Following a yearlong, $14.5 million renovation, the Jewish Museum — which is housed a 1908 French Gothic mansion on Fifth Avenue — is opening two upgraded floors to the public.

Among the new features on the museum’s reimagined third and fourth floors: a new installation, “Identity, Culture and Community: Stories from the Collections of the Jewish Museum,” which spotlights 200 items from the museum’s permanent collection; four galleries for rotating exhibits and new acquisitions and the Pruzan Family Center for Learning, featuring art-making studios, a touch wall, and an interactive, simulated archaeological dig.

The renovation is the brainchild of the museum’s director, James Snyder, who assumed the helm of the 121-year-old institution in November 2023, following stints as the director of the Israel Museum and deputy director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The renovation “gave us the opportunity to think through an entirely new narrative, an entirely new strategy for what we are all about,” Snyder said during a press event on Tuesday.

“These are complex times — they have been for a while. They’re getting more and more complex every day,” Snyder said. “Our job, particularly for culturally specific museums like this one, is to be the antidote to what’s really a pandemic today — to the xenophobia, the racism, the ignorance that is prevalent everywhere now.”

Here are seven things to see and do at the renovated Jewish Museum’s new galleries.

1. Marc Chagall’s “Self-Portrait with Palette” (1917)

Marc Chagall’s “Self-Portrait with Palette” (1917) is among the new acquisitions at the Jewish Museum. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

This self-portrait by the lauded Jewish artist is in the Cubist style. An oil on canvas, the painting shows Chagall as a young man holding a brush and palette, with his hometown of Vitebsk (in today’s Belarus) in the background.

When the portrait was painted — during the Russian Revolution — Chagall had just returned home after three years at a Parisian art school in order to marry his childhood sweetheart, Bella Rosenfeld, who modeled for many of his works.

The painting, a new acquisition by the museum, was previously in a private collection. It was last publicly exhibited at the Tefaf New York art fair at the Park Avenue Armory in 2022. It hangs “in conversation” with a newly acquired piece by Alice Neel, titled “Nazis Murder Jews,” from 1936, an unusually non-abstract work by Mark Rothko that shows a deconstructed crucifix, and three paintings by Romanian-Israeli painter Reuven Rubin.

2. 130+ Hanukkah lamps, from ancient times to the present

A glass case of more than 130 Hanukkah lamps is part of the Jewish Museum’s identity and culture exhibit, drawn from the museum’s collection. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

The Jewish Museum has more than 1,400 Hanukkah menorahs in its collection, and as part of its new, fourth-floor learning center, more than 130 are on display in a space that is open to a double-height gallery on the third floor.

The installation — featuring menorahs from across the globe, antiquity to the present day — is meant to accentuate “the central meaning of light as a symbol of enlightenment and hope across cultures,” per a press release.

Particular highlights include oil lamps from the 2nd to 1st century BCE, as well as a “Menurkey” — a turkey-shaped menorah, devised by 9-year-old Asher Weintraub in 2013, when Thanksgiving and Hanukkah overlapped for the first time since 1888.

3. “The Return of the Volunteer from the Wars of Liberation to His Family Still Living in Accordance with Old Customs” (1833–34) by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim

‘The Return of the Volunteer from the Wars of Liberation to His Family Still Living in Accordance with Old Customs” by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim. (Courtesy The Jewish Museum)

Considered to be the first Jewish painter in the modern era, Moritz Daniel Oppenheim — born in 1800 in Hanau, Germany — is known for being the first Jew to receive a formal arts education in Europe.

Many of Oppenheim’s works — which are on view at the museum as part of its permanent collection — showcase intimate portraits of Jewish life in Europe. Considered his masterpiece, “The Return of the Volunteer,” depicts a young German Jewish man returning home after helping defend Germany against the Napoleonic armies just as his family is welcoming Shabbat. (Note the challah and kiddush cup on the table.)

Oppenheim created the painting during a time of civil unrest following the 1830 revolutions in France, when some German states passed repressive legislation against the Jews. Per the Jewish Museum, “This painting has been interpreted as a reminder to Germans of the significant role played by Jews in the Wars of Liberation, and its political overtones are unusual in the generally apolitical nature of Biedermeier art.”

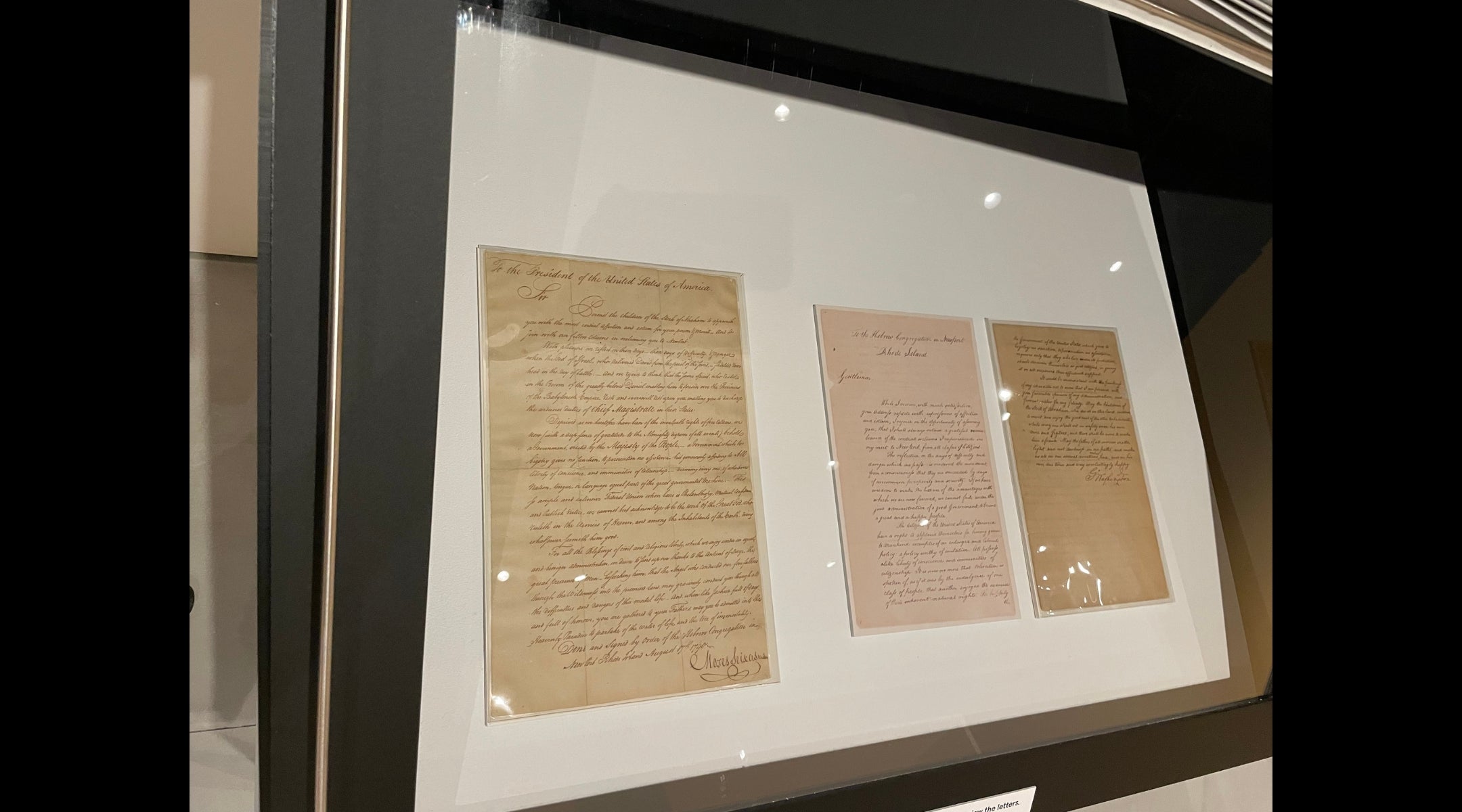

4. Letters between George Washington and Moses Seixas

A letter exchange between Touro Synagogue president Moses Seixas and American President George Washington. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Part of the new “Identity, Culture and Community” exhibit is a section on Jews in the Colonial Era. A highlight here are letters from 1790 between new American President George Washington and Moses Seixas, the president of Jeshuat Israel of Newport, Rhode Island, now known as the Touro Synagogue — the oldest synagogue in the United States.

Washington came to Rhode Island after the state ratified the United States Constitution in order to promote the passing of the Bill of Rights; upon Washington’s arrival in Newport, Seixas read a letter aloud to the president, in which he expressed optimism at the freedom of religion that Americans would see in this new country.

“May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants —,” Washington wrote in response, adding a quotation from scripture, “while everyone shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

The letters are so delicate they’re kept under a window blind that visitors manually pull up and down, to minimize exposure to light.

5. A child-friendly mock archaeology dig

Visitors of all ages can dig for replicas of real ancient artifacts in the Jewish Museum’s newly renovated dig room. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

As part of the Pruzan Family Center for Learning, the Jewish Museum’s new mock archeology dig is three times larger than the previous version. Here, as part of the visitors can dig through four pits, each centered around a different era in time, for replicas of real artifacts, such as an Ottoman-era copper alloy coffeepot from Jerusalem, an ancient Roman oil lamp and a calcite-alabaster jar from ancient Egypt circa 1550 BCE.

The real versions of those artifacts — most of them newly on display in the room — are also on display, accompanied by kid-friendly language. Families are provided with an “Archaeologist’s Notebook” to keep track of their finds.

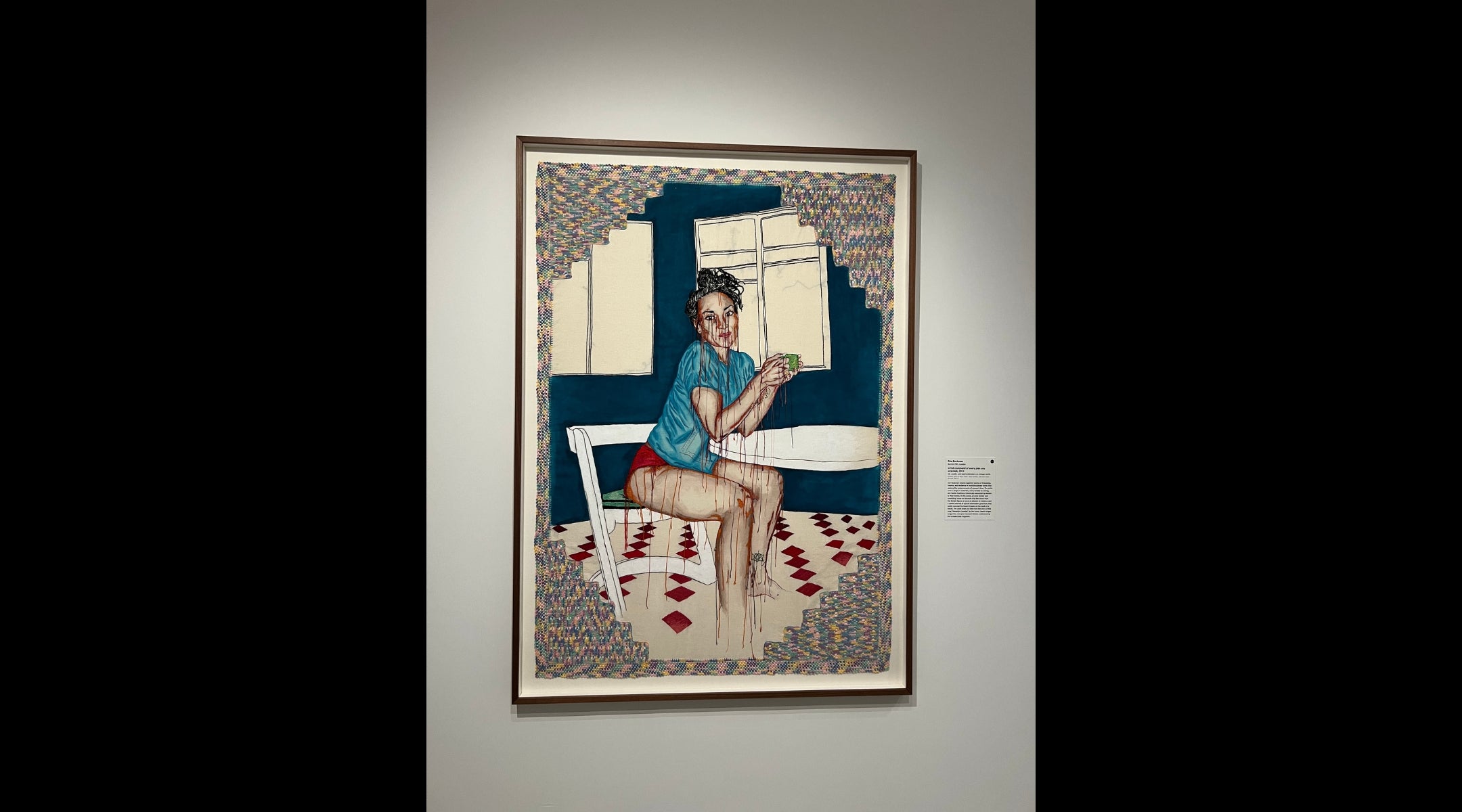

6. “in full command of every plan you wrecked” (2024) by Zoë Buckman

“in full command of every plan you wrecked” by Zoë Buckman is on view at the Jewish Museum as part of the third floor’s rotating exhibitions. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Zoë Buckman, 40, is a British Jewish artist whose work has been featured in the UK’s National Portrait Gallery and who has emerged as a prominent voice among artists on antisemitism in the wake of the Gaza war. This ink, acrylic and hand-embroidered piece is Buckman’s debut at the Jewish Museum, which is part of her “Who by Fire” series exploring Jewish personhood.

Located on a third-floor gallery, Buckman’s work depicts a woman sitting on a chair; the piece’s name, “in full command of every plan you wrecked,” a reference to a Leonard Cohen lyric from “Alexandra Leaving.” The loose threads — typically found on the back of such woven pieces — subvert expectations of traditional feminine and domestic textile work.

7. A retrospective on the early works of Anish Kapoor

Some of the early sculptural pigment works of Anish Kapoor at the Jewish Museum. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Born in India in 1954 to a Punjabi Hindu father and an Iraqi Jewish mother from Mumbai, Anish Kapoor rose to prominence as an artist exploring matter, non-matter, space and voids. “Anish Kapoor: Early Works,” on view until Feb. 26, 2026, is the first American museum presentation showcasing Kapoor’s works from the late 1970s and early 1980s, “when he was still the classic starving artist,” per the New York Times.

Snyder and Kapoor — a winner of the prestigious Genesis Prize — have previously collaborated on exhibits at MoMA and the Israel Museum; the Jewish Museum exhibit opens on Friday alongside the museum’s newly reimagined floors. “He is about this narrative of the experience of the Diaspora and what it does to artists,” Snyder said of Kapoor.

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.