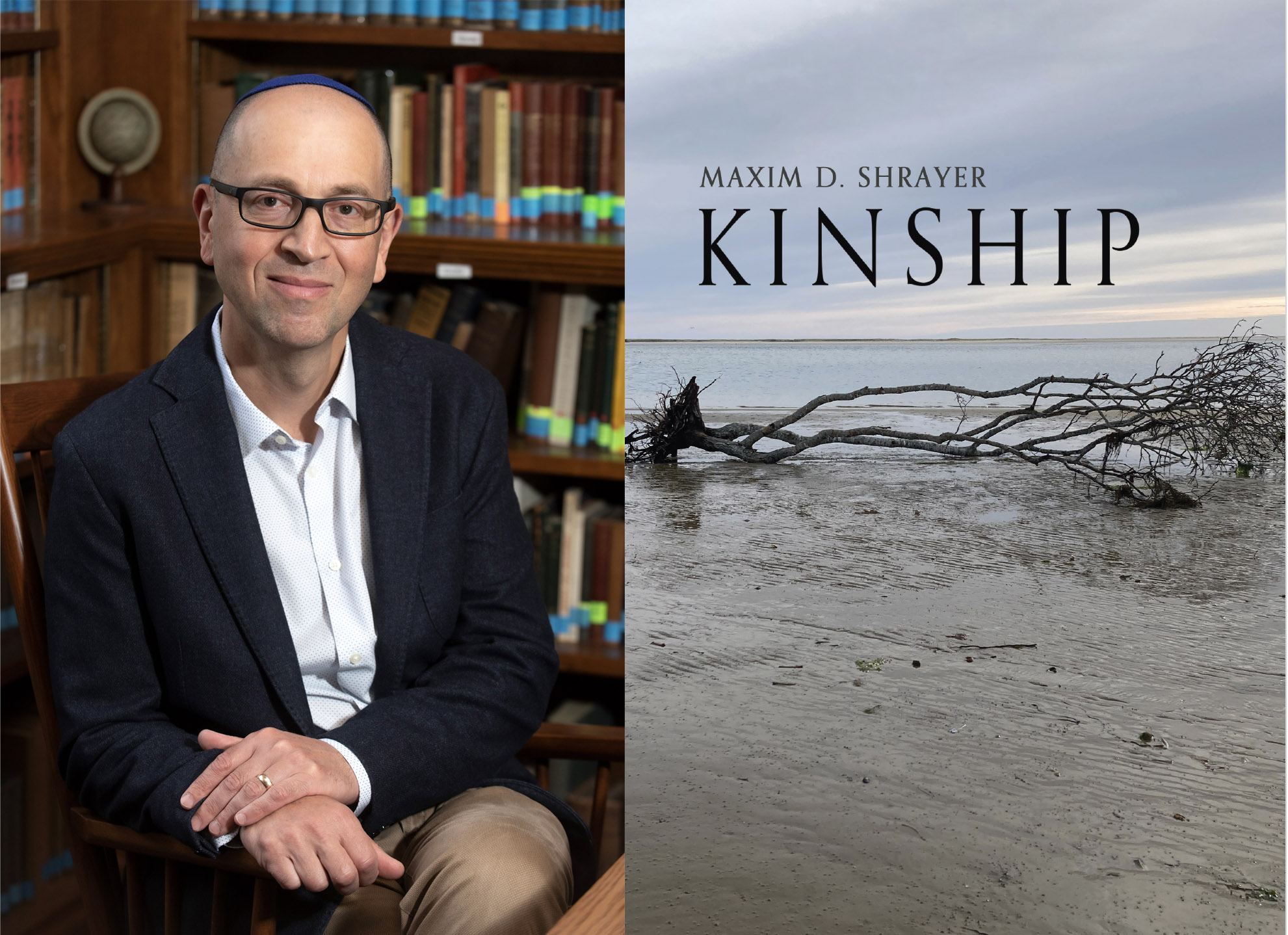

Maxim D. Shrayer frequently travels between the inner worlds that constitute his identity. In his latest collection of poems, “Kinship,” Shrayer offers many a glimpse into what it’s like to be living within each of his worlds. There is the scholarly side of him, as a professor of Russian, English and Jewish Studies at Boston College, where he does not shy away from tough questions. There is the literary side of him as an author: a poet committed to speaking out against antisemitism and Israel-hate, and decrying the violence Russia, the country of his birth, commits against his ancestral land, Ukraine. Shrayer was raised in a literary family in Moscow, and intimate connections to the art of poetry flow through his veins. Then there is the part of him as a translator using poetry to keep him connected to his Jewish and East European roots, writing in Russian and English—while the Russia-Ukraine war threatens to erase vestiges of his past.

Shrayer grew up as a refusenik—a Soviet Jew denied emigration—and eventually entered the United States as a political refugee in 1987. He has authored and edited thirty books in English and Russian, among them the internationally acclaimed memoirs “Leaving Russia: A Jewish Story” and “Waiting for America: A Story of Emigration,” the collection of novellas “A Russian Immigrant,” and, more recently, the literary memoir “Immigrant Baggage.” Shrayer is the recipient of a National Jewish Book Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship. His works have been translated into thirteen languages.

Shrayer’s new collection, “Kinship” (Finishing Line Press), is a deeply personal body of work dedicated to sharing his experiences of his ethnic, religious, and cultural identities as a Jew, an ex-Soviet, and an immigrant to America in a time when all parts of his identity are pulled in different directions.

Shrayer generously agreed to discuss “Kinship”—its making and what his hopes are for the book.

Eva Levy: As I read the poem “Tired,” I felt how clearly you spoke of emotional exhaustion through the lines “A Jew is tired of being weird / A Jew is tired of feeling admired.” Of the many feelings throughout “Kinship” that come with the Jewish identity, how did you decide on placing “weird” and “admired” together?

Maxim D. Shrayer: “In poetry, a lot is decided by the magical confrontation of sounds. Choices that poets make are in some instances deliberate, but in others come out of hearing a certain meaningful connection—simply because words share a pattern. The poem ‘Tired’ came from what I feel almost all the time: that pretty much every person has an opinion about being Jewish. The initial emotional impulse behind the poem came from feeling tired of constantly being configured by everybody else, without necessarily taking the time to understand what a Jewish person actually represents as a human being. Then the poem took me in various directions, both positive and negative, both secular and religious. It eventually brings you to the question of waiting for the Messiah … I guess the coupling of ‘weird’ and ‘admired’ in my poem suggests that interpreting Jews is some sort of a morbid universal obsession, which comes, on the one hand, from prejudice, but, on the other hand, from a strange admiration, and the prejudice feeds on the admiration and the admiration on prejudice. It’s probably not a very healthy dynamic.”

EL: I believe “Tired” is also the one you shaped in an exclamation point.

MDS: “Yes, I’m glad you picked that up, but also the dot at the very bottom is shaped as a Star of David. So it’s an exclamation that has a particular configuration. And I don’t know what poem I would write if I were writing this poem after the Hamas attack on Israel, because I think being Jewish is not just feeling tired; it’s mortally exhausting.”

“I wanted the poem to feel almost like a funeral procession with a heavy, thunderous step.”

“In some cases, I choose the particular form because I find it especially advantageous, but in other cases, I think it’s just an organic process; verse comes to me in a certain shape, and then I perfect it. There’s a lot of discipline in working with form … and I think that certain subject matters in poetry demand a particular intentionality of form and structure. The title poem, for instance, is really about the fighting in Ukraine. I wanted the poem to feel almost like a funeral procession with a heavy, thunderous step.”

EL: The first and last poems of the collection, “Kinship” and “Homecoming,” are similarly styled in their texture and line length.

MDS: “That’s intentional, and there is a certain historical logic to it. There’s also a logic that has to do with how this book records my changed relationship, on the one hand, with my roots in the former Soviet Union, and on the other hand, with Russian, my first language, still one of the two languages in which I write. When Russia invaded Ukraine, I remember, I woke up feeling that it was the end of my previous relationship with Russia, and also with Russian language and culture. The title poem, ‘Kinship,’ is in many ways about that. It’s about this new demarcation line. For as long as Putin is in power, I could never go back. At the same time … imagine, if I never get to go to Russia again, for how long will I be sustained by just what I have with me, in me? Will there be a point when I will feel like I’m out of oxygen of Russian culture? The collection’s final long poem envisions an émigré artist who left many, many decades ago and still thinks about return. And he returns because he realizes that the only way he can punish Putin’s regime is by miraculously taking all his words out of his books in Russia’s libraries.”

EL: Who is the prototype of the exiled writer in your poem?

MDS: “The prototype of the person whom I call ‘the Composer’ is the great Russian-American writer Vladimir Nabokov, the author of ‘Lolita.’ Nabokov left Russia when he was 19 and spent his literary career abroad, first in interwar Europe and then in America and Switzerland. And he never went back to the Soviet Union. In the book I call him the Composer because in the highest sense, all writing is composition. But also, I was thinking that this émigré cannot go back to the place that used to be his home, and so he imagines all his words as his troops. And like a general, he commands them to follow him, and they follow him out of Russia. Nabokov always insisted that there was no going back as long as the Bolsheviks were in power. And I also feel this way, very strongly, about Putin’s regime.”

“You are right that these two poems, the longer, expansive poems, are like the two bookends. The first one is about my personal story, while the second one is more of a collective story of exile. Both have to do with the impossibility of return … for as long as a dictatorial regime, a bloody regime, rules Russia. Many dictatorships likes to present themselves to the world as a place where culture is valued, as a place of high culture. So if, by some miracle, all writers would extract all their works from the Russian libraries, Putin’s regime would be left with empty pages.”

EL: In the poem “Batya Kahana’s Disappearance,” you write of your ancestor whose lost Russian-language compositions intrigue you. You paint a vivid image of where you see the box of originals hiding. What does it mean to you that one part of your culture is lost in the city of another, yet preserved in writing, as you’ve made a book connecting them all?

MDS: “It’s an interesting story that, unfortunately, will most likely never be accorded a resolution. It’s about one of my father’s aunts, on the paternal side, on the Shrayer side. Back then our large Jewish family was living in what is now Ukraine, at the time part of the Russian Empire, in the area close to the former border with the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Several children, as young people, went to what in the early 1920s was the British Mandate of Palestine. There was no Israel, there was no Jewish statehood, just hopes. They were young Socialist-Zionists. The future Batya Kahana—it was not her birth name, it became her literary name—was writing fiction in Russian. She arrived in Mandatory Palestine. Tel Aviv was just being built from scratch. And so she arrived, some family members were already there, while another part of the family stayed behind in the Soviet Union. Batya’s husband did quite well and quickly became upper middle class. The house that I refer to in the poem, it still exists and it’s in a beautiful part of Tel Aviv, which was built in the style of Bauhaus architecture. Batya’s husband was a very nice man. He understood that she had a gift and he said to her, ‘Look, we’re here, the language of the future is Hebrew, there’s no point in publishing in Russian. So why don’t we hire good translators, who would translate your work from Russian into Hebrew, and we will publish it in Hebrew?’

“From the middle 1920s she started publishing novels and collections of stories in Hebrew, and published a number of them and achieved some acclaim … It’s a long story. In the 1950s Batya Kahana disappeared from literary life, and if you talk to students of Hebrew literature today, they will say ‘yeah of course, she’s an early forgotten Hebrew writer.’ Except her work was originally in Russian. And so, my great interest, once I put all these things together from talking to older family members in Israel, has been to figure out what happened. Originally we thought that Batya’s manuscripts were given to an archive. And I had Israeli archivists search; some of her letters are in archives, but not her manuscripts. For a period of time, the family thought that some boxes were left in this house where they lived, I believe until the 1960s. I kept thinking, next time I go to Israel, I’m going to put Batya’s daughter, who is now in her eighties, in a cab, we’ll go there, we’ll ring the doorbell because the house is no longer in the family, and we’ll ask that they let us rummage through stuff in the attic. And we’ll find the box with Batya’s manuscripts. But I somehow doubt very much that it’s ever going to happen.”

EL: In “Kinship,” you end the poem by cursing the “bedlamite who dispatched the Russian troops / To annihilate Ukraine, to die on my ancestor’s native land.” So that’s Ukraine. Whom do you curse in the situation of Israel and Palestine, where you have cultural and familial ties as well?

MDS: “The poem ‘Kinship’ does not specifically deal with Israel and October 7 because it predates it. In the poem I curse Putin’s regime and his generals. But in the current conflict I curse Hamas, its leaders, its murderous members and enablers. I have various feelings about the conflict, colored by my sense of identity and belonging, but curse is something I specifically reserve for Hamas … Poetry is anything but impartial. It’s the most partial of arts because it forces you to choose a very specific place in the universe, and to express your connection to this place in a very specific way through language … I can curse Putin for trying to murder Ukraine, and I can curse Hamas, an organization whose charter is about murdering Israel. But I would never curse a whole nation of people, or a whole identity or community; I just don’t think this way.”

EL: What happened after the book was finished and Oct. 7 happened?

MDS: “The book was already under contract, and the publication date was already set. The book had already happened in my mind, and now it was a matter of it coming into the world. I have been writing very intensively since Oct. 7, in both Russian and English, and I now have new, forthcoming collections of poems directly connected with it. Oct. 7 changed me, but it cannot post factum change my previous books.”

EL: It must have been challenging to finish this book about your identity and then have that happen.

MDS: “Yes, but my angst and my anger after the Hamas attack are a different story for a different book. Let’s speculate for a moment. I think that people who, in the post-Oct. 7 climate, have become hostile to Israel, probably are not going to want to read a book where Israel plays a significant and positive part. I cannot control that; I can only regret the narrowness of some minds. But I think there are readers who have developed a new interest in these questions, and perhaps will look to my book to find some explanations and answers, because of course one of the biggest problems we’re dealing with is ignorance about things Jewish and Israeli. There are poems in ‘Kinship’ that could explain to the readers what kind of a beautiful and complex place Israel is, and that’s certainly one of my hopes.”

“There are poems in ‘Kinship’ that could explain to the readers what kind of a beautiful and complex place Israel is, and that’s certainly one of my hopes.”

EL: In the cycle “Eretz Yisrael” you describe experiences at the Western Wall with your young daughter, where your presence reassures her. Can you tell me more about what made you choose to include that story?

MDS: “This is about my younger daughter Tatiana, who is now 17 and who is a published poet, a fourth generation poet in our family. It was Tatiana’s first visit to Israel, she was around seven, and she had this idea that she wanted to look like a girl from a very religious family. And so we bought her a long black skirt from a shop in a section of Jerusalem populated by ultra-Orthodox Jews.”

“How the Wailing Wall—the Kotel—works is that you meander through the old city of Jerusalem, and eventually you make your way to this big open space and you see what remains of the Temple, probably the holiest site in Judaism. And beyond it you see the Dome of the Rock, which is one of the holiest places in Islam. You see a crowd of Jewish pilgrims and as they approach, women go to the right and men go to the left, because in traditional Judaism, men and women don’t sit together in synagogue. And so Tatiana and I were approaching the partition, and she was a little kid and I sensed that she didn’t want to go alone. And I wasn’t exactly keen for her to be alone in a sea of people. So I said, just walk with me. But somehow as we were walking, I was thinking to myself that to G-d, gender is perhaps only of some relevance, and certainly not in the way that would separate a father and a young daughter. And so we got to the Kotel and wrote notes. And of course, the notes are not for the reader, the notes are for G-d. In an earlier draft, I had actually the text of our notes. But then I just left dots. You can write your own note, in your head. And, of course, the cycle is referencing a much more peaceful time in Israel. What I’ve been writing since is a very different reflection, and it will be in my next book, to be titled ‘Zion Square.’”

EL: I personally loved the imagery you created in “The Bombing of Odessa,” where the “poets and sages come to its rescue.” Can you tell me more about how you assigned a weapon to each of them?

MDS: “Odessa is a very special city. It’s the last great city of the Russian Empire. The ambition of Catherine the Great was to build a great southern port city, and Odessa was quickly built in the 18th century. It has always had a large Russian, a Ukrainian, a Jewish and a Greek community, but it had many other ethnicities and languages, a truly multicultural, multireligious, multilingual city. A very cosmopolitan city. Many talented writers, artists, composers, performers came from Odessa. In Odessa many different poets once coexisted, writing in different languages and sharing the Odessan identity. When Putin’s troops started bombing Odessa, I remember thinking, this is urbicide. And I had this idea that poets come to the rescue of their city. I thought of various poets who had lived in Odessa over the years. In my poem about the bombing of Odessa, there are Ukrainian poets, Russian poets, Yiddish poets, Hebrew poets, Greek poets, Tatar poets. Some poets have military experience whereas others do not, some are by inclination militant and others are passive and submissive. So I thought, well, each will use a weapon of his or her choosing. For each of the poets I reference, knowing something about their past, I chose a military occupation in today’s Odessa under Russia’s bombs. Take the poet Sasha Cherny: His family owned a pharmacy, and so I figured, he has some experience, he will make handmade explosive devices. And another one, Anna Akhmatova. Her father was a naval officer, so she would use his naval dagger. The idea is that these Odessan poets are not only voices; they are a magical defense force against Putin’s murderous troops.”

“The idea is that these Odessan poets are not only voices; they are a magical defense force against Putin’s murderous troops.”

EL: What is your hope for “Kinship” after its release?

MDS: “The book opens with an antiwar, anti-Putin poem. One of my hopes for this collection is that it would help people connect a lot of the dots. Look, we talk about the war in Ukraine. Who is fighting with whom and for what? What is at stake? I remember waking up to the news of the war in Ukraine and thinking, this is just so unbelievable, so unfair. Both of my grandfathers and a grandmother were born and grew up in Ukraine, and I, too, have a stake in this war.”

“What I’m after in the book? I truly think that there is room in our culture for more poetry that deals with the roots of some of today’s biggest conflicts. Among the people who can shed light on these conflicts are translingual poets who are between worlds, who are rooted in two worlds. Poets who, like myself, came from the former Soviet empire but have made a life here in America—and also in the English language. Some of the poems in ‘Kinship’ have a political dimension, a historical dimension that probably would require thinking, reflecting, perhaps even additional reading. And yet I don’t want this book to be thought of as primarily a political document or a pamphlet. It’s a book of lyrical Jewish poems; they are confessional and self-denuding, and that’s the best hope I have for any poem.”