TEL AVIV — Two former Soviet republics that have been sworn enemies ever since the breakup of the USSR are suddenly on the verge of making peace.

Since even before their independence in 1991, predominantly Christian, landlocked Armenia and mostly Muslim, oil-rich Azerbaijan have fought many wars over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region and accused each other of human rights abuses, ethnic cleansing — even genocide.

But now, their leaders say they have decided to bury the hatchet — and Jews in both countries could benefit.

On Aug. 8, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev met at the White House with President Donald Trump. Together, the three men signed documents aimed at ending the hostilities that had defined Armenian-Azerbaijani relations for more than 35 years.

“We are very happy about this agreement,” said Shneor Segal, chief rabbi of the Ashkenazi community of Azerbaijan and head of the Chabad movement there. “As Jews, we always pray for peace. Friendship between neighbors can only bring good things, so any move toward peace and co-existence is positive.”

Alexandra Livergant, a Russian Jew who’s been living in Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, since early 2022, said the Armenians treat her kindly — but that attitudes toward individual Jews they meet and towards Israel as a state are two distinct things.

“Overall, the situation may improve, because a peace agreement means there will be no war — which also means that Israel will stop selling weapons to Azerbaijan,” said Livergant, a journalist who hosts public talks, interviews and podcasts. “This could ease a major source of tension.”

Armenian girls study Jewish religious texts under the direction of Rabbi Gershon Meir Burshtein in Yerevan. (Larry Luxner)

Azerbaijan has roughly three times the land area and population as Armenia, with roughly 10.2 million people inhabiting a country the size of Maine. Home to indigenous Jews since shortly after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, in 586 BCE, Azerbaijan also boasts the world’s first oil well. By the 1920s, it was producing more than half the planet’s petroleum.

Today, this republic bordering the Caspian Sea still relies on energy exports for most of its revenues — helping to turn its capital city, Baku, into a mini-Dubai. About 96% of its inhabitants are Muslims, with no restrictions placed on the practice of other faiths.

That has allowed the tiny fraction of Azerbaijanis who identify as Jews to thrive — a rarity in the Islamic world.

“Azerbaijan’s Jewish community wrote a letter to our president congratulating him for this agreement. And of course, we would love to have peace with Armenia. But here in Azerbaijan, we are already living in peace and harmony,” said Rabbi Zamir Isayev, chairman of the Sephardic Community of Baku. He said Azerbaijan represented the rare “Muslim country where Israeli tourists can speak Hebrew, relax and feel at home.”

Estimates of how many Jews live in Azerbaijan vary wildly. Shneor and Isayev put the number at 25,000 or even 30,000 — with roughly 65% of that total being so-called “Mountain Jews” of Persian origin (whose ranks include a member of the country’s Eurovision act this year), another 25% Ashkenazi Jews fleeing Europe who began arriving in 1811, and the remaining 5% Jews from neighboring Georgia.

But the World Jewish Congress puts the number at 7,200, and Itsik Moshe, a former Jewish Agency official who runs the Israel-Georgia Chamber of Business from Tbilisi, doubts that more than 10,000 Jews reside in all three countries combined — maybe 8,000 in Azerbaijan and 1,000 each in Georgia and Armenia. At the same time, he said, Israel is now home to 200,000 immigrants from the three South Caucasus nations.

A prayer service in the Six-Domed Synagogue in Qrmz Qsb, or Red Town, in the Quba district of Azerbaijan, Sept. 28, 2016. (Oleksandr Rupeta/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Armenia, roughly the size of Maryland, has a population of 3 million. In 301 CE, it became the world’s first country to adopt Christianity, and its unique 39-letter alphabet dates to the year 405 CE. About 97% of Armenia’s inhabitants follow the Armenian Apostolic Church, with Catholics, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews and others making up the remaining 3%.

Proof of Armenia’s ancient Jewish heritage is a cemetery in the remote village of Yeghegis — about two hours’ drive east of Yerevan. Here, past a metal gate decorated with a Star of David, lie 64 complete tombstones and fragments of others dating from 1266 to 1346, with inscriptions written in Hebrew and Aramaic.

Isayev said that once real peace comes to the region, “we hope Armenia will learn from Azerbaijan how to respect minorities and protect its Jews.”

That’s a reference to the repeated vandalism in recent years of Armenia’s only synagogue, the Mordechay Navi Jewish Religious Center in Yerevan. In September 2023, then again on Oct. 3 — four days before the Hamas assault on Israel — and again in November of that year, unknown assailants attacked the shul, according to its spiritual leader, Rabbi Gershon Burshtein.

Entrance to the ancient Jewish cemetery in Yeghegis, Armenia, which contains nearly 40 medieval tombstones from the 13th and 14th centuries C.E. inscribed in Hebrew and Aramaic. (Larry Luxner)

In each case, damage was minimal, though the third time, masked men set the building on fire and later claimed to be acting on behalf of a shadowy Armenian “liberation army” that opposes Israel’s ties to Azerbaijan. Burshtein told JR at the time that he believed the attacks were perpetrated not by locals, but by people acting on behalf of Azerbaijan or Russia in a blatant false-flag attempt “to portray Armenia as a country where antisemitism dominates.”

Antisemitism is, in fact, a recurring problem in Armenia.

Much of it stems from the billions of dollars’ worth of Israeli heavy artillery, rocket launchers and drones that helped Azerbaijan defeat Armenia in a 44-day war in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War of 2020. That victory allowed Azerbaijan to reclaim Nagorno-Karabakh and, in September 2023, expel virtually the entire population of 120,000 ethnic Armenians who had been living there.

Armenia subsequently accused Azerbaijan of ethnic cleansing, though the Azerbaijanis point to the earlier Khojaly massacre of Feb. 26, 1992, in which Armenian forces were said to have killed at least 200 Azerbaijani civilians — and possibly as many as 1,000 — depending on the source. Genocide museums in both Yerevan and the Azerbaijani city of Quba attest to the horrific crimes attributed to each countries’ respective enemies.

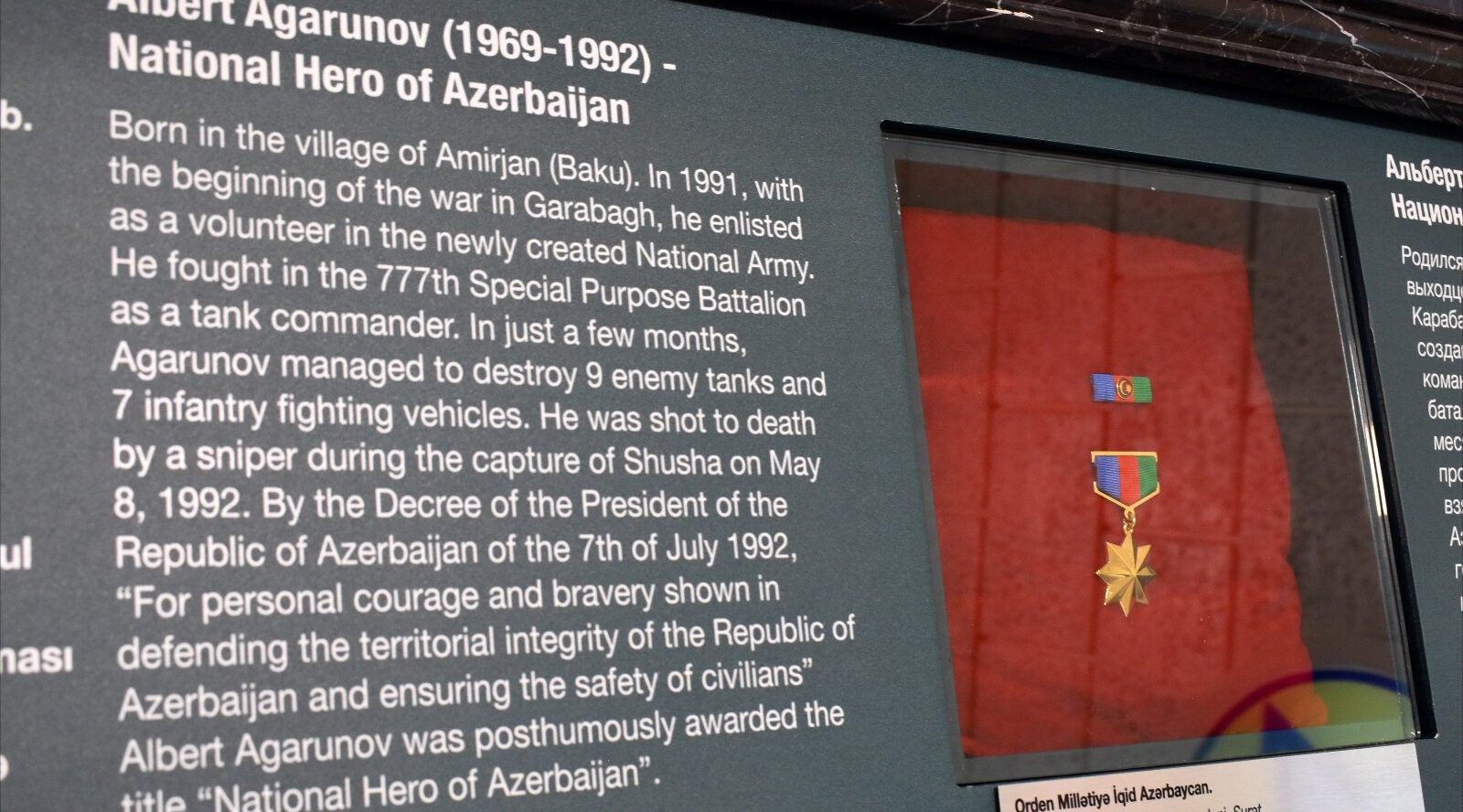

Notably, an entire exhibit at Azerbaijan’s Museum of Mountain Jews in Krasnaiya Sloboda is devoted to Albert Agarunov, a 23-year-old Jewish tank commander who was posthumously awarded the title National Hero of Azerbaijan after an Armenian sniper shot him to death. That 1992 conflict displaced up to a million people, including Jews who had been living in the disputed Karabakh region.

An exhibit at Azerbaijan’s Museum of Mountain Jews in Krasnaiya Sloboda is devoted to Albert Argarunov, a Jewish soldier who was killed in fighting in 1992. (Larry Luxner)

Armenians are also unhappy that Israel hasn’t officially recognize the 1915-23 genocide of 1.5 million Armenians at the hands of the Ottoman Turks — a step 34 other nations including the United States has taken.

Under the deal initialed Aug. 8 by Azerbaijan’s Aliyev and Armenia’s Pashinyan, as well as Trump — who’s made no secret of his desire to win a Nobel Peace Prize — both countries agree to end their hostilities and renounce all legal claims against each other.

Central to the deal is the 27-mile Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity, known as TRIPP, formerly known as the Zangezur Corridor. It aims to connect Azerbaijan with its exclave, Nackchivan — separated by a swath of Armenian territory — and is to be developed by U.S. companies to include rail and communication lines as well as oil and gas pipelines. It also seeks to prevent Russia from monopolizing the conflict, which is something neither side wants.

“Now they’re friends, and they’re going to be friends for a long time,” Trump told reporters at the White House signing ceremony. “You two are going to have a great relationship. If you don’t, call me and I’ll straighten it out.”

Nathaniel Trubkin, coordinator of the Yerevan Jewish Home community, hopes the possibility of peace between the two Caucasus countries will also improve Armenia’s ties with Israel.

“In Yerevan, many people see Israel more as a supporter of their enemy than as a partner. But this peace accord could change the atmosphere,” said Trubkin, who’s originally from Moscow. “Armenia now has a chance to build productive relations with Israel outside the context of war.”

The vast majority of Armenia’s 1,000 or so Jews are, like Trubkin, recent arrivals from Russia and Ukraine who fled both countries after war between them broke out in February 2022. Many of them hold Israeli passports, he said.

“From my perspective, Armenia has many educated, modern people who would like to build productive relations with Israel,” he said. “But for this to happen, there must also be initiative from Israelis, and our Russian Jewish community in Yerevan can play an important role in this.”

Indeed, contact between Armenian and Azerbaijani Jews is nonexistent, largely because for years it’s been virtually impossible for Armenian citizens to visit Azerbaijan and vice-versa. That lack of communication extends to the rabbis themselves.

“Most Azerbaijani Jews didn’t even know there were Jews in Armenia. They learned it only after they saw on the news that a synagogue in Yerevan was attacked,” said Isayev, who’s served as a rabbi for 18 of his 44 years.

Added Segal, 46, who arrived in Baku from Israel in 2010: “My duty is to work with the Jews of Azerbaijan. Until now, there was no need to reach out because you couldn’t travel to Armenia. But if things open up, everything could happen.”

In contrast to Armenia, neighboring Azerbaijan currently has seven active synagogues — three in Baku, three in Quba and two in Oğuz, a city near the Georgian border. Chabad also has seven emissaries throughout the country, as well as the Or Avner Educational Complex, which currently has 203 students from ages 3 to 18.

A panoramic view of Krasnaiya Sloboda, an all-Jewish shtetl near Quba, Azerbaijan. (Larry Luxner)

In addition, Chabad operates Baku’s only kosher restaurant, Rimon, for the past three years, as more Israelis start streaming into the country.

Jamilya Talibzadeh, director of the Azerbaijan Tourism Office in Israel, said AZAL currently offers 14 flights a week between Tel Aviv and Baku. Arkia will start flying that route in October with three flights per week.

During the first seven months of 2025, she said, about 30,000 Israelis visited Azerbaijan — nearly double the number who visited in 2024.

In early November, Azerbaijan will host the 70th anniversary convention of the Conference of European Rabbis. Expected to attract 500 Orthodox rabbis, the Nov. 4-6 gathering will mark the first time the group has convened in a Muslim nation. High on the agenda: expansion of the Abraham Accords to include Azerbaijan and possibly other predominantly Muslim nations in Central Asia.

“I think peace in this region will not only be good for Jews in both Armenia and Azerbaijan, but also for Georgia and the whole region,” said Moshe. “Stability will bring more trade among Israel and Azerbaijan, but also between Israel and Armenia. But personally, I think the only solution for Jews is to make aliyah. Then they can come back here to work if they want — but as Israelis.”

Keep Jewish Stories in Focus.

JR has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.