands of dollars, and while most patients aren’t paying out of pocket for them, the cumulative cost of multiple tissue biopsies for patients who are often treated for years is certainly a factor in the high cost of medical care in the US. Either way, tissue biopsies are far from an ideal procedure.

A better alternative

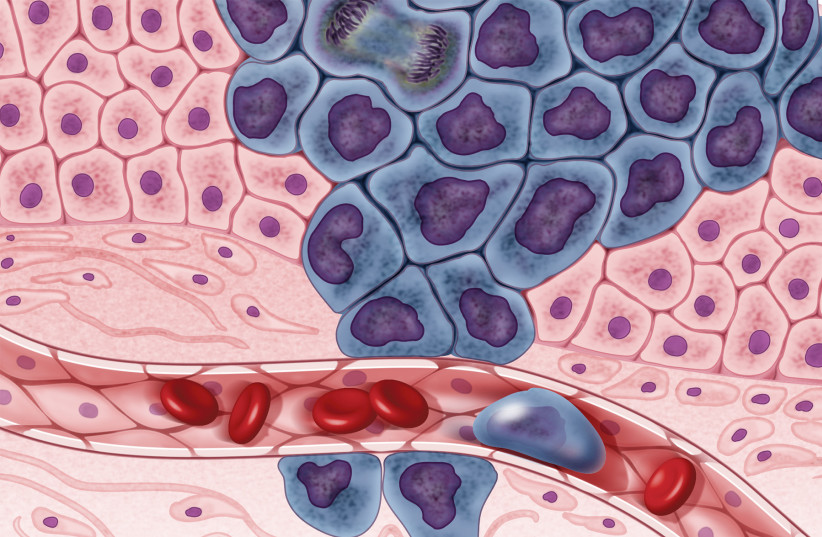

A better alternative for both initial diagnosis and treatment selection/monitoring may be liquid biopsies – where analysis of circulating tumor cells (CTC), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and exosomes that have leaked into the bloodstream. Especially in cases of metastasized cancers, infected cells undergo intravasation – basically an invasion of the bloodstream – to spread. By drawing blood and analyzing the cells for cancer biomarkers, doctors can determine whether or not a patient indeed has cancer – and how bad a case it is. In recent years, technology has advanced to the extent that the results of liquid biopsies for diagnosis and treatment monitoring are very close to those of tissue biopsies.

Perhaps more significantly, liquid biopsies could help effectively monitor treatment progress and help choose the best treatment option. If the level of free cancer cells falls, that’s a good indication that treatment is effective; if the number of cells remains steady or grows, alternative treatments need to be considered.

The speed and ease with which liquid biopsies can be administered – the procedure is very similar to a standard blood test – means that doctors can get answers much more quickly, an important advantage over tissue biopsies – where, because of resource shortages, often have to be planned weeks or even months in advance. Patients are thus at risk of continuing what may be an ineffective or irrelevant treatment far longer than necessary – while missing out on other treatments that could help them get better. With liquid biopsies, doctors can get answers much more quickly, saving patients from invasive treatments that may not be doing them any good anyway.

And while helping patients get better is clearly the priority, today’s high medical costs need to be taken into context. Besides not helping – and even possibly hurting them – leaving patients to undergo ineffective and expensive treatments wastes resources that could be put to better use, driving up care costs for everyone.

Faster, less complicated, and more accessible liquid biopsies could help fix these treatment issues – and in fact, experts see increased use of liquid biopsies as “transformative,” an important step in the evolution of medicine – from diagnostic medicine, where general treatments were developed for a mass of patients, to personalized medicine, where doctors were able to ensure that the appropriate treatments were rendered to each patient individually, to precision medicine, where doctors get clear answers on the effectiveness of those treatments, and can make quick and effective decisions on how to treat patients.

Although doctors often prefer to do things the “traditional” way, liquid biopsies can be valid alternatives to tissue biopsies; several have received FDA approval for various cancers, and more are in the pipeline.

By embracing liquid biopsies, doctors can help their patients deal more effectively – and comfortably – with their cancers.

The writer is the CEO of start-up Bioview.