The story of Balaam and his talking donkey is a major problem for serious theologians and scholars of the Bible. If you are not familiar with this gem in this week’s Torah portion, take a look at Numbers 22:20-25, the story that contains the chattering mule. Some people poke fun at literalists who believe that the donkey actually spoke. These literalist might point to a fish called “sarcastic fringehead” (neoclinus blanchardi) and say that if this denizen of the shallow exists, why not the talking donkey starring in this tale saturated with irony (if not sarcasm).

In case you are not caught up on your Bible stories, here is a quick summary. The King of Moab is terrified of the Israelites. They began their march across the Sinai desert to Canaan and seemed undefeatable, the Mike Tyson of their times. The scared King engages a certified prophet of God, Bilaam, to curse the Israelites, and offers a substantial reward. Bilaam, takes the challenge, but says he must ask God. After some initial resistance, Bilaam finally got God to “yes,” with the caveat: ‘Only say what I tell you to say.”

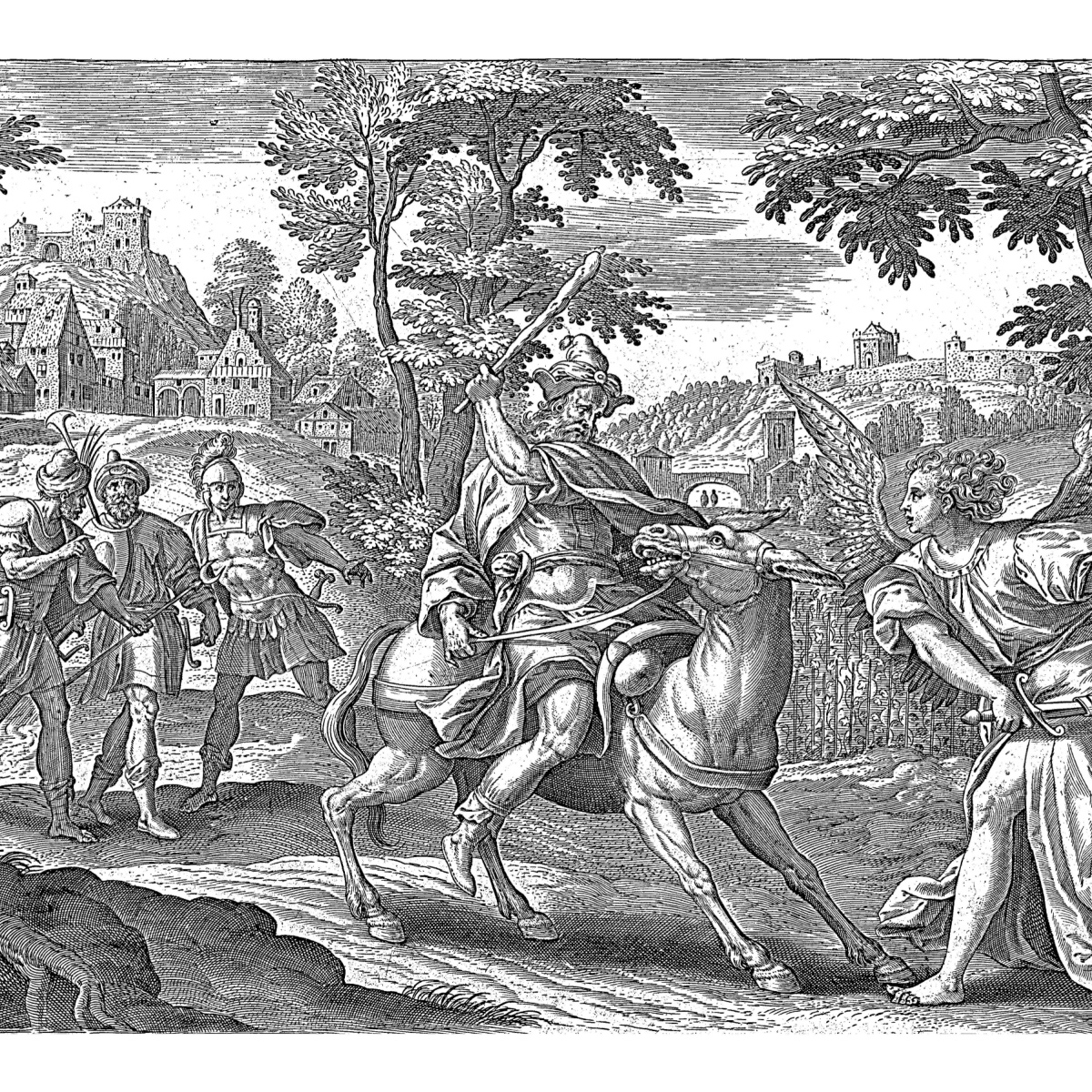

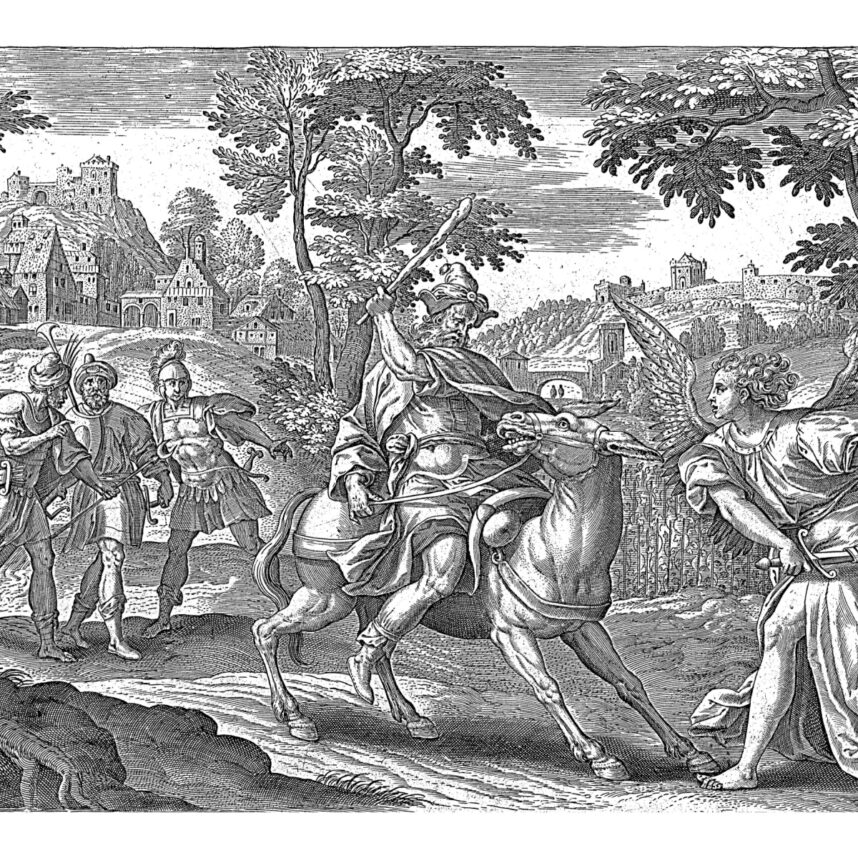

The prophet alights upon his donkey. Somewhat inexplicably, God becomes angry. Suddenly a fierce sword wielding angel appeared on the road, but only to the donkey, not to the prophet. The donkey veered off the path to avoid the sword and the angel. Bilaam beat the donkey to get her back on the road, but the angel cornered the donkey and her rider. The donkey, offended at having been beaten, speaks up and says something like, “I’ve worked for you a long time; have I ever done anything this before?” I imagine the donkey urgently gesturing with her ears trying to say, “There’s something on the road you need to know about!” The angel finally reveals himself, also angry that Bilaam had beaten the donkey. The angel tells Bilaam that he came down to kill him, but the donkey saved him. Bilaam apologizes and offers to go back; the angel tells him to go on, but remember: “Say only what God tells you to say.”

We, the readers, can only infer that Bilaam was daydreaming about the curses he wanted to cast upon the unsuspecting Israelites, camping on the other side of the hill yonder, to please his patron the king, but God caught him. “How did He know what I was thinking?” Bilaam probably asked himself, but then quickly answered his own question. “Right. God.” The remainder of the story is an exquisitely written farce.

Full disclosure: I see the Bible as literature, not journalism. Great literature contains jokes. This passage is burlesque satire, meant, in my mind, to make us laugh, think and admire. If you’ve never read the Bible before, you absolutely for sure did not see this story coming.

Serious theologians avoid the embarrassment of this passage by taking it utterly seriously. Theologians, such as the greatest Jewish theologian, Maimonides, file this passage under “prophecy,” not “the best jokes in the Bible.”

Prophecy is almost certainly the most important idea in medieval Jewish theology. Medieval philosophers, under the powerful sway of Plato and Aristotle, saw the Bible as we might see a dream – fantastic metaphors for the uninitiated, metaphors aimed at communicating truths, almost too unbearable for us to know.

For example, you might upon awakening say, “There I was, walking in the mud of the low tide, and suddenly I was surrounded by sarcastic fringeheads nipping at my feet!” You weren’t actually surrounded by sarcastic fringeheads; your dream factory took some object of your unconscious, your insufferable teenager, for example, and created a metaphor to communicate a thought.

Powerful truths are communicated to simple people through metaphors, according to the medieval theologians. ‘God spoke to the people’ and ‘God descended on Sinai in fire and smoke,” are obviously impossible for a God of pure being that does not have vocal cords, nor a corporeal body at all that can move from place to place.

Those initiated into divine secrets look past the metaphors and ask a fundamental question: how can a God of pure being communicate with human beings? Who can know the secrets of the Divine realm, and how? Why some people and not others? Closer to our Torah portion, how can we explain that a person such a Bilaam, who appears to be an archetype of inauthenticity and lack of integrity, is called a prophet?

The theories of mystical experience and accessing knowledge of the Divine devised by the medieval theologians are truly stunning and piercing works of brilliance. I’d like to talk about some of these theories Friday night, after a I deal with a question I can’t let go of.

The scene of this story is on the other side of a hill far away from the Israelites. Who leaked this story of Bilaam’s crushing reckoning with God? The only ones who knew were Bilaam, God, the Angel – and the donkey. Was there a Donkey Night at the Comedy Club of Canaan? And even then, how did this story get into the Bible?

If this is a Divine secret, I want to know it.