On the holiday of Shavuot, the biblical book of Ruth is read in synagogue. Explanations for this practice include the springtime setting of both the tale and the holiday, as well as the heroine’s acceptance of Judaism, which thematically connects to the festival’s commemoration of the acceptance of God’s law at Sinai by the Israelites in the days of Moses. While the scriptural story records Ruth as the ancestor of King David, American history credits her as a figure who helped advance civil rights and liberty.

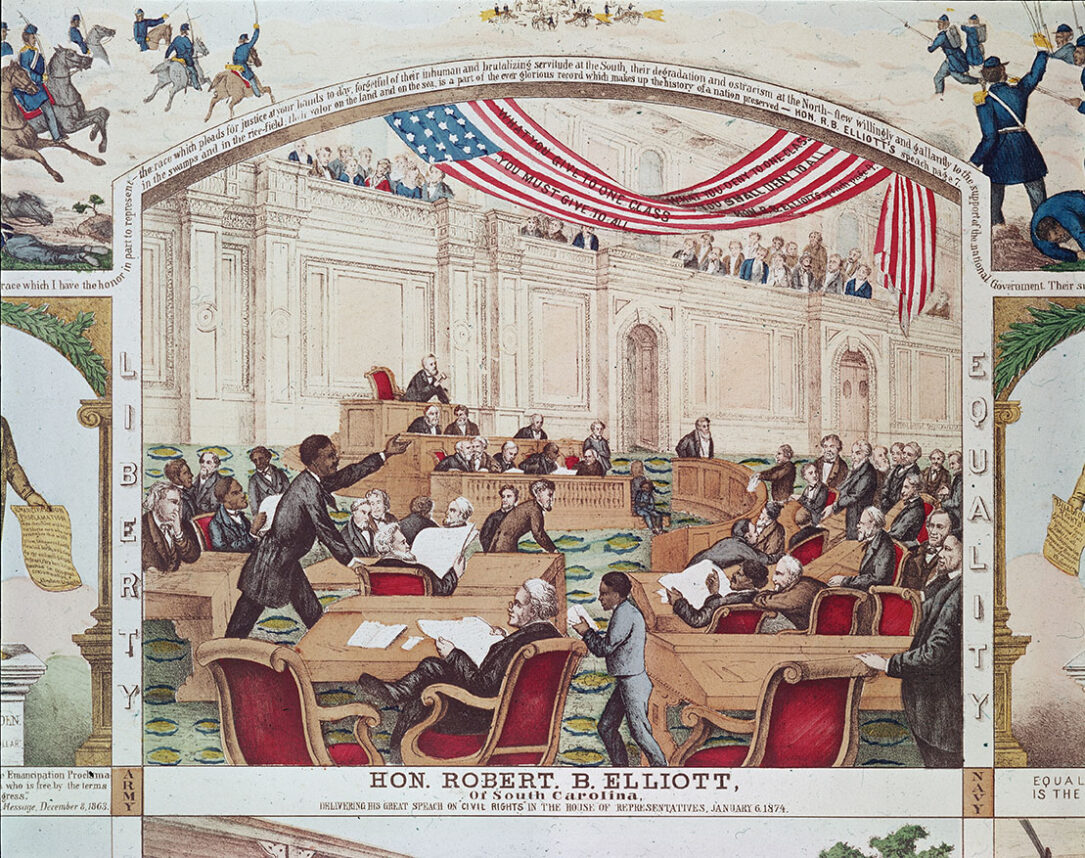

In a Jan. 6, 1874 speech, Representative Robert Brown Elliott invoked the heroine in arguing before Congress on behalf of equal treatment for all Americans.

Elliott was a fascinating figure. Born in 1842 in Liverpool, England, he was educated at the prestigious Eton College, served in the British Royal Navy, and then immigrated to America, where he settled in South Carolina in 1867. There he campaigned against the Ku Klux Klan, was elected to the state legislature and later commanded the South Carolina National Guard, the first Black man to do so. Elliott also served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1870 to 1874. It was there that he gave a speech urging the passage of what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Powerfully, he began by arguing that while the cause was undoubtedly personally relevant, that was not why he was advocating for the legislation: “While I am sincerely grateful for this high mark of courtesy that has been accorded to me by this House,” he said, “it is a matter of regret to me that it is necessary at this day that I should rise in the presence of an American Congress to advocate a bill which simply asserts equal rights and equal public privileges for all classes of American citizens. I regret, sir, that the dark hue of my skin may lend a color to the imputation that I am controlled by motives personal to myself in my advocacy of this great measure of national justice. Sir, the motive that impels me is restricted by no such narrow boundary but is as broad as your Constitution. I advocate it, sir, because it is right.”

Citing Alexander Hamilton’s argument that “natural liberty is a gift of the beneficent Creator to the whole human race,” Elliott reminded the House that “it is scarcely 12 years since [the South] shocked the civilized world by announcing the birth of a government which rested on human slavery as its cornerstone.” He expressed relief that the “progress of events has swept away that pseudo-government which rested on greed, pride, and tyranny.”

The bill on the floor, Elliott believed, “does not seek to confer new rights, nor to place rights conferred by state citizenship under the protection of the United States, but simply to prevent and forbid inequality and discrimination on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” If it was to pass, the congressman passionately proclaimed, “it will form the capstone of that temple of liberty, begun on this continent under discouraging circumstances, carried on in spite of the sneers of monarchists and the cavils of pretended friends of freedom, until at last it stands in all its beautiful symmetry and proportions, a building the grandest which the world has ever seen, realizing the most sanguine expectations and the highest hopes of those who, in the name of equal, impartial, and universal liberty, laid the foundation stones.”

It was then that he turned to the ancient Jewish figure of Ruth.

“The Holy Scriptures,” Elliott concluded, “tell us of a humble handmaiden who long, faithfully, and patiently gleaned in the rich fields of her wealthy kinsman; and we are told further that at last, in spite of her humble antecedents, she found complete favor in his sight.”

To this British-born, black American Congressman, Ruth’s having earned full acceptance into the nation of Israel foreshadowed the expansion of equality in the American national narrative. Should the law be enacted, should all citizens receive the equal rights they deserve, “we may, with hearts overflowing with gratitude, and thankful that our prayer has been granted, repeat the prayer of Ruth: ‘Entreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee; for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge; thy people shall be my people, and thy god my God; where thou diest, will I die, and there will I be buried; the Lord do so to me, and more also, if aught but death part thee and me.”

Quoting Ruth’s pledge of loyalty to her mother-in-law Naomi as the two headed to the Promised Land, Elliott saw a prefiguring of the march of American liberty.

Even after Elliott’s well-received speech, and the Civil Rights Act’s passage, the path towards full equality for all Americans would remain long and winding. But Ruth would remain as an inspiration for advocates of social equality and freedom in our country.

Helen Keller, born in Tuscumbia, Alabama six years after Elliott’s speech, also reflected on the biblical figure’s foundational impact on her advocacy for equality. After losing her sight and hearing after an illness at 19 months old, Keller, under the tutelage of her teacher Anne Sullivan, learned to read and write. Her graduation at Harvard made her the first deafblind person to earn an undergraduate degree in U.S. history. She campaigned on behalf of disability rights, women’s suffrage and labor rights, and co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). In her 1903 autobiography, “The Story of My Life,” Keller wrote movingly of her love of the Bible.

“[H]ow shall I speak of the glories I have since discovered in the Bible?” she wrote. “For years I have read it with an ever-broadening sense of joy and inspiration; and I love it as I love no other book.” She expressed an affinity for Esther, the ancient Persian Jewish queen, wondering, “[c]ould there be anything more dramatic than the scene in which Esther stands before her wicked lord? She knows her life is in his hands; there is no one to protect her from his wrath. Yet, conquering her woman’s fear, she approaches him, animated by the noblest patriotism, having but one thought: ‘If I perish, I perish; but if I live, my people shall live.’”

But Keller’s favorite figure was Ruth. “Ruth is so loyal and gentle-hearted,” she enthused. “We cannot help loving her, as she stands with the reapers amid the waving corn. Her beautiful, unselfish spirit shines out like a bright star in the night of a dark and cruel age. Love like Ruth’s, love which can rise above conflicting creeds and deep-seated racial prejudices, is hard to find in all the world.”

Decades later, as the United States faced the greatest threat to liberty that the world has ever known, the Nazi menace, Ruth reappeared once more.

Decades later, as the United States faced the greatest threat to liberty that the world has ever known, the Nazi menace, Ruth reappeared once more. Harry Hopkins, a trusted deputy of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, attended a dinner in England in January 1941, to show support for Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The setting was dire. As Hopkins’ granddaughter, historian June Hopkins, has recounted, “Hitler’s armies now held most of Western Europe, and seemed to be rolling through the Soviet Union; Congress was squabbling over intervention versus isolation; Britain and the Commonwealth seemed to be losing everywhere.”

Though America would not enter WWII for a few more months, Hopkins was there to express American support for the Allies. As his granddaughter would later write, “though [Harry Hopkins] had no official title, some called him (not always with approval) the ‘Assistant President.’ He certainly wielded extraordinary influence in the White House. But Hopkins was not a shadowy figure hovering in the background, nor was he merely an intermediary. He served, rather, as a kind of third leg of a tripod. Churchill and Roosevelt had previously viewed each other with a wary eye; Hopkins provided stability for the often-tenuous balance between two powerful leaders with very different world outlooks.”

During the dinner, Hopkins turned to the Prime Minister and said: “I suppose you wish to know what I am going to say to President Roosevelt on my return. Well, I’m going to quote you one verse from that Book of Books. . . . ‘Whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.’” And, added Hopkins, “even to the end.”

Throughout the American story, Ruth has reverberated, reminding us, then and now — as we read her eponymous book once more on the holiday of Shavuot — of the power of one individual’s faith and loyalty to inspire the fight for freedom and liberty.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”