I was late to the havurah movement — the egalitarian, counterculture congregations that blended grassroots spirituality, social activism and skepticism about mainstream synagogues and the Jewish establishment. By the time we joined Farbrengen in Washington, D.C. in the late 1980s, the founders of the movement were sprouting gray hairs and more than a few were leading mainstream synagogues and establishment institutions of their own.

Still, my memories of that time are unmistakably and anachronistically of the 1970s. That’s in large part thanks to the photographs of Bill Aron. A trained sociologist and street photographer, Aron took iconic photos of his fellow members of the New York Havurah in its 1970s heyday. Many of those photos were included in “The Jewish Catalog,” a do-it-yourself guidebook created by members of the New York Havurah. Decades after it was first published in 1973, it remained a touchstone for Jews who were trying to lead the kind of hands-on, committed Jewish life that their suburban parents had put behind them.

Those images of the New York Havurah are a small but essential part of the new retrospective of Aron’s work at the Center for Jewish History, which draws on more than five decades of his work, now stored in the collections of the American Jewish Historical Society. The men, women and children in those black and white photographs are displayed between Aron’s images of Orthodox Jews on the Lower East Side in the early 1970s, and future projects showing Jews in Cuba, Russia, Los Angeles, Israel and the American South.

Bill Aron, whose early projects included a series on Jews living on New York’s Lower East Side, discusses a new exhibit of his work at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan, Feb. 4, 2026. ((JR))

Together, they offer a visual conversation between tradition and reinvention — a theme of Jewish diversity that animates his work. While the havurah might have its roots in the tie-dyed 1960s, Aron’s work suggests that being Jewish is itself a counterculture.

“The complexity makes us all part of the American Jewish experience,” Aron said last week, leading a press tour of the exhibit. “There are all different kinds of Jews who look different and behave differently.”

There are, for example, two photographs of Jewish scribes, an island and worlds apart. The first, identified as “Rabbi Eisenbach,” was shot on the Lower East Side in 1975 and shows a haredi Orthodox man with a lavish white beard and a quill pen, hunched over an unscrolled Torah.

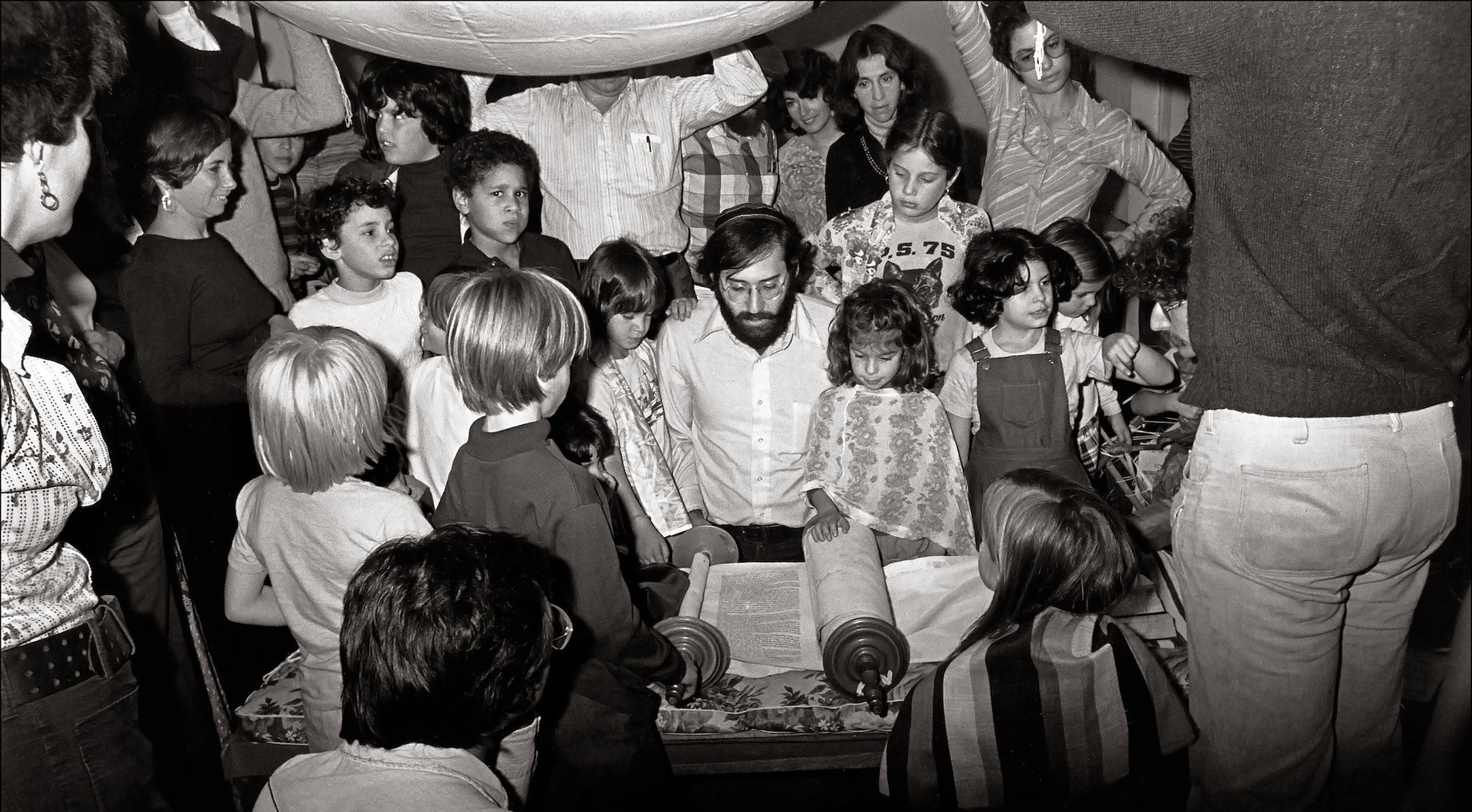

In the second, taken at the New York Havurah Shabbat School on the Upper West Side a year later, children in T-shirts and overalls surround a young Jay Greenspan as he reads from the Torah. Greenspan, who died in 2017 at age 69, led a revival of traditional Jewish scribal arts in the havurah movement and beyond, closing the gap between Jewish worlds that had begun to drift apart.

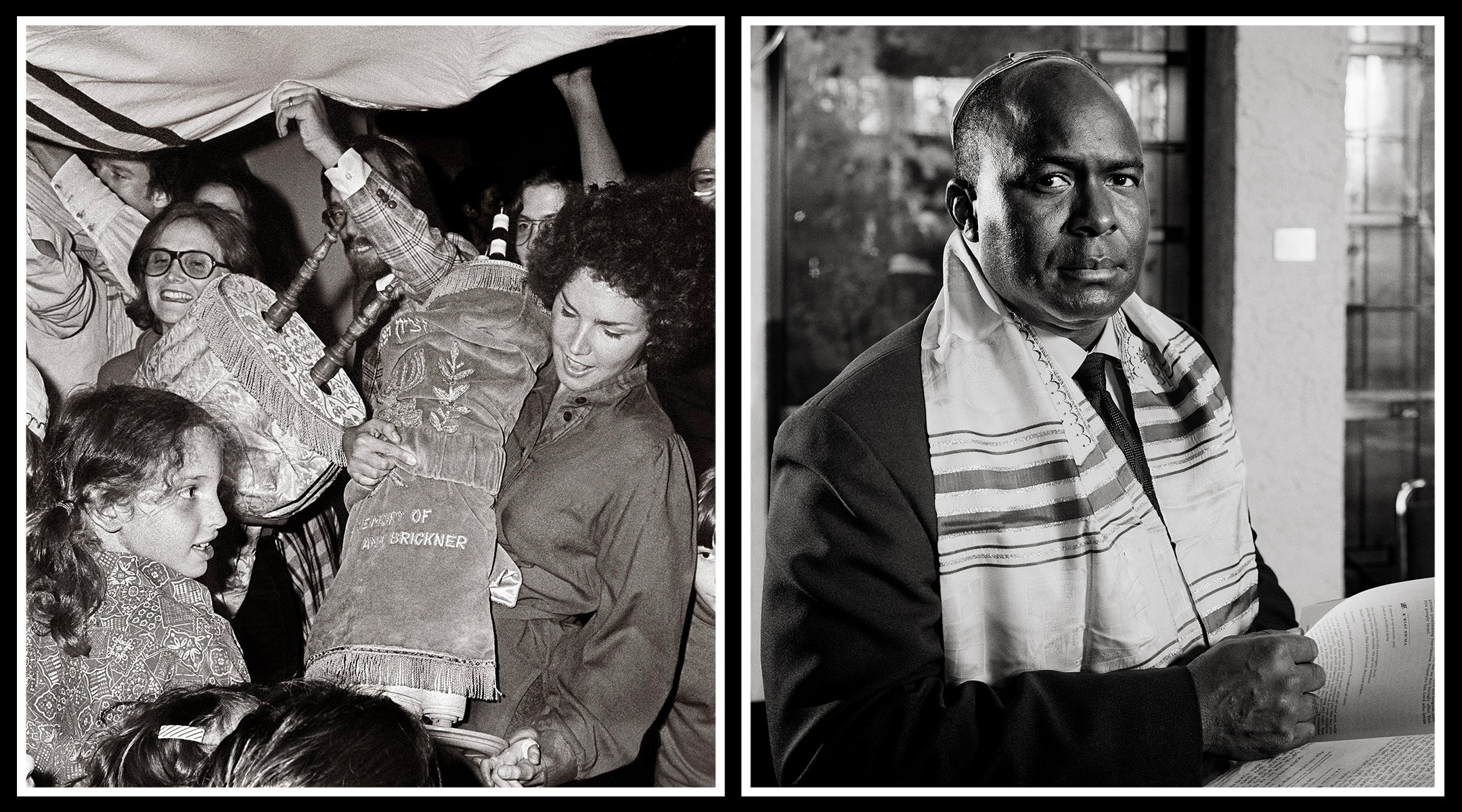

In another image, reproduced frequently in books and articles about Jewish feminism, Judith Samuels and other women dance with Torah scrolls on Simchat Torah. (Samuels, a social worker, was a member of the Jewish women’s feminist group Ezrat Nashim.)

Left, “New York Havurah Simchat Torah: Judy Samuels Meirowitz Tischler, 1976.” At right, “Police Chief Reuben Greenberg, Charleston, S.C., 2000.” (Bill Aron, American Jewish Historical Society)

“I didn’t grow up particularly religious, but I was fascinated by these different expressions of being Jewish,” explained Aron, a neat and trim 84-year-old. His wife Isa introduced him to the New York Havurah, where she and Greenspan helped found its school. Isa Aron went on to become a professor of education at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles, where the couple live.

“It was magical,” he said of the six years they lived in New York and the community surrounding the havurah. “The Boston havurah was known as the spiritual one, Washington’s was known as the political one, and we were known as the eating one.”

Although he earned a PhD in sociology at the University of Chicago and later did research at a California state hospital, Aron found his true calling by photographing Jewish life for various nonprofits, including the Project Ezra anti-poverty group and what is now the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life.

Each of the photos prompts a story — of the elderly Holocaust survivor who planted a fat kiss on his wife’s cheek, of the yeshiva head who overruled his bodyguards and let Aron snap a photo of him buying an etrog. For his “Shalom Y’all” project on Southern Jewry, he shot a regal image of the late Reuben Greenberg, the first Black police chief of Charleston, South Carolina, who told Aron how he came to convert to Judaism.

The exhibit is a visual archive of late-20th-century Jewish life: rural congregations and urban streets, intimate family moments and mass gatherings like a pro-Israel rally at the U.N. It’s also a bit wistful. Aron captured the Jewish communities of the Lower East Side and the American South when both were in decline, although the former would bounce back with a new generation of Modern Orthodox Jews, gentrifiers and nostalgists.

“To 16th Street, New York City (Hassid in Subway)” Aron documented Jewish life on the Lower East Side after he moved to the city in 1974. (Bill Aron, American Jewish Historical Society)

Despite its elegiac tone, the exhibit offers a glimpse into the energy of movements like the havurah, whose DIY spirituality feels newly relevant amid contemporary searches for meaning and community. The photographs capture moments when American Jews were asking the perennial question: What could tradition look like in a changing world?

“What binds them is that they practice their Judaism and their values, even if in different ways,” Aron said.

“The World in Front of Me” runs through June 4 at the Center for Jewish History,

15 West 16th Street, New York, New York.