On the surface, New York-based filmmaker Yael Melamede’s latest documentary is an intimate story about her mother, award-winning Israeli architect Ada Karmi-Melamede.

Ada, 88, who was born Mandatory Palestine and comes from a family of architects, is renowned for creating some of Israel’s best-known public buildings, including Ben-Gurion Airport, the Ramat HaNadiv Nature Park Visitor’s Center and, perhaps most notable of all, Israel’s Supreme Court building in Jerusalem.

While “Ada: My Mother the Architect” pays tribute to Ada’s world-class creations — she won the Israel Prize for Architecture in 2007, like her father and brother before her — the film is also about so much more. Although Ada’s musings on what makes beautiful buildings are both thought-provoking and entertaining, the film is a subdued yet deeply moving meditation on family, the nature of “home,” the challenges working mothers face and, perhaps most of all, the sadness that many Israelis feel about the direction the country is taking. (Filming wrapped in the summer of 2023 as Israel erupted in protests over Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s attempts to curb the power of the Supreme Court.)

“Doing a film about my mother was a way for me to explore my relationship to Israel,” Yael said during a Zoom interview Thursday from her Manhattan home. “I loved the idea of kind of talking about a place indirectly — not about whether it’s good or bad, or right or wrong, but a much more complex story through their perspective.”

New York City-based filmmaker Yael Melamede. (Courtesy)

In the film, Ada describes how the notion of “roots” forms the backbone of her architectural ideology. “There are buildings that have roots,” she says. “They hit the ground, penetrate it, and take root. You sense that this attachment is a very important part of architectural thinking, because these buildings belong to the place.”

Ada’s roots, Yael explains, are in Israel, where her mother has lived alone for more than 40 years — and where she continues to commute to her Tel Aviv office daily.

Yael, meanwhile — 57 and the youngest of three children — was born and raised in Manhattan. The family had moved to New York in the 1960s for her father’s business career; the initial plan was to live here a few years and then return to Israel. Instead, though, the Melamedes remained in New York. Here, Ada spent 14 years teaching architecture at Columbia University, where she also worked on large-scale urban initiatives like a master plan for Con Edison and a study for the proposed Second Avenue Subway.

When Ada was passed over for tenure at Columbia, she returned to Israel to work alongside her brother, architect Ram Karmi, who was well known for his Brutalist style, and her career took off. In 1986, the siblings entered and won a competition to design the Supreme Court building. The project — which New York Times architecture critic Paul Golberger, who appears in the film, described as “a work of considerable subtlety and complexity, so much so that my first thought upon seeing it is not how good it is for Israel, but how sad it is that public architecture in the United States is rarely as thoughtful, and rarely as skillful in combining a sense of monumentality with a sense of easy, inviting accessibility” — came with the stipulation that Ada leave Israel for only a few weeks each year.

And so Ada stayed in Israel, while her husband Amos and their children remained in New York.

“Maybe I’m not much of a Jewish mother,” Ada says in the film, when asked about how she handled the distance from her family. “I never really worried about you.”

Yael, in conversation with the New York Jewish Week, as in the film, said she doesn’t view the long-distance relationship with her mother with sadness, nor is a tearful goodbye seared in her memory. “Nobody in my family remembers when she left — she doesn’t remember when she left,” she said. “She was spending a little more time in Israel, and then she was spending a little bit more time, and then they were invited to the competition, and then she was just there.”

In spite of the physical separation, the film shows a palpable closeness between mother and daughter, who switch seamlessly between Hebrew and English. “I think we have a really beautiful relationship,” Yael said. “There’s tons of love between us, but I do think we have an unusual mutual respect. We don’t have a lot of garbage in our relationship.”

She added: “I think she gave me a real gift as a woman, and as a mother, about not ever feeling guilty about working. I didn’t realize how special that was.” (Yael’s son, Niv, who had Type 1 diabetes, tragically died at age 22 near the end of filming “Ada: My Mother the Architect.”)

It’s possible that mother-daughter even share a similar sense of purpose when it comes to their work. “The role of the architect is to figure out how to work between all the different elements to make something that’s good for everyone,” she said. “That’s the Middle East right there. It’s family, it’s home, it’s politics, it’s about figuring out a better way to live more consciously, more communally.”

Ahead of the theatrical release of “Ada: My Mother the Architect” at the Angelika Film Center, Yael chatted with the New York Jewish Week about motherhood, creating art, building buzz and how this film might challenge audiences’ perspectives on Israel.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited.

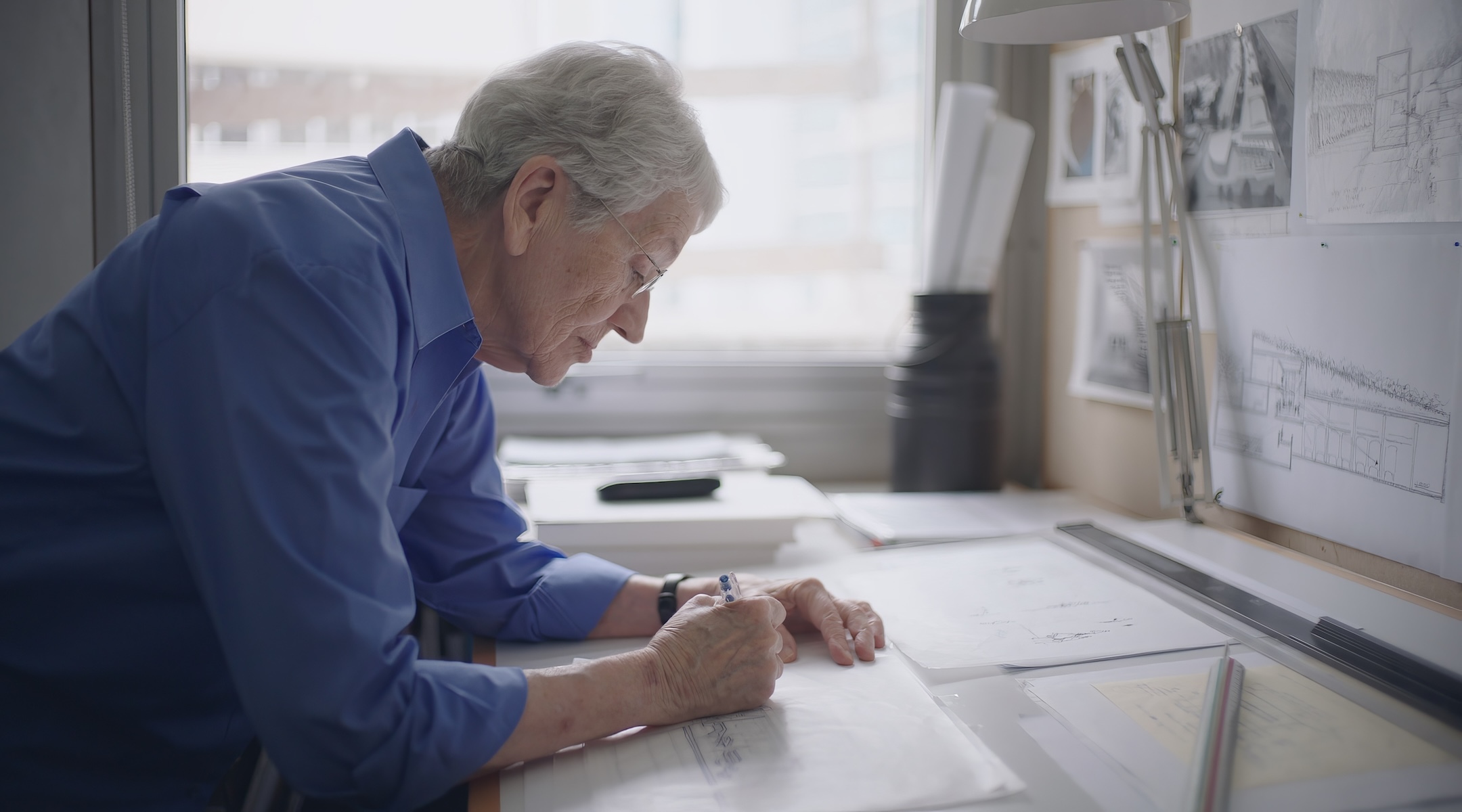

Israeli architect Ada Karmi-Melamede in her Tel Aviv office. (Courtesy Salty Features)

What inspired you to make this film about your mother?

It wasn’t like I went into this project knowing what it would be. I just had this feeling that she was really interesting and very mysterious to most of the world — like I know her so well, but other people didn’t, and I felt like she had something really special to offer in this kind of quiet power. I think she’s so strong in a certain way, and so reserved. And I have an interest in people who are really passionate about their work, like they see all of life’s mysteries in that endeavor.

I thought she was really interesting, but I didn’t know how to approach it. It took a long time, and the process of making the film really taught me how to make it … the kind of balance between architecture and [the] personal, I really just knew nothing going into it other than I thought there was something really special there.

You mentioned how making a film about your mother was an avenue to explore your relationship to Israel. How would you describe that relationship?

I think it is a place of such extraordinary beauty and talent and innovation and energy. There’s something about the energy of Israel and Israelis that I love so much, but it’s within a context that is becoming increasingly tragic from within and without.

The other part that I never expected was that the problems that Israel is having would somehow start to be translated into problems we’re having in my primary home, that issues that Israel is facing are issues that we are now facing [in the United States].

Did you learn anything surprising while making the film?

I knew my mom was a really good teacher, and the students liked her. I had no idea the depth to which students loved her. But there are so many, and the letters that we’ve gotten since the film was finished about what an impact she had as a teacher has been astonishing, really, really astonishing. I didn’t think of that legacy being so strong.

I see you’re hosting a series of post-screening Q&A sessions at the Angelika, featuring a wide variety of special guests, including architecture critic Paul Goldberger, Lab/Shul’s Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie and architect Billie Tsien. How did this come about?

The independent film business, which I am squarely a part of, is kind of in shambles. It’s really hard to get films out — any films — and a film that has any Israeli content in it whatsoever is even harder. But one of the ways that independent films try to distinguish themselves is by creating interesting conversations around them. I love the Q and A’s that we’re doing, because they’re coming from many different perspectives.

What do you hope audiences will take away from the film?

I wish that people who had preconceived notions about Israel would watch the film in order for those notions to be a little bit — shattered is not the right word — moved or changed. And then, I think it depends on the person, I’d love for people to think about architecture and about Israel and about motherhood and family in a different way, in a more nuanced way, and to move away in all of those areas harsh judgments of good and bad, right and wrong, and more. You know, how can we live our healthiest lives in the healthiest places, in the healthiest ways.

“Ada: My Mother the Architect” is screening at the Angelika Film Center (18 West Houston St.) on Thursday, May 8. For tickets and more details, click here.

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.