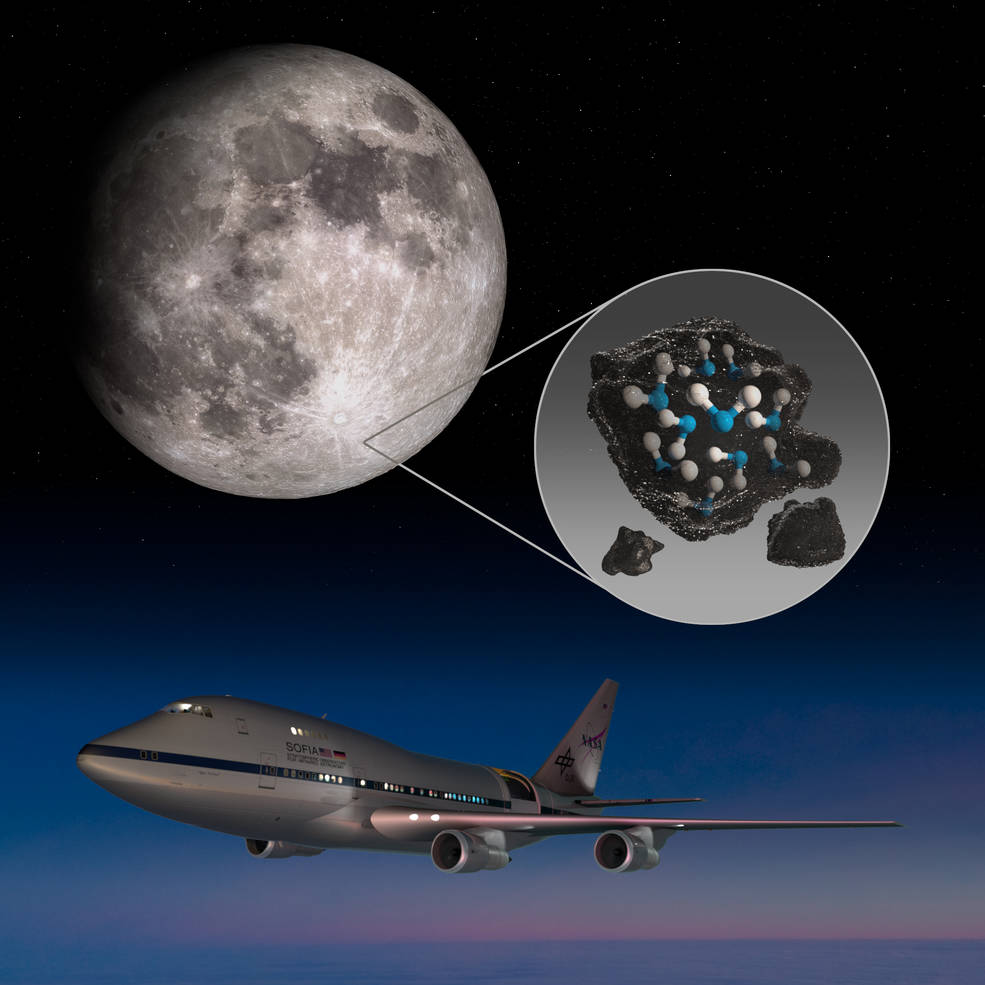

NASA has confirmed, for the first time, water on the sunlit surface of the Moon. This discovery indicates that water may be distributed across the lunar surface, and not limited to cold, shadowed places.

Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) has detected water molecules (H2O) in Clavius Crater, one of the largest craters visible from Earth, located in the Moon’s southern hemisphere.

Although previous observations of the Moon’s surface detected some form of hydrogen but were unable to distinguish between water and its close chemical relative, hydroxyl (OH).

Data from this location reveal water in concentrations of 100 to 412 parts per million – roughly equivalent to a 12-ounce bottle of water – trapped in a cubic meter of soil spread across the lunar surface.

As a comparison, the Sahara desert has 100 times the amount of water than what SOFIA detected in the lunar soil. Despite the small amounts, the discovery raises new questions about how water is created and how it persists on the harsh, airless lunar surface.

Water is a precious resource in deep space and a key ingredient of life as we know it. Whether the water found is easily accessible for use as a resource remains to be determined.

NASA agency is eager to learn all it can about the presence of water on the Moon in advance of sending the first woman and next man to the lunar surface in 2024 and establishing a sustainable human presence there by the end of the decade.

The results are published in the latest issue of Nature Astronomy.

“We had indications that H2O – the familiar water we know – might be present on the sunlit side of the Moon,” said Paul Hertz, director of the Astrophysics Division in the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Now we know it is there. This discovery challenges our understanding of the lunar surface and raises intriguing questions about resources relevant for deep space exploration.”

When the Apollo astronauts first returned from the Moon in 1969, it was thought to be completely dry. Orbital and impactor missions over the past 20 years, confirmed ice in permanently shadowed craters around the Moon’s poles.

Meanwhile, several spacecraft looked broadly across the lunar surface and found evidence of hydration in sunnier regions. Yet those missions were unable to definitively distinguish the form in which it was present – either H2O or OH.

“Prior to the SOFIA observations, we knew there was some kind of hydration,” said Casey Honniball, the lead author who published the results from her graduate thesis work at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa in Honolulu. “But we didn’t know how much, if any, was actually water molecules – like we drink every day – or something more like drain cleaner.”