(JTA) — Jesse Wilks had a bar mitzvah — just not a religious one.

His parents raised him in a secular home in New York City but still instilled him with a strong sense of Jewish identity. His mother — who worked for the Workers Circle and is now on the editorial board of the left-wing Jewish Currents magazine — hosted holiday dinners, minus the religious prayers. Instead of attending Hebrew school at a synagogue, Wilks grew up going to a “shule,” or non-religious school that taught him Yiddish.

The pattern continued with his coming-of-age ceremony, which gathered family and friends at a synagogue he never attended.

“It did not involve a Torah reading but instead involved picking any topic related to Judaism that interested me, and then working with a tutor … doing research and basically reading the equivalent of a 13-year-old’s paper” during the ceremony, he said. He chose to explore social justice in Judaism and Jewish history, with a focus on labor movements.

Now a 34-year-old architect living in Philadelphia, Wilks does not believe in god and defines himself explicitly as atheist — but also Jewish. That makes him squarely a “Jew of no religion” according to the survey of U.S. Jews released last week by the Pew Research Center.

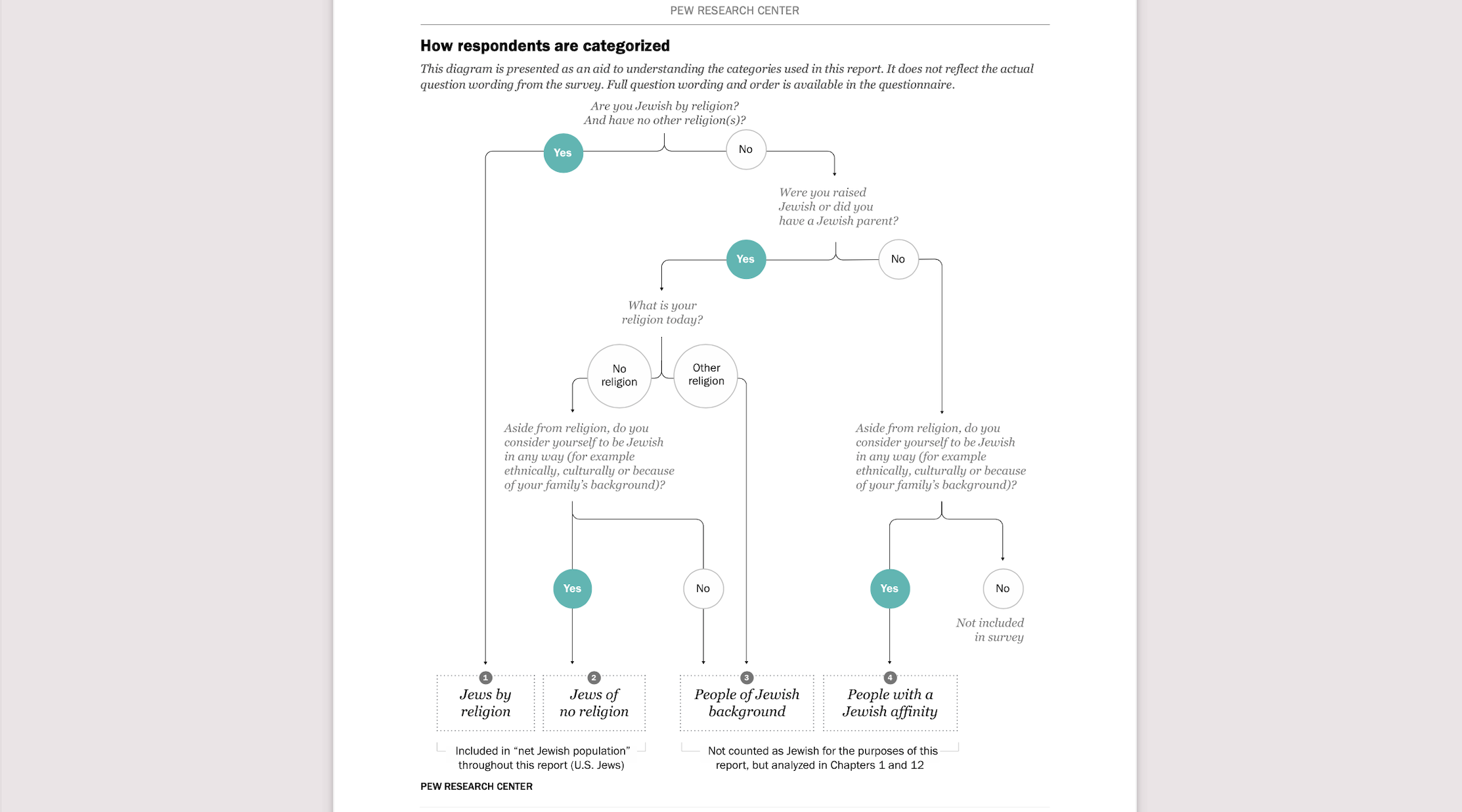

As it did in 2013, Pew researchers broke American Jews into two broad categories: “Jews of religion” and “Jews of no religion.” People in the second group, the researchers wrote, “describe themselves (religiously) as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular, but who have a Jewish parent or were raised Jewish, and who still consider themselves Jewish in any way (such as ethnically, culturally or because of their family background).”

Out of the survey’s 3,836 total respondents, 882 identified as Jews of no religion, suggesting that nearly a quarter of American Jews — 1.5 million people — fall into the category.

Becka Alper, a 2021 study co-author, said the term captures a large and diverse part of the Jewish community that can’t be summarized by other terms such as “cultural Jews” or “ethnic Jews.”

“It really wouldn’t be sufficient to simply ask people about their religion and categorize [only] those who said Jewish as Jews,” she said. “We’d be missing a really big and important part of the Jewish community, those who are Jewish but not namely or at all as a matter of religion.”

This chart from the study shows the researchers’ thought process behind the categories and questions. (Pew Research Center)

Critics of the term say it draws a distinction where there should be none. “The fact that 24% of ‘Jews of no religion’ own a Hebrew-language prayer book should give us pause,” Rachel B. Gross, a professor of Jewish studies at San Francisco State University, wrote in an essay for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency after the study was released.

Gross argues that the study’s categories reflected a division that makes sense to Christians, but not in Judaism, where practice has always shifted over time.

“American Jews continue to find meaning in emotional connections to their families, communities, and histories, though the ways they do so continue to change,” she writes. “Expanding our definition of ‘religion’ can help us better recognize the ways in which they are doing so.”

That argument resonated with three “Jews of no religion” who told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency about their Jewish identities. Here’s what they had to say.

“I feel Jewish every day”

Certain things trigger Wilks’ sense of Jewishness — for instance, watching the Netflix show “Unorthodox,” about a woman leaving her Hasidic community in Brooklyn. While most days Wilks’ knowledge of Jewish customs, rituals and history stays in the “background” of his mind, “Unorthodox” brought it to the “foreground.”

And when he traveled to Berlin during college, he felt his Jewishness turn to visceral vulnerability, in an uncomfortable way.

“I couldn’t walk around and get out of my head that, you know, if I had been there 70 years before, I would have been murdered. And that colored my entire visit there,” he said. “And that was surprising to me that, you know, that my Jewish identity rose and bubbled up there.”

That experience mapped to one finding in the Pew study: 75% of American Jews overall said that “remembering the Holocaust” was important to their Jewish identity, including two thirds of Jews of no religion.

On the other hand, Pew found that while 60% of American Jews say they are strongly or somewhat emotionally attached to Israel, only a third of Jews of no religion described such an attachment. Wilks said he never thinks about the country, where he is entitled to citizenship because of his Jewish lineage.

“I feel zero connection to Israel. To me, it’s the same [as] any country that I haven’t visited,” he said.

Right now, he is still figuring out what kind of Jewish identity he wants in his life as an adult. Growing up, his mother projected a strong sense of non-religious Jewish identity built on her family history, as a descendant of secular Jewish socialist activists from Eastern Europe.

“[I]t’s hard for me to articulate what role [Jewishness] plays in my life,” says Jesse Wilks.

But now living apart from her, and being married to a non-Jewish woman, Wilks feels more disconnected from Jewish culture. (Jews who are married to people who are not Jewish identify three times as often as Jews of no religion, according to Pew.)

Wilks admitted he would be forced to deal with the issue more head on if he had kids, but he and his wife aren’t planning on having any.

“There’s no question I feel Jewish every day and would always identify myself as that. But I don’t know, it’s hard for me to articulate what role that plays in my life,” he said.

Mandy Patinkin, bagels and a preteen existential crisis

In contrast, Sophie Vershbow knows exactly who she is: an atheist cultural Jew.

The 31-year-old social media manager who works for one of the “big five” publishing houses in New York has a deep connection to Jewish culture. She pointed to two things off the top of her head she feels a particular affinity for: actor Mandy Patinkin, and bagels.

Patinkin is an Emmy and Tony winner who became a minor icon this year for weaving Jewish and social justice themes together on social media. People like him in pop culture create a sense of community for other Jews, Vershbow said, and help familiarize non-Jews with Jewish culture.

That’s something the born-and-bred New Yorker said she realized was needed after she left the city for Hamilton College in upstate New York. Jews make up close to 15% of the population of New York City, where she grew up in the Chelsea neighborhood. While Hamilton’s student body was still far more Jewish than the general U.S. population, both the college and the surrounding area felt decidedly non-Jewish to her.

“I called my mom and I was like, ‘What just happened?’ And she goes ‘Sophie, what percent of the country do you think is Jewish?’” Vershbow said. “I studied the Holocaust in college, and learning about our history and how much we’ve been persecuted certainly makes me feel more connected to [my Jewish side]. And makes me feel like it’s important to carry these things on.”

But when it comes to religion, she describes participating in holidays — she still does some of the big ones with her parents, such as Passover and Hanukkah — as “going through the motions,” because she doesn’t believe in god. She grew up attending a Reform synagogue but had an early existential crisis of sorts, just before her bat mitzvah — “a pre-teenage change of heart,” in her words.

“I realized that I didn’t believe in God, and was like, I’m not going to go ahead and do my bar mitzvah. This doesn’t feel right to me,” she said. “Sort of the same way that you figure out you don’t believe in Santa and the Easter Bunny and the Tooth Fairy. It didn’t really work for me.”

Her love of Jewish food (she’s extremely excited to be living near Zabar’s on the Upper West Side these days) is straightforward. Bagels on Sundays, latkes on Hanukkah, kugel around Yom Kippur — that’s something she sees herself instilling in her kids, if she has any in the future.

“I don’t think you have to go to temple for it to be passing [Judaism] down to your kids,” she said. “But if one ever said, you know, ‘Mommy, I want to go check it out, I want to see, I will certainly take my kids to temple and show them.”

Vershbow said she sees no contradiction in her identity — and that being Jewish is at the center of it.

“My family is Polish, Russian, all of that, but … I don’t feel personal connection to any of that. I feel a connection to the American Jewish experience. And that is a huge part of my identity,” she said. “But I think that’s an amazing thing about Judaism is that, for so many people in my own life, it seems to be pretty acceptable in a lot of communities to say: ‘I don’t believe in God, but I am Jewish.’ And these can perfectly coexist within me. And they’re not conflicting.”

Dropping the deity, for decades

With decades of grassroots and congressional politics experience under her belt, 89-year-old June Fischer can rail off an endless list of accomplishments. She has been a delegate from New Jersey in every Democratic National Convention since 1972; she has worked on Joe Biden campaigns since 1974, including his successful presidential run (and became a close friend of his); she worked in the offices of former Sen. Jon Corzine and current Sen. Robert Menendez.

She’s also on the board of her local Jewish community center and in 1990 was a founding member of the National Jewish Democratic Council (now the Jewish Democratic Council of America).

But despite that portion of her resume, she’s not affiliated with a synagogue — showing that the “Jews of no religion” category is not a 21st-century invention.

Fischer grew up in Weequahic, the section of Newark that Philip Roth made famous in his many novels based there. In fact, she graduated from high school with Roth, after sitting next to him in homeroom class for four years.

When she was 15, she went to see Henry Wallace, Franklin Roosevelt’s first vice president, give a speech. She caught the politics bug because of his inspiring performance — not because of any sense of Jewish morality ingrained in her. “I was smitten,” she said.

Although the National Jewish Democratic Council, which she characterized as a liberal response to the AIPAC lobby, and many of the politicians she’s worked with dealt often with Israel-related issues — Biden and Menendez both specialize in foreign policy — Fischer is not a zealous follower of the news in Israel.

And holiday dinners were — and still are for her — more about sticking to tradition than observing religious ritual.

“I do the traditional things, without the deity, as I say,” she said on the phone from her home in Clark. “I’m an atheist, I guess. But I’m fiercely, fiercely traditionally Jewish.”