Little green men and lorries after the seizure of Perevalne military base, 9 March 2014 credit Anton Holoborodko

by Tatsiana Kulakevich, University of South Florida

U.S. President Joe Biden said on Jan. 19, 2022, that he thinks Russia will invade Ukraine, and cautioned Russian president Vladimir Putin that he “will regret having done it,” following months of building tension.

Russia has amassed an estimated 100,000 troops along its border with Ukraine over the past several months.

In mid-January, Russia began moving troops into Belarus, a country bordering both Russia and Ukraine, in preparation for joint military exercises in February.

Putin has issued various security demands to the U.S. before he draws his military forces back. Putin’s list includes a ban on Ukraine from entering NATO, and agreement that NATO will remove troops and weapons across much of Eastern Europe.

There’s precedent for taking the threat seriously: Putin already annexed the Crimea portion of Ukraine in 2014.

Ukraine’s layered history offers a window into the complex nation it is today — and why it is continuously under threat. As an Eastern Europe expert, I highlight five key points to keep in mind.

Adam Schultz/The White House

What should we know about Ukrainians’ relationship with Russia?

Ukraine gained independence 30 years ago, after the fall of the Soviet Union. It has since struggled to combat corruption and bridge deep internal divisions.

Ukraine’s western region generally supported integration with Western Europe. The country’s eastern side, meanwhile, favored closer ties with Russia.

Tensions between Russia and Ukraine peaked in February 2014, when violent protesters ousted Ukraine’s pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych, in what is now known as the Revolution of Dignity.

Around the same time, Russia forcibly annexed Crimea. Ukraine was in a vulnerable position for self-defense, with a temporary government and unprepared military.

Putin immediately moved to strike in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. The armed conflict between Ukrainian government forces and Russia-backed separatists has killed over 14,000 people.

Unlike its response to Crimea, Russia continues to officially deny its involvement in the Donbas conflict.

What do Ukrainians want?

Russia’s military aggression in Donbas and the annexation of Crimea have galvanized public support for Ukraine’s Western leanings.

Ukraine’s government has said it will apply for European Union membership in 2024, and also has ambitions to join NATO.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who came to power in 2019, campaigned on a platform of anti-corruption, economic renewal and peace in the Donbas region.

In September 2021, 81% of Ukrainians said they have a negative attitude about Putin, according to the Ukrainian news site RBC-Ukraine. Just 15% of surveyed Ukrainians reported a positive attitude towards the Russian leader.

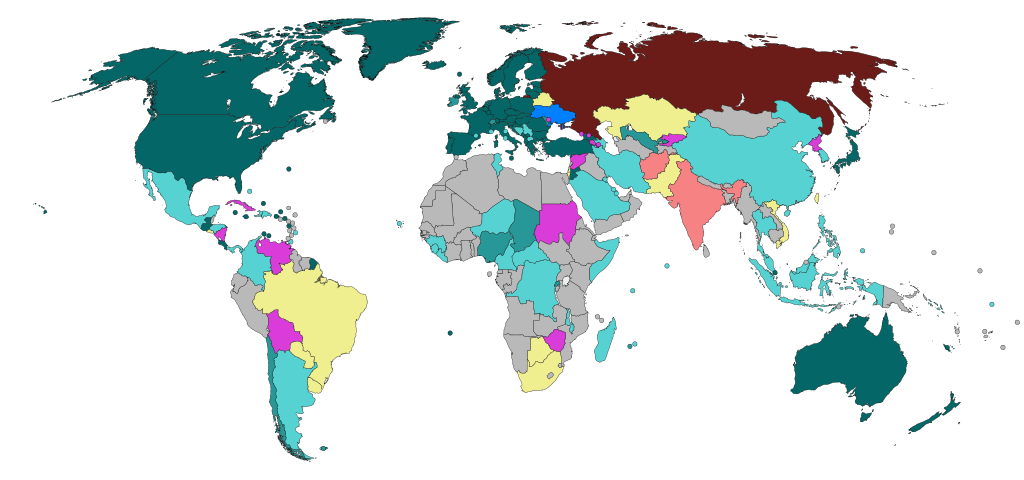

International reaction to the 2014 Crimean crisis – (Yellow) Statements only voicing concern or hope for peaceful resolution to the conflict (Turquoise) Support for Ukrainian territorial integrity (Light green) Condemnation of Russian actions (Dark Green) Condemnation of Russian actions as a military intervention or invasion (Purple) Support for Russian actions and/or condemnation of the Ukrainian interim government (Pink) Recognition of Russian and other interests of the conflict” (Blue) Ukraine (Brown) Russia

Why is Putin threatening to invade Ukraine?

Putin’s decision to engage in a military buildup along Ukraine is connected to a sense of impunity. Putin also has experience dealing with Western politicians who champion Russian interests and become engaged with Russian companies once they leave office.

Western countries have imposed mostly symbolic sanctions against Russia over interference in the 2020 U.S. presidential elections and a huge cyberattack against about 18,000 people who work for companies and the U.S. government, among other transgressions.

Without repercussions, Putin has backed Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko’s brutal crackdown on mass protests in the capital city, Minsk.

In several instances, Putin has seen that some leading Western politicians align with Russia. These alliances can prevent Western countries from forging a unified front to Putin.

Former German chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, for example, advocated for strategic cooperation between Europe and Russia while he was in office. He later joined Russian oil company Rosneft as chairman in 2017.

Other senior European politicians promoting a soft position toward Russia while in office include former French Prime Minister François Fillon and former Austrian foreign minister Karin Kneissl. Both joined the boards of Russian state-owned companies after leaving office.

What is Putin’s end game?

Putin views Ukraine as part of Russia’s “sphere of influence” – a territory, rather than an independent state. This sense of ownership has driven the Kremlin to try to block Ukraine from joining the EU and NATO.

In January 2021, Russia experienced one of its largest anti-government demonstrations in years. Tens of thousands of Russians protested in support of political opposition leader Alexei Navalny, following his detention in Russia. Navalny had recently returned from Germany, where he was treated for being poisoned by the Russian government.

Putin is also using Ukraine as leverage for Western powers lifting their sanctions. Currently, the U.S. has various political and financial sanctions in place against Russia, as well as potential allies and business partners to Russia.

A Russian attack on Ukraine could prompt more diplomatic conversations that could lead to concessions on these sanctions.

The costs to Russia of attacking Ukraine would significantly outweigh the benefits.

While a full scale invasion of , Putin might renew fighting between the Ukrainian army and Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine.

Why would the US want to get involved in this conflict?

With its annexation of Crimea and support for the Donbas conflict, Russia has violated the Budapest Memorandum Security Assurances for Ukraine, a 1994 agreement between the U.S., United Kingdom and Russia that aims to protect Ukraine’s sovereignty in exchange for its commitment to give up its nuclear arsenal.

Putin’s threats against Ukraine occur as he is moving Russian forces into Belarus, which also raises questions about the Kremlin’s plans for invading other neighboring countries.

Military support for Ukraine and political and economic sanctions are ways the U.S. can make clear to Moscow that there will be consequences for its encroachment on an independent country. The risk, otherwise, is that the Kremlin might undertake other military and political actions that would further threaten European security and stability.![]()

Tatsiana Kulakevich, Assistant Professor of instruction at School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies, affiliate professor at the Institute on Russia, University of South Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.