The Kuzarim. Their very name recalls wonderful tales of a people we know little about but who have nonetheless left a lasting impression on Jewish history, folklore, identity, and, most conspicuously, literature.

The Khazars were a semi-nomadic people who lived from the 7th to 10th centuries in what is today southwestern Russia and converted to Judaism. They first appear in Jewish literature in the introduction to Emunot Vedeot by R. Saadia Gaon (he mentions them in passing), but Muslim and Christian sources already in the 9th century mention the Khazars as a people observing Jewish law.

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 0 });

Some time between 954 and 961, Hasdai ibn Shaprut – a leader of the Jews in Muslim Spain – wrote a letter to the ruler of the Kuzarim and received a reply from “Yosef of Khazaria” in which the Kuzarim’s conversion to Judaism is described as coming after a debate between Jewish, Muslim, and Christian representatives in front of the Khazarian king.

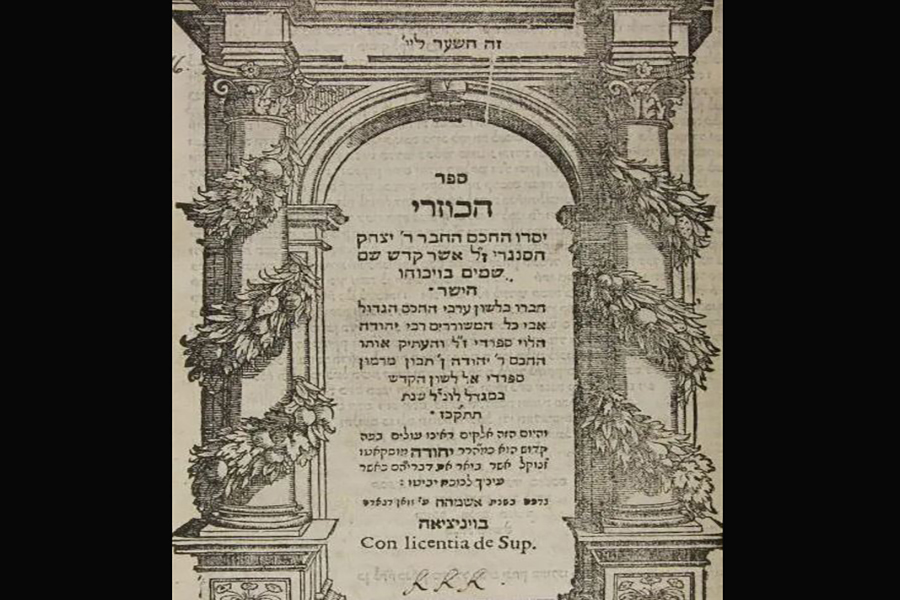

Several sefarim “reenacted” this debate, using it as a platform to prove the authenticity of Judaism. The first and most well-known of these sefarim is Sefer Kuzari, written by R. Yehuda Halevi around the year 1140. The book is written in the form of a dialogue between the king of the Khazars and representatives of the three Abrahamic religions on matters of faith.

In a letter (found in the Cairo Genizah), R. Yehudah Halevi wrote to a colleague that he wrote his work in response to questions sent to him by a Karaite philosopher.

Though originally written in Arabic, the work was soon translated to Hebrew and is best known by its Hebrew name, Sefer Kuzari. This work was an immediate success, and many commentaries have been written on it. The Vilna Gaon is quoted as saying, “One should study Sefer Kuzari, as it is holy and pure and the fundamentals of Jewish belief and Torah are dependent on it.”

The Second Kuzari

The second work to use the Khazar debate to defend Judaism was Kuzari Sheni by R. David Nieto (1654-1728). Nieto served as the rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community in London, and his work was written in both Hebrew and Spanish. Published in 1714, Kuzari Sheni defends Torah Sheba’al Peh against arguments of the Karaites and later heretics.

The second work to use the Khazar debate to defend Judaism was Kuzari Sheni by R. David Nieto (1654-1728). Nieto served as the rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community in London, and his work was written in both Hebrew and Spanish. Published in 1714, Kuzari Sheni defends Torah Sheba’al Peh against arguments of the Karaites and later heretics.

His intended target was most likely contemporary Jewish heretics, particularly Uriel Acosta who was put into cherem by the Hamburg Jewish community. Nieto viewed his book as a continuation of the Kuzari of R. Yehuda Halevi and was an active defender of Judaism against the arguments of free-minded former Marranos who served as a major threat to the Western European Jewish communities at the time.

In Kuzari Sheni, Nieto methodically demonstrates that the Talmud and Mishnah never veer from the written Torah; they only elaborate and explain the original text. Nieto made use of fictional as well as historical Karaite spokesmen in an effort to bolster his arguments and refute the claims of the heretics of his day.

The Third Kuzari

In 1905, a book titled Kuzari Shlishi (the third Kuzari) was published in Munkatch; its author was Rabbi Mordechai Dickman. An enigmatic character of Galician origin, Rabbi Dickman moved shortly after writing this work to Toronto where he is recorded as being the first shochet of the city. (A later edition of Kuzari Shlishi was the first Hebrew book published in Toronto.)

This fascinating sefer – like the first two Kuzaris – is written in the form of debate. Participants in it include the Emperor Franz Joseph; representatives of many of the great world powers, including Spain, France, Russia, Egypt, Germany, and Japan; representatives of many of the popular ideologies of the time, such as communism, socialism, and capitalism; and, of course, a Jew representing Torah Judaism.

This fascinating sefer – like the first two Kuzaris – is written in the form of debate. Participants in it include the Emperor Franz Joseph; representatives of many of the great world powers, including Spain, France, Russia, Egypt, Germany, and Japan; representatives of many of the popular ideologies of the time, such as communism, socialism, and capitalism; and, of course, a Jew representing Torah Judaism.

Rabbi Dickman prefaces his book by addressing the Hungarian Jews amongst whom he lived at the time, arguing that they are best suited to gain from his book since they are by nature G-d fearing. He contrasts them with the Jews of his native Galicia, who, he writes, are already too lost for a philosophical tract defending Judaism to be of any use.

The author had great hopes for his Kuzari Shlishi, believing it would help defeat the assimilation and apathy of Jews of his day.

The New Kuzari

R. Isaac Breuer (1883-1946) – a German Orthodox rabbi, grandson of R. Samson Raphael Hirsch, and the first president of Poalei Agudat Yisrael – wrote The New Kuzari in 1934 in response to changing dynamics in Germany and Palestine. It was written in German under the title Der Neue Kusari and has been recently translated into Hebrew.

This work, in the form of a dialogue between a young German Jew, Alfred Roden, and a number of other people representing various ideologies (including Reform Judaism and Zionism), covers a variety of philosophical and ideological topics, including Orthodox Judaism’s approach to the Zionist movement.

This work, in the form of a dialogue between a young German Jew, Alfred Roden, and a number of other people representing various ideologies (including Reform Judaism and Zionism), covers a variety of philosophical and ideological topics, including Orthodox Judaism’s approach to the Zionist movement.

Although Breuer, following in the footsteps of his grandfather, originally opposed Zionism, in his New Kuzari, he developed his “Torah Im Derech Eretz Yisrael” philosophy, which calls for rebuilding Eretz Yisrael as a halachic state. He believed doing so was an obligation upon every Jew at that point in history.

He also utilizes Kantian philosophy in discussing the nature of belief and proof in Judaism. Breuer greatly admired Kant and is said to have had a portrait of Kant alongside his grandfather, R. Samson R. Hirsch, in his study.

<!–

Publisher #16: JewishPress.com

Zone #113: Comment Banner / (02) / News

Size #15: Banner 468×60 (Comments and Mobile) [468×60]

–> ‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 25 });