Celebrated Jewish writer Franz Kafka may have written his most famous works, including the novella “The Metamorphosis,” in German, his mother tongue.

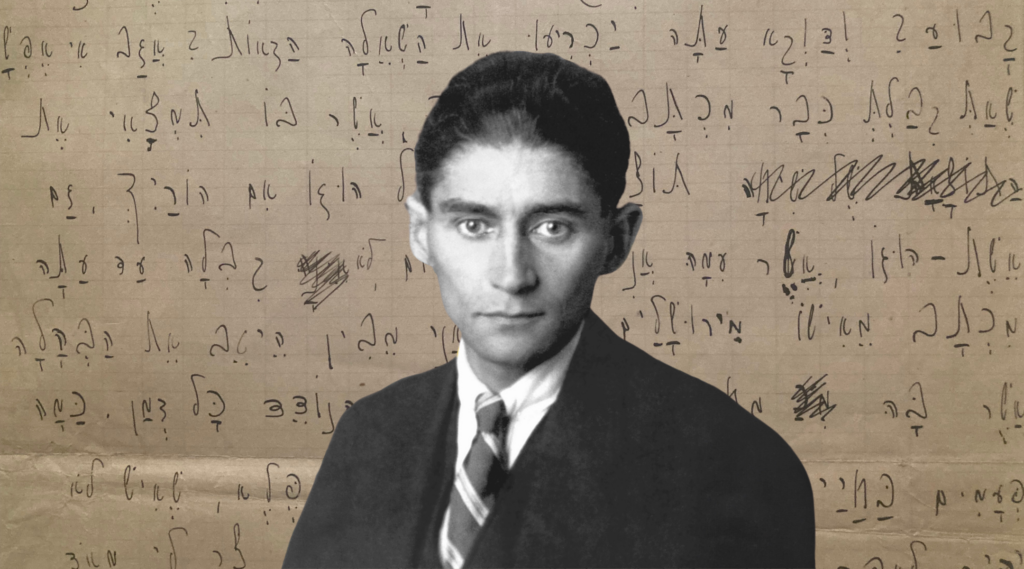

But Kafka was proficient in other languages, too, including Hebrew — a fact that some scholars point to when making the case that his Jewishness played a large role in his creative life. And now, visitors to “Franz Kafka,” an exhibit currently on display at the Morgan Library and Museum in Midtown, have the opportunity to view some of Kafka’s original Hebrew writings.

The small but wide-ranging exhibit explores the lasting legacy of the Jewish icon. On view through April 13, the exhibition presents, for the first time in the United States, some of the “extraordinary holdings” of the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, including manuscripts, correspondence, diaries and photographs related to the writer, whose works are so canonized that the term “Kafka-esque” has become part of the English lexicon.

Among the items on view include the original (German) manuscript of “The Metamorphosis,” a model of the Kafka family’s apartment in Prague, and endearing, funny postcards he sent to his favorite sister, Ottla.

Of particular note for Jewish fans, however, are two examples of Kafka’s writings in Hebrew, including a draft of a letter, written in 1923 to his Hebrew teacher, a young woman named Puah Ben-Tovim.

“Kafka learned some Hebrew as a boy — enough to get through his bar mitzvah — but in his mid-thirties he returned to the language and began to study it seriously, with the help of books and private lessons,” the placard next to the letter to Ben-Tovim states. “He did not know how to write ‘Europe’ in modern Hebrew, so here he wrote it out phonetically instead, followed by ‘laugh not’ in brackets.”

The other Hebrew text on view is a small notebook, dated “1917 or later,” filled with German words and their Hebrew translations. “These words give us an insight into Kafka’s preoccupations at the time. Many concern matters of health,” the accompanying text reads. “On this page we see ‘illness, ‘enema,’ and ‘I weigh.’” (Yes, the writer was something of a health nut, and would die of tuberculosis at age 40.)

In his award-winning book, “Kafka’s Last Trial: The Case of a Literary Legacy,” Israeli-American author Benjamin Balint explores Kafka’s “transformative” connection to the Hebrew language. “It shows a man grappling with questions of identity, inheritance, and destiny, not as abstractions but as lived realities,” Balint told the New York Jewish Week in an email. “Even in his tentative Zionist leanings, one senses the imagination at work — the way Hebrew might serve as a bridge, a home, or even a reclamation of self.”

Balint, who is based in Israel, will be at the Morgan next month to lead an in-person gallery tour on Wednesday, Feb. 5, and he will also present a virtual lecture that same day. To learn more, click here.

“Franz Kafka” is on view at the Morgan Library and Museum (225 Madison Ave.) through April 13.

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.