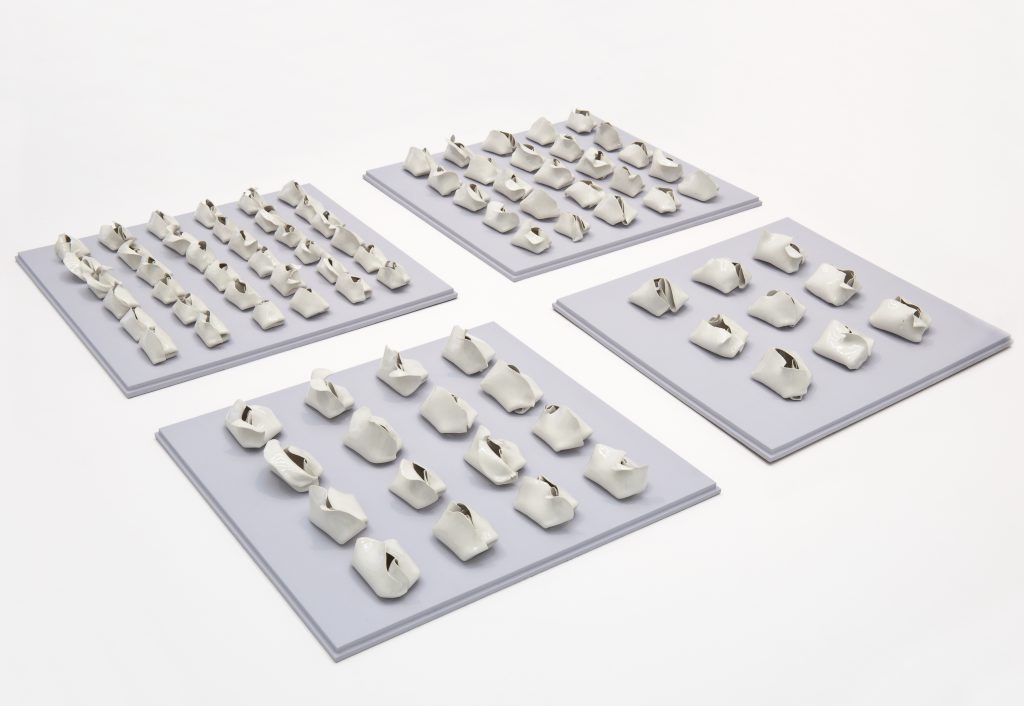

HANNAH WILKE MADE HER FIRST VAGINAS in the early 1960s. They were small vulval shapes formed from clay or pliable kneaded erasers—sometimes bearing irreverent, punning titles (“Needed-Erase-Her”)—that Wilke described variously as “one-fold gestural sculptures” or “wounds.” She affixed the sculptures to postcards and other surfaces. In some cases, she arranged them according to the geometric conventions of minimalism, conveying order through their repetition—her husband, Donald Goddard, compared them to headstones. When she laid them out haphazardly, the effect was organic. “My folded clay pieces are like little pieces of nature, a new species,” Wilke said. “They exist the way sea shells exist.”

An iconic but not always respected feminist artist, active from the ’60s until her untimely death in 1993, Wilke is the subject of a large-scale retrospective at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, one of the first exhibitions to pay tribute to her work’s conceptual rigor and reflect the breadth of her endeavors. Her pieces also appear in another new exhibition, Erotic Abstraction, at Acquavella Galleries in Manhattan. Frequently grouped with contemporaries like Carolee Schneeman, Lynda Benglis, and Ana Mendieta, Wilke worked across a range of old and new mediums, from pastel drawing to video. Often, she made work from unconventional materials, like laundry lint or chewing gum. (“I chose gum,” she said, “because it’s the perfect metaphor for the American woman—chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out and pop in a new piece.”) Throughout the 1970s, Wilke art-directed and posed for photographs she called “performalist self-portraits,” and preserved emotionally charged images from her live performances that look like film stills, prefiguring the work for which Cindy Sherman would later become famous. In these, she sometimes went full cheesecake, playing with idealized femininity—and knowingly inviting scrutiny—by styling herself as a sex symbol. The images, in which she often appears naked, simultaneously attract and indict the male gaze.

It would be easy to assume that art like Wilke’s, made in the 1960s and ’70s, would feel dated now. Certainly this is true of the work of some of her contemporaries: One thinks of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, a campy, banquet-style table setting of vulval dinner plates honoring great women from history—a true relic of Second Wave feminism. By contrast, many of Wilke’s pieces on similar themes achieve a renewed relevance by emphasizing the mutability of the vaginal motif, posing questions about gender essentialism that her feminist contemporaries largely declined to ask. At first glance, the repetition of objects in pieces like Needed-Erase-Her #14—a five-by-five grid of vulval sculptures—suggests an unmediated sameness, but closer inspection reveals the dissimilarity of the shapes, and the pliability of the material itself. Suddenly, the grouping suggests instead the impossibility of fixity. Instead of reifying the vulva’s centrality to feminist symbology, the piece emphasizes the constructedness of the organ and all that it signifies.

In the photography that followed, like S.O.S Starification Object Series, Wilke likewise reveals the subversive possibilities of repetition, the persistent inexactitude of the nonmechanical copy. In the photos from the series, the artist, topless and stuck all over with tiny chewing-gum one-folds, styles herself as a movie star, cowgirl, virgin, and housewife in curlers. In these riffs on stock images from advertising and fashion, which both mime and marr the image of the idealized woman, Wilke simultaneously enacts and displaces the conventions of gendered representation. It’s but one instance of the way that Wilke eschewed the revisionist stagecraft and strident political messages of her contemporaries, always leaving room in her work for uncertainty, suspicion, and doubt.

WILKE’S EARLY WORK is sometimes compared to that of Eva Hesse, with whom she is paired in Erotic Abstraction. Both women used the language of minimalism and cheeky humor to explore materiality and sensuality, and to challenge the machismo of the art world. Both were Jewish and grew up in the shadow of the Holocaust. The German-born Hesse was part of the last Kindertransport out of the country in 1938; Wilke, born Arlene Hannah Butter, was raised by Hungarian Jewish parents on New York’s Lower East Side. “My consciousness came from being a Jew in World War II,” she said in a 1989 interview. “I realized what it would be to be annihilated just for a word.” Unlike Hesse, who made clusters of sculptures evoking body parts from latex and resin, however, Wilke often boldly made her own body the center of her work. As a result, Hesse, who died at 34 from a brain tumor, was read during her brief life as playful—having a laugh with the mainstream art establishment—while Wilke was more likely to be viewed as a femme fatale: provoking, taunting, perhaps laughing at others’ expense.

This was not always a popular pose. Wilke’s use of vaginal forms earned her a reputation as “confrontational” early in her career. “By now everyone is quite well aware that Hannah Wilke does cunts,” a 1975 profile by Mark Savitt in Arts Magazine snidely began. This attitude toward Wilke has persisted into the present. Her early, vulval sculpture work was again met with patronizing skepticism when it resurfaced after being overlooked for years. Reviewing a 2008 show of Wilke’s “largely forgotten” sculpture in The New York Times, critic Benjamin Genocchio wrote that the exhibit was “not easy to experience or even to like, given the confrontational, repetitive use of female sexuality.” Feminist critics were not necessarily more inclined to praise Wilke. In 1976, art critic Lucy Lippard disparaged her as a “glamour girl . . . who sees her work as ‘seduction’” in an essay in Art in America, chastising her for confusing “her roles as beautiful woman and artist, as flirt and feminist.” (In response, the same year, Wilke made a poster bearing an image of herself topless that read: “Beware of Fascist Feminism.”) As the artist Kiki Smith observed, thinking of Wilke, female narcissism “always has to be paid for.”

But as the Pulitzer Arts retrospective demonstrates, far from undermining Wilke’s work, the multivalent possibilities that lie at the intersection of “flirt and feminist” remain unnerving and powerful decades later. The scalloped pastel peach and pink folds of her labial latex sculptures, which flutter open suggestively on the gallery wall, are both funny and forbidding, carnal and industrial, vulnerable and tough, studded with metal snaps and push pins. Wilke wrote in a letter that they were meant to connote “the loose arrangements of love, vulnerably exposed.” It is this mischievous insistence on nodding to complexity that makes Wilke’s work feel more up-to-date than a piece like Chicago’s Dinner Party. Simply put, Wilke’s vaginas are more tongue-in-cheek.

In her 2010 monograph on the artist, Nancy Primenthal wrote that Wilke “insisted on exploring and expressing the body’s most insistent and powerful conditions.” Nowhere is that more true than in her haunting final work: Diagnosed with lymphoma at 42, Wilke documented her death (with Goddard’s help) with disconcerting candor in her last work, Intra-Venus, a photo series showing the ravages of illness and chemotherapy—as well as moments of characteristic wit, audacity, and joy. She also made pieces out of her own hair and watercolors of her IV. They were a chronicle of “physical transformation as violence,” as the artist Joanna Freuh put it in her book Monster/Beauty. (Goddard went on to edit over 30 hours of video footage of Wilke taken in the last years of her life, turning them into an arresting, subtly cacophonous 16-channel video installation, The Intra-Venus Tapes, 1990-93.) Some of the pieces from Intra-Venus are on view at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation. So is an image that darkly presaged the series: a photograph of the artist’s mother, Selma Butter, dying of cancer more than a decade earlier, her mastectomy scar fully visible. Selma’s skeletal form is juxtaposed with Hannah’s: Both women are topless, one approaching death, the other in the prime of youth. It’s another example of a discomfiting serialization of women’s forms.

It’s easy to celebrate the fact that Wilke’s work lands with such weight now, that it will find a larger audience through these two new exhibitions—and we ought to. But we must go further than facile appraisals of Wilke’s “message of self-love, body positivity and women’s agency,” as a review of the Pulitzer show in The Art Newspaper reads. We must recognize that renewed interest in Wilke’s work is not simply an effect of feminism, but a reflection of our continued failure to actualize its goals. “The best way to succeed as a woman artist is to be old,” Jillian Steinhauer wrote in The Believer in June, referring to the way artists like Agnes Denes and Bettye Saar are “discovered” late in life, their robust oeuvres ready to be consumed whole. The work of such women has become the exception to the art world’s misogynistic rule, in which only “11% of all acquisitions and 14% of exhibitions at 26 prominent American museums over the past decade were of work by female artists.” The old woman artist is treated “as an archetype,” Steinhauer writes, “like the wise crone in fairy tales.” Though Wilke didn’t live to be an art crone or to see herself appraised anew, the resurgence of interest in her work fits this trend. But even in its moment of revival, Wilke’s work defies neat narratives of empowerment. The retrospective is most galvanizing when understood as, at best, a partial victory, just as the art itself is most energizing when seen through the lens of its persistent indeterminacy.

Nina Renata Aron is a writer and editor based in Oakland, California and the author of Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls: A Memoir of Women, Addiction, and Love.

The post Female Forms appeared first on Jewish Currents.