Hearing the Silent Aleph –

Vayakhel

©️Rabbi Mordecai Finley, 2025

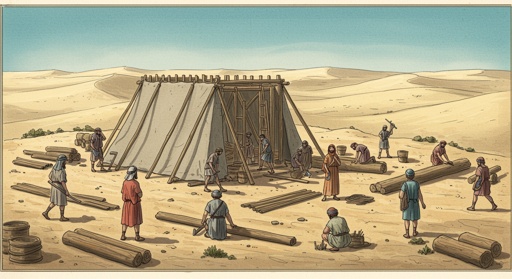

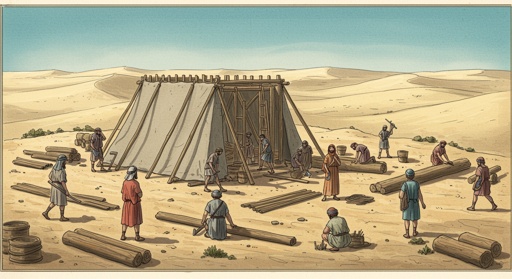

This week’s Torah portion, Va-yakhel, is the first of two Torah portions concerned with the building of the Mishkan. In next week’s portion, Pekudei, we find the actual dedication of the Mishkan. I would like to focus in these few words on what happened just before the people got to work on building the Miskhan.

We’ll start with selection from the a midrash on the giving of the 10 Commandments in Exodus chapter 20, a well-known rabbinic commentary on that foundational event in the Jewish religion. Think of this commentary as a poem. Here is my paraphrasing and commentary on the poem.

When God began to speak the 10 Commandments, the people said “This is too much to bear. Just speak the first commandment, and let Moses tell us the rest.”

If God would speak to you right now, say a few things that you must know and must do, and a few things you must never do, do you know in your heart of hearts what God would say? Could you bear it? We might say, “Whatever You need to say to me, God, please just keep it brief.”

The Midrash continues,

God began to speak the first commandment, “I am Adonai your God, Who took you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.” The people said, “This is too much to bear. Just speak the first word of the first commandment, and let Moses tell us the rest.”

Even that first commandment was too much. Not the content of the commandment, perhaps, but the fact that the heart of the universe peered into your heart and had something to say.

God relents, and will speak only the first word:

God began to say just the first word of the 10 Commandments, “Anokhi,” “I.” The people said, “This is too much to bear. Just say the first letter.”

God’s saying “I” implied a “You.” The people weren’t ready for an “I and You” moment with God.

God agrees only to speak the first letter. The first letter of the first word of the 10 Commandments, “Anokhi,” is the silent “aleph” – not “ahh” – just nothing. Aleph is a placeholder for a vowel. We assume that God articulated the silent aleph. The story ends here.

What happened? God communicated to the people the silence before speech, the meaning before words. According to the story, Moses hears the rest, and then God writes the words on stone tablets. Moses is to deliver this petrified (as in “turned to stone”) speech to the people.

Last week’s Torah portion, Ki Tisa, tells us how that went. Not well. The day that Moses arrived, the people broke bad. Just before Moses got down the mountain, they had Aaron form the Molten Calf. According to Exodus 32, they danced and frenzied and worshipped that Molten Calf.

I don’t think that the main motivation of the people was to worship the Molten Calf. I think their main motivation was to hide from God, to use the Molten Calf as a mask. They couldn’t bear being spoken to by God. The people needed to do something, anything, to get that silent aleph out of their heads. That silent aleph was driving them crazy.

The story in Exodus 32 tells us that Moses, upon seeing the people worshipping the Molten Calf, smashed the petrified commandments, thinking the people didn’t deserve them, that they had committed apostasy. God backed Moses up. I think Moses and God, as presented in this story, were too angry to understand what was really going on.

The people were terrified. They weren’t guilty of apostasy, in my mind; they were guilty of avoidance, in the extreme. They wanted to do anything but face what was happening inside of them. Worshipping the Molten Calf was a way to regress to rigid thinking. We all do that. When we can’t bear the truth of a moment, we have to shut down our thoughts. If we were attentive to the truth of the moment, we might have to change our lives.

I don’t think the people were against the 10 Commandments. According to this midrash, the people didn’t know what the commandments were. Moses hadn’t told them yet. I don’t think the people in this story thought very much about what the commandments contained. They just weren’t thinking.

I think they just couldn’t stand the silent aleph. That silent aleph spoke eternity. Everything that could be known and cannot be known. All being and all non-being. God’s being, communicated in the Un-sound, the No-thing.

Perhaps they thought, in retrospect, they should have just listened to what God wanted to say, and then tuned it out. Listening to the silent Aleph was far more difficult than they could have imagined.

Here is a thought experiment. Think of someone that you love. Imagine sitting across from them, looking at each other’s eyes. Blink and breathe, that’s it. No speech. Just the presence and the eyes. In this thought experiment, do it for a few minutes straight. Try imagining it.

Eventually, you will see each other’s souls. You will blink your way into theirs, into knowing the God that fills their souls, the eternity-filled silence of God. Now imagine you and this other person are being ordered to this, but you have this one way out. If it becomes too uncomfortable, you can just go into the next room where a party is happening. Drinking, dancing. A calf-shaped piñata.

God wanted us to look into God’s eyes and God’s heart. “Don’t follow your own eyes and hearts after which you go astray,” God would later say to the people.

“Just for a few minutes, set your eyes and hearts upon me.” The people chose the party option.

Last week’s Torah portion ends, in Exodus chapter 34, with an anything but clear reconciliation. Here is the essence. The commandments were engraved on new tablets. Moses brought them down the mountain. The people accepted the commandments, all the words. Moses explained everything.

.

Why could they listen this time? The way the ancient rabbis tell it, the people changed because they decided to. They sat quietly the whole day, waiting for Moses to come down the mountain. No drinking, no eating, no dancing, no Molten Calf. The ancient rabbis say that in order to be present to the Presence when Moses came down the second time, the people created, of their own accord, a deep Sabbath, a Shabbat Shabbaton. The ancient rabbis say that in deciding to stay quiet, and do nothing but stay quiet, the people spontaneously invented Yom Kippur. Our observance of Yom Kippur is, at its core, a reenactment of our receiving the second Tablets. A quiet we imposed on ourselves so that we could listen.

In my telling, they decided to place their eyes upon God, eyes meaning the perceptive apparatus comprising their hearts, souls and might, for a full few minutes, a few minutes that opened a gate into eternity.

They breathed in the silent aleph of this Sabbath for the soul. After the Sabbath of receiving the second Tablets, they got busy building the Mishkan, the focus of this and next week’s Torah portions.

All you could hear was the work. The people didn’t talk much that day.