It was, I thought, a Jewish food writer’s dream assignment. Nearly four years ago, during the first autumn of the COVID pandemic, I sat down (virtually) with food superstar Ina Garten to learn about her childhood memories of home, family and food — and the impact those memories had on her career as a widely beloved foodie, television personality and author of, at that time, 12 enormously successful cookbooks.

The interview was for The Nosher, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency’s partner food site, and as such I was particularly interested in hearing about Garten’s Jewish food memories. Given the number of classic Ashkenazi recipes she has in her books — from chopped liver to stuffed cabbage, chicken soup to rugelach — I was sure there was lots to unpack. So I asked what I assumed was a softball question to get the conversation going: Do you have memories of your childhood kitchen and food?

“I don’t. I didn’t have the happiest childhood,” Garten told me.

Garten is known for her velvety voice and easy laugh, and her books are filled with quotes about the role that a home plays in one’s life and how the kitchen is the heartbeat of the house. So I was shocked to learn that her life before she met Jeffrey Garten, her husband of 56 years, was unhappy and that it was a subject from which she stayed away.

“I think a lot of what I do is creating what I always wanted rather than a memory of something,” she said then. “The minute I got married I really started cooking. I was never allowed to cook. I was never allowed in the kitchen.”

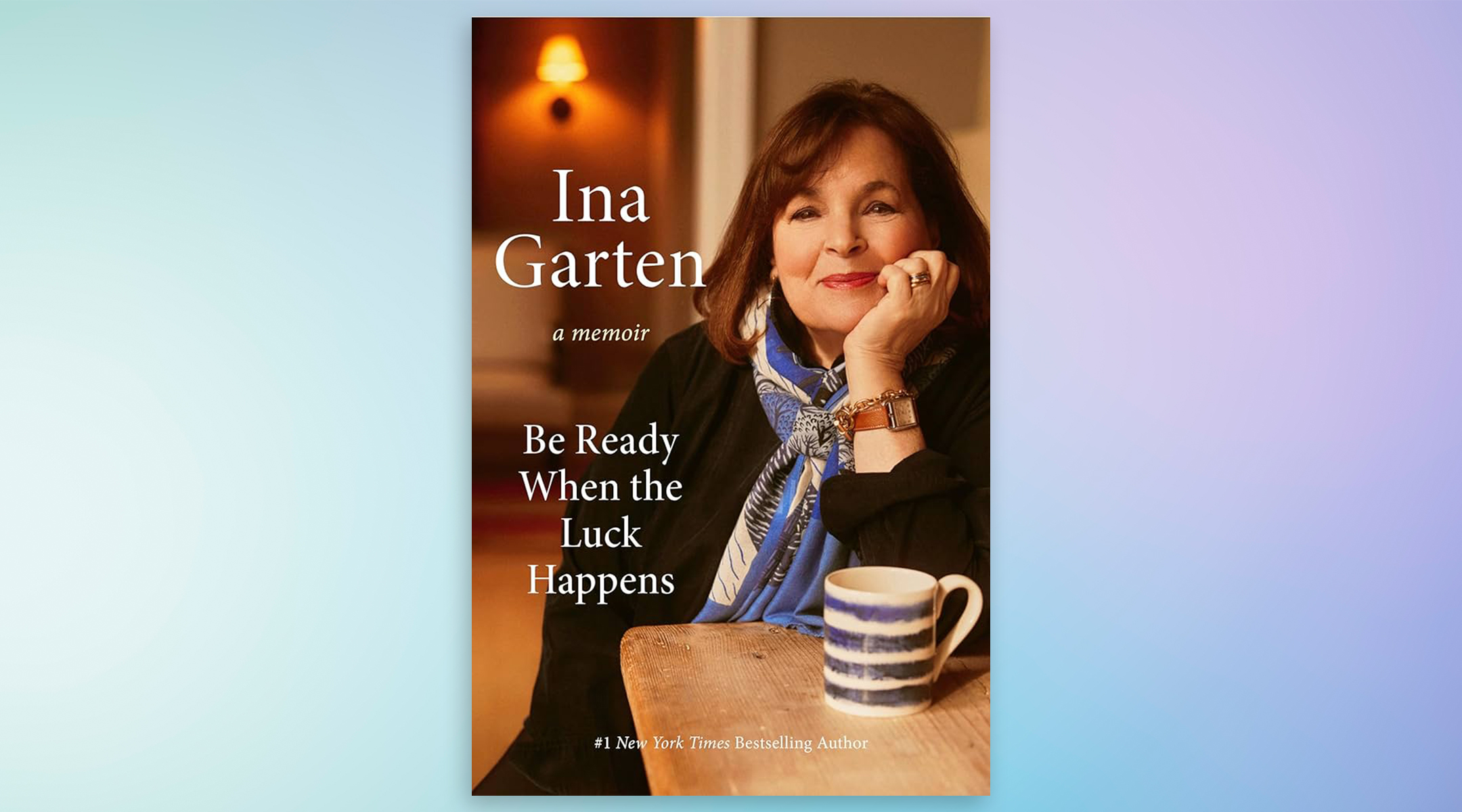

Lucky for Garten’s fans, in the years since that interview, Garten has apparently reconsidered her reticence. In her new memoir, “Be Ready When the Luck Happens,” Garten opens up about her painful childhood, first in Brooklyn and then in Stamford, Connecticut, and the winding road that led her to carving out a place in the food world.

Her love of cooking and hosting clearly didn’t come from her mother. Garten describes her mother as emotionally detached, a person who “cooked and didn’t enjoy it.” Garten’s father, a physician, was tall and handsome, but with a dark streak to his personality.

“When he got angry,” she wrote, “which was often, anything could happen. He’d hit me or pull me around by my hair.” Their parenting style was tyrannical. Her mother’s approach to child-rearing was, wrote Garten, “basically making sure that we [ my brother and I] did what she thought we were supposed to do.” They generally disapproved, she wrote, of any decision she made that was different from theirs.

It wasn’t all cruel and unhappy. Garten has warm memories of her paternal grandparents, Bessie and Morris Rosenberg, who spoke only Yiddish when they arrived in America from Russia and Poland.

Bessie was “always cooking, and like all good cooks, she was happiest when she was feeding people,” Garten writes. “Her steaming pots were filled with traditional Jewish dishes that were probably overcooked and under seasoned, but simple and delicious.”

After Ina and her family left Brooklyn for Connecticut, her grandparents would visit them every other Sunday, bringing a haul of Jewish foods with them.

“There was a deli around the corner from where they lived,” she told me, “and they would bring everything from chopped liver to rye bread, cookies and hot dogs. I think they thought we didn’t have food in Connecticut.”

Bessie Rosenberg died when Ina was still young and other than her description of her grandmother, whom Garten says she resembles, there are no warm family- or food-related memories in this memoir — until Jeffrey Garten enters the scene.

The couple met as teenagers – she was in high school, he was a freshman at Dartmouth College. They married when she was 20, and he was 22. In their first apartment, Garten told me, the first thing she did was buy furniture and rugs.

“I wanted to create an environment that felt warm and cozy because I was hungry for it,” she said.

Garten taught herself to cook by working her way through Craig Claiborne’s “New York Times Cookbook.” As a newlywed, she took flying lessons, worked in a women’s clothing store, finished college, traveled through France with Jeffrey on $5 a day and then moved to Washington, D.C. There she worked for the White House by day and returned home in the evening to recreate some of the memorable dishes they had eaten during their travels in Europe.

As her boredom with her government job grew, Garten searched for her next gig — one in which she could be her own boss. “I’m a terrible employee,” she writes, “because I hate being told what to do — that’s what my life was like growing up!”

Through a combination of searching and serendipity, Garten came across a small ad in The New York Times for a “Catering, Gourmet Foods, and Cheese Shoppe” in the Hamptons. She loved its name — Barefoot Contessa — made an offer to purchase it, which was accepted, and began the next trajectory of her life.

Her autobiography details ways that this change was unsettling for Garten, who reveals in the book that she asked her husband for a trial separation early in her time at Barefoot Contessa. But it was also a pivotal point for her career, yielding success at her first Barefoot Contessa store in Westhampton, then in a move to another down the street, then moving farther east to open another food store in East Hampton.

Despite her growing renown, Garten was plagued with self-doubt, and she came to realize that the critical voice in her head was, she wrote, “actually my parents’ voice, not mine.”

She went on, “It’s really hard to separate yourself from that voice, but I started telling myself, That’s what my mother would have said. Everything you’ve done has come out better than you could have imagined, so listen to your own voice.”

It was that legacy of abuse and negativity that informed her decision to not have children.

“I had such a horrible childhood with my parents, with emotional and sometimes physical abuse, I couldn’t understand why anyone would want to recreate that family,” she wrote. “I didn’t. There’s a saying, ‘What goes in early goes in deep.’ After my experience, my mind was closed to the possibility of having my own child.”

In 1996, at age 48, Garten stepped away from the retail food business. She pivoted to do what her customers and friends had been begging her to do: write a cookbook. “I wanted to make easy recipes that anyone could prepare and know their guests would be delighted,” she wrote.

The book she produced — “The Barefoot Contessa Cookbook,” published in 1999 — was unlike others on the market. It had only 75 recipes and lots of full-page photographs. It was the first of 13 cookbooks and, over the course of more than 25 years of writing them, more than 13 million copies have been sold.

Two of Ina Garten’s books, “Barefoot Contessa Parties!” and “Modern Comfort Food.” (Clarkson Potter)

“The food we enjoy most connects to our deepest memories of when we felt happy, comfortable, nurtured,” Garten writes. “It could be something from childhood (definitely not my childhood — my mother, who was a trained nutritionist, never served anything remotely comforting!) or a taste that somehow made us feel good, even if we didn’t know why.”

One of the recipes in her cookbook “Barefoot Contessa Family Style” for Parmesan Chicken actually came from a dish that her mother used to prepare, “one of the few delicious things she made,” writes Garten.

At the time of my interview with Garten I was deflated when she declined to discuss her childhood and her food memories, but she made it clear in her memoir that she had spent her life skirting around those topics.

She was terrified to write a memoir because she knew that if she committed to doing so, “I would have to be open, honest and vulnerable,” she writes.

“I had spent so much time avoiding the painful periods in my past, especially my childhood, that I wondered if I’d be able to open those doors. And what would be behind them?”

Towards the end of the book, she asks herself if her life unfolded the way it did because she wanted to overcome her parents’ harsh criticism — or despite it.

“I’ll never know,” she wrote, “but one thing I know for sure is that everything changed when I met Jeffrey. This is when my life began.”

Support the Jewish Telegraphic Agency

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, (JR) can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.