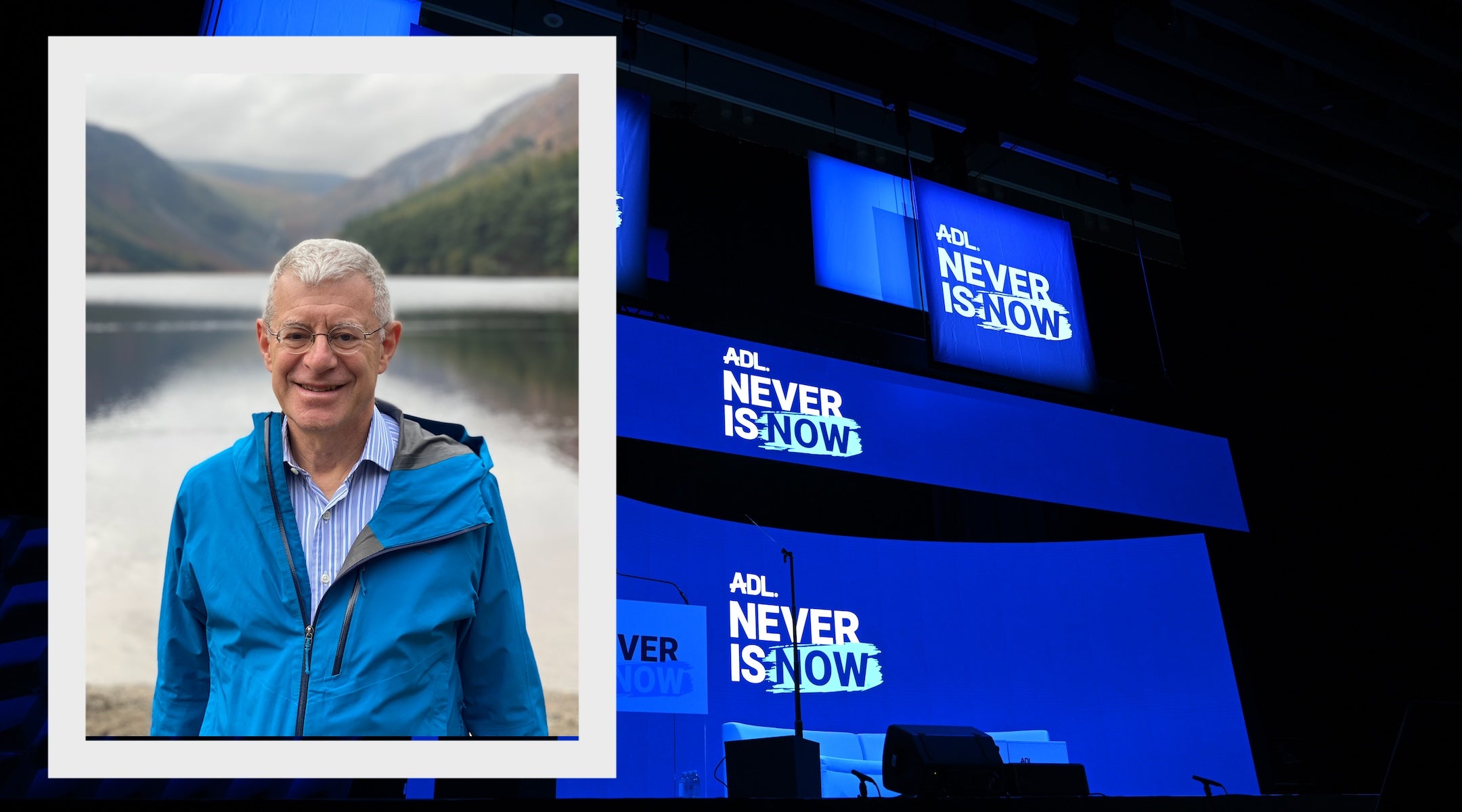

The former top litigation volunteer at the Anti-Defamation League is making public his scorching resignation letter from the group, in the latest sign of Jewish discontent over the organization’s shifts during the second Trump administration.

Joe Berman, who chaired the ADL’s National Legal Affairs Committee from 2018 to 2022 and who volunteered in other capacities until this year, said in an interview he left because the venerated civil rights group had become a “useful idiot” for the Trump administration by failing to respond aggressively to antisemitism on the right.

“Whether intentionally or ignorantly, ADL is providing cover to people who intend great harm to our nation,” Berman said in his letter resigning from two national and one regional leadership bodies. Berman sent the letter in March and is making it public now for the first time through the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Voicing a perspective that is common among liberal opponents of Trump, Berman argued that the Trump administration has used the pretext of alleged antisemitism to impose penalties on universities and arrest non-citizens.

“Jews and the fight against antisemitism are being cynically used to advance an authoritarian, anti-democratic agenda,” he wrote. “For ADL’s national leadership to not recognize these clear and present dangers is inexplicable.”

Berman added, ”Make no mistake: this will not end well, especially for Jewish Americans.”

In a response to Berman’s letter, an ADL spokesperson reiterated the argument that CEO Jonathan Greenblatt laid out in a recent op-ed: that during a time of dramatically increased antisemitism, shifting focus and resources away from other societal challenges is only appropriate.

“The shocking rise of antisemitic violence in recent years — from Pittsburgh to Poway, from Boulder to Washington, D.C. — has required us to intensify our focus on protecting the Jewish people,” the spokesperson said. “The Jewish community is facing an ‘oxygen mask moment.’ We do not have unlimited resources, and we must make choices about priorities. While we cheer on those working to protect civil rights for other groups, we are focusing our time, energy, and money on the fight against antisemitism.”

The ADL is the largest advocacy organization by far in the world dedicated to fighting antisemitism. Its statistics are widely cited, and its operations include not only advocacy and litigation but monitoring extremism and advancing research about the causes of antisemitism.

While it enjoys broad support in the Jewish community, the ADL has many critics on both the left and right. Berman’s broadside is the latest expression of unhappiness with the fundamental changes under Greenblatt, under whose leadership the organization’s focus has narrowed to just fighting antisemitism and anti-Zionism.

Among other shifts roiling Berman and other onetime supporters of the group are the shuttering this year of a profitable anti-bigotry training program, “World of Difference,” the scrubbing from its websites of references to its civil rights advocacy, and the reshaping of its storied civil rights litigation unit into one targeting only antisemitism. They say the organization has given up its alliances with other groups — and with it its standing in the civil rights space.

Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan Greenblatt speaks at the group’s 2018 National Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C. (Michael Brochstein/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

“We stood up for the LGBTQ community, for the African American community, for immigrants, and it was a real core part of our mission,” said Berman, who also served from 2020 to 2023 as the chairman of the ADL’s New England regional board. “And our [legal] briefs were just incredible. And we would often do it in coalition with other civil rights groups, and that’s all gone. That respect that we had is just completely gone.”

Berman is not the first ADL affiliate to resign in frustration this year over the changes: The Forward in June reported an equally scathing resignation letter by Steven Ludwig, a member of the Philadelphia regional board.

More recently, (JEWISH REVIEW) spoke to 11 former staffers, contractors and lay leaders or volunteers for the ADL, some who are ready to go on the record for the first time. They all say they had for years been discomfited by the organization’s shift away from its broad civil rights mission, a change that accelerated after Oct. 7, 2023, when Hamas’ attack on Israel and the subsequent explosion of antisemitism spurred Greenblatt to openly declare a narrowed focus.

Stacy Burdett, who served as the Washington-based vice president of government relations for the ADL from 1993 to 2017, would not comment on the group’s trajectory, but she said that the group’s mission had long been twofold — and that both prongs served American Jews.

“Since Lincoln’s administration, American Jewish advocacy has been rooted in the idea that protecting Jewish rights and all civil rights was both a strategic and moral imperative,” she said in an email. “Separating them harms both of those objectives. The surge of civil rights advocacy from rabbis and Jews all over the country belies the notion that they have to choose. To them, the two are inextricable.”

Greenblatt initially embraced that outlook when he succeeded Abraham Foxman as the ADL’s CEO in 2015, writing in a 2017 coffee-table book, “The Good Fight,” that the century-old group had widened its purview beyond antisemitism soon after its founding.

But a few years into his tenure, people who worked at the organization recall, cracks began showing.

Jason Sirois, who was from 2018 to 2021 ADL’s national director of education programs, said he tracked with dismay the diminishment of the ADL’s flagship anti-bigotry training programs for schools, known as World of Difference, which was unique in emphasizing holistic anti-bigotry training, as opposed to emphasizing the targeting of a single vulnerable population. ADL shuttered the program earlier this year, a development first reported by the left-wing magazine Jewish Currents.

“In all of the research they did, one of the things they found is a majority of people were invested in ADL because of education, and yet it always felt very much like it was taken for granted,” he said in an interview. “It was not invested in even though we were revenue-generating and covered our own expenses.”

The ADL spokesperson said education was still a key part of ADL’s mission, although he emphasized education to counter antisemitism, as opposed to the holistic approach taken by World of Difference.

“The continued growth of our education work is significant, delivers interventions on fighting antisemitism, educating on the Holocaust, and addressing bias in schools in a way that schools want, and is scalable,” the spokesperson said, “meaning we can reach more students, educators and schools than ever before as college and K-12 students and educators face an unrelenting barrage of antisemitic in the classroom and on campus.”

Melanie Robbins, who worked in the New York and New Jersey regional offices from 2016 to 2019, eventually rising to deputy director, recalled what she characterized as a milestone in Greenblatt’s shift. She said he appeared furious after the ADL was lacerated from the right when it opposed President Donald Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court in 2018, citing his record on reproductive rights. One critique, as outlined by the conservative Jewish commentator Liel Leibovitz in the Wall Street Journal at the time, was that the ADL was ceding its mission of protecting Jews “by weighing in on matters far removed from its traditional mandate.”

The ADL as a matter of course filed amicus briefs on abortion rights cases. “ADL has filed amicus briefs in every major Supreme Court case since Roe supporting reproductive freedom and opposing efforts to curtail abortion rights,” the group said in 2019, explaining why it regarded defending abortion as a matter of discrimination and curtailing hate.

After the op-ed, Greenblatt responded strongly, recalled Robbins. She said he erupted at a meeting with the regional office’s executive board. “Jonathan came and he was very angry. He said women’s issues are not core issues,” she said in an interview. She said he was yelling. Another former staffer recalled a similar encounter with Greenblatt about the ADL’s Kavanaugh statement.

The ADL spokesperson did not deny the account, but said reproductive rights were never front and center for the organization and the Kavanaugh confirmation had no effect on the group’s policy.

“While ADL has a policy position on Reproductive Rights, ADL is not and has never been a reproductive rights organization,” the spokesperson said. “We have always let other organizations lead on this issue since they are far better equipped, knowledgeable, and focused on this issue.”

Meanwhile, the disbanding of the ADL’s Civil Rights Law team, including the departure in the first years of this decade of lawyers like Michael Lieberman, who was instrumental in the passage of federal hate crime laws, has alarmed some of the lawyers who once contributed briefs pro-bono. (Lieberman declined a request for comment.) They say the group has erased their work from a major search engine for amicus briefs, which no longer yields results for ADL briefs, though many can be found elsewhere online.

ADL’s litigation now emphasizes antisemitism, replicating the mission of other groups such as the Brandeis Center.

The cost to Jews of the changes is steep, Berman said.

“There really isn’t another Jewish organization that has the mission that we did. Now it seems as if the Jews are separate from all of that. And that is to our detriment,” he said.

Berman added, “When you don’t work on with other groups, then you’re not going to have those other groups come into your defense. And that was the whole basis. It’s gone now.”

For him, the point of no return came earlier this year when the ADL endorsed immigration authorities’ arrest of Mahmoud Khalil, a permanent resident who was an organizer of anti-Israel protests at Columbia University.

“We appreciate the Trump Administration’s broad, bold set of efforts to counter campus antisemitism — and this action further illustrates that resolve by holding alleged perpetrators responsible for their actions,” the ADL said at the time of the arrest in March.

Berman viewed the response as a clear compromise on core values that could ultimately harm Jews. Khalil’s “detention is a clear violation of the Constitution,” he wrote in his resignation letter adding that Khalil’s views were “disgraceful” but protected speech. “For ADL to not recognize these basic and obvious points is baffling.”

More recently, the ADL has raised eyebrows by not commenting on topics that would have drawn its censure in the past, including, notably, Trump’s recent attacks on Somalis in Minnesota.

“The current pivot is to solely fight antisemitism, to abandon allyship and to remain silent when other minorities are targeted,” Ludwig said in a text. “If it only matters now to ADL that Jews are safe and to be silent when many others are not, that is at best shortsighted.”

Nearly nine months after resigning, Berman, who is the general counsel of the Massachusetts Supreme Court Board of Bar Overseers, said he still feels pain over having felt forced to do so.

“ADL has been a big part of my life since the mid-1990s, so it was really difficult for me to leave,” he said. “One of the things that I really loved was the dual mission, the protection of Jews, but also advancement of civil rights, and how those two were symbiotic. You really can’t have one without the other.”