(JTA) — When Alyza Lewin became a bat mitzvah in 1977, the fact that she had a ritual ceremony at all was still relatively revolutionary in Orthodox circles. But she took the rite of passage a step further, and did something that, for Orthodox Jews at the time, was considered the exclusive province of men.

She chanted the Scroll of Esther, known as the Megillah, in front of a mixed-gender audience in suburban Washington, D.C. on the festival of Purim. Among the crowd were her grandfathers, who were both Orthodox rabbis. Lewin was the eldest of two daughters, and her father wanted to find a ritual she would be allowed to perform while remaining within the bounds of traditional Jewish law.

“My father, when it came time for the bat mitzvah, was trying to figure out what was something meaningful that a young woman could do,” she said. “So he decided: My Hebrew birthday is four days before Purim — he would teach me how to chant Megillat Esther.”

For many modern Orthodox women more than four decades later, women’s Megillah readings have moved from the cutting edge to squarely within the norm. The increasing number of women’s readings is an indication of the growth of Orthodox feminism — and its concrete expression in Jewish ritual.

According to the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, at least 105 women-led Megillah readings, for both mixed-gender and women-only audiences, are taking place worldwide this year. In 2019, according to JOFA, the number hit a peak of 139, up at a relatively steady pace from 63 in 2012, when the group began collecting data. The number of readings dipped last year due to COVID-19 precautions, but JOFA expects this year’s total to come close to the pre-pandemic high once congregations get around to notifying the organization of their events.

JOFA’s executive director, Daphne Lazar Price, said she had observed but did not quantify a related phenomenon where she’s seen “tremendous growth:” girls marking their bat mitzvahs with Megillah readings, as Lewin did.

“Instead of a traditional Torah reading service or women’s tefillah [prayer] service or a partnership minyan service, we’ve seen a lot more… girls read, in part or the entire, Megillat Esther,” Price said.

Alyza Lewin’s personal Megillah scroll cover is embroidered with an image of Mordecai being led on a horse by Haman on one side, and her name on the other side. (Photos courtesy of Alyza Lewin. Design by Jackie Hajdenberg)

Although traditional Jewish law, or halacha, obligates women to hear the Megillah on par with men, many more traditionalist Orthodox communities still do not hold women’s Megillah readings. Some Orthodox rabbis may believe that women need to hear the scroll chanted but should not themselves chant the scroll. Another objection stems from the idea that synagogues should gather the largest audience possible to hear the Megillah, rather than fragment the crowd into smaller readings.

Still others worry that a women’s Megillah reading will act as a sort of gateway to non-Orthodox practice more broadly. Gender egalitarianism is one of the principal dividing lines between Orthodoxy and more liberal Jewish movements, and some Orthodox rabbis say women who organize a Megillah reading of their own may then venture into chanting Torah or leading public prayers, which women in the vast majority of Orthodox communities are not allowed to perform.

“The fear is, if we give a little, it’s a slippery slope and once we allow women’s Megillah readings people intentionally will manipulate or maybe even accidentally just get confused,” said Rabbi Dovid Gottlieb, an Israeli Orthodox rabbi formerly based in Baltimore, describing some rabbis’ concerns regarding women’s Megillah readings in a lecture last month surveying a range of perspectives on the topic. “If women’s Megillah readings are OK, then women’s Torah reading is OK, then women rabbis are OK and before you know it, I don’t know what.”

In recent years, a growing number of Orthodox women rabbinic leaders have weighed in on the question as well. Maharat Ruth Friedman, a spiritual leader at the Orthodox congregation Ohev Sholom: The National Synagogue in Washington, D.C., said women reading Megillah may feel more acceptable to Orthodox communities that see women’s performance of other rituals as a step too far away from Orthodoxy.

“It is kind of the one semi-kosher or kosher thing that women in more [religiously] right-wing communities can do,” Friedman said. “It doesn’t necessarily mean that the rabbis allow them to meet in the synagogue space, but at least that there is a contingent of women who will go to them.”

In some communities, women’s Megillah readings might take place in private homes or in other spaces outside the synagogue. Some Orthodox rabbis permit women to read the Megillah for other women, but prohibit it in front of men.

The idea of feminist Megillah readings has become so mainstream that it was a storyline on “Shababnikim,” an Israeli comedy series about renegade haredi Orthodox yeshiva students. One of them is alarmed by his fiancee’s determination to read the Megillah for a group of women and barges in to stop the reading. He later decides that despite his discomfort he should be more flexible in the future, within the constraints of Orthodox law, to make the woman he loves feel respected.

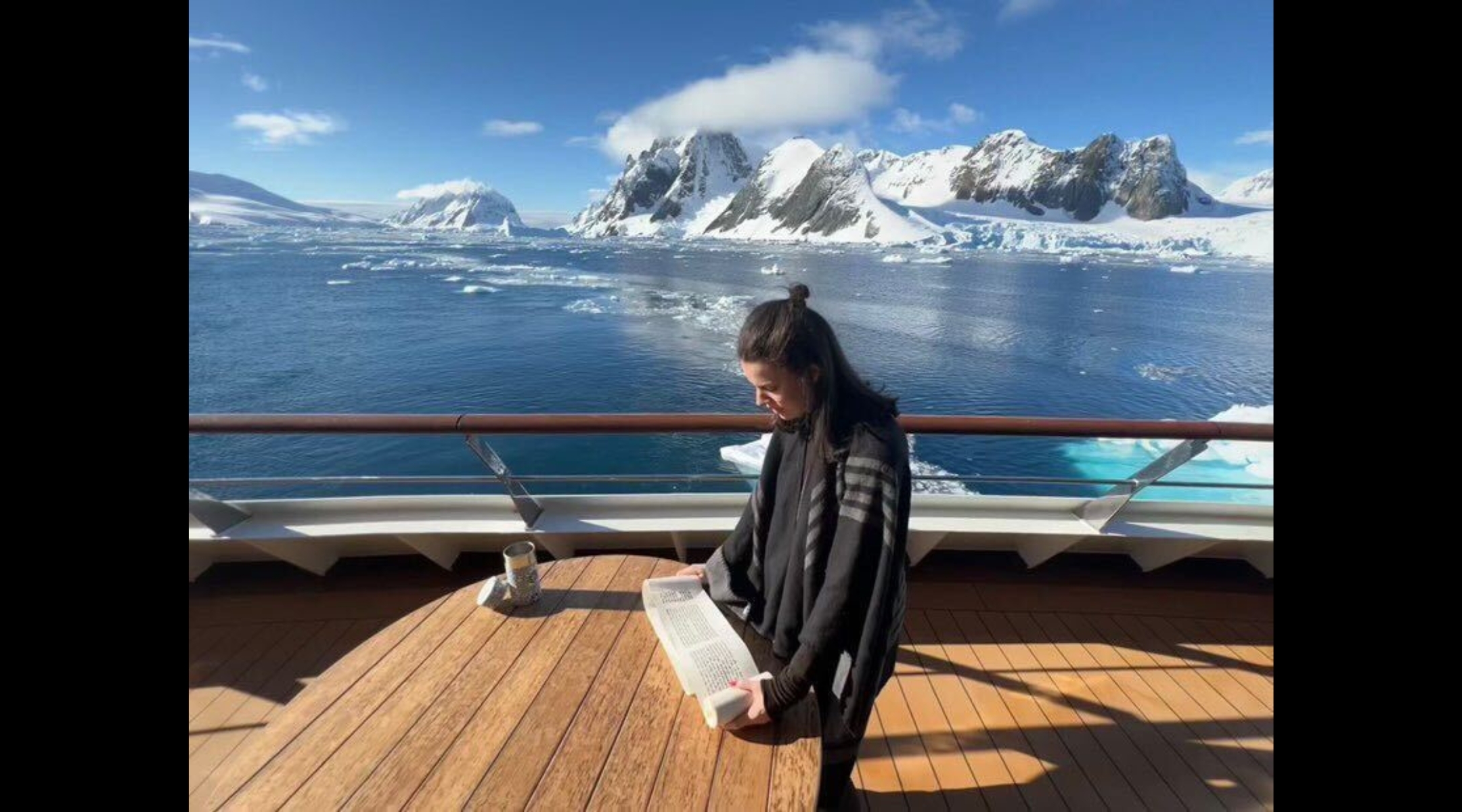

As women’s Megillah readings have increased in popularity, they have reached the farthest parts of the globe, even reaching as far south as Antarctica. (Courtesy of Raquel Schreiber via JOFA)

At the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale, a liberal Orthodox synagogue in New York City, women have been reading Megillah for decades. Founding Rabbi Avi Weiss wrote a Jewish legal analysis explaining why women are permitted to read the scroll in 1998.

“I personally am someone who advocates, and in our synagogue community looks to expand, women’s roles and give more opportunities for women,” said the synagogue’s current senior rabbi, Steven Exler.

Lewin is also watching the practice expand at her synagogue, Washington, D.C.’s Kesher Israel Congregation, where women have read from the Megillah for nearly three decades. This year, she’s reading the fewest chapters of the Megillah she has ever read. She usually reads half of the scroll, including a difficult passage in the ninth chapter. But for this week’s women’s reading at her synagogue, a new volunteer signed up to chant the ninth chapter.

Still, despite her pioneering reading at age 12, and her decades of chanting, Lewin has encountered the Orthodox community’s ambivalence around women and Megillah firsthand. For many years, she borrowed her father’s scroll when Purim came around. But about eight years ago, Lewin asked him for her own scroll as a gift, which can cost upwards of $1,800.

Lewin’s father traveled to Israel to find a scribe to commission the Megillah. But he wasn’t comfortable telling the scribe the Megillah would go to a woman, and instead said it was a gift for his son-in-law.

Years later, Lewin was at a wedding where she met the scribe who wrote her treasured Megillah, and revealed to him that the scroll belonged to her.

“He was thrilled,” Lewin said. “I think it was his individual personality. There are some individuals who are very supportive of the increase in opportunity for women, that women are becoming much more learned in terms of Jewish law.”