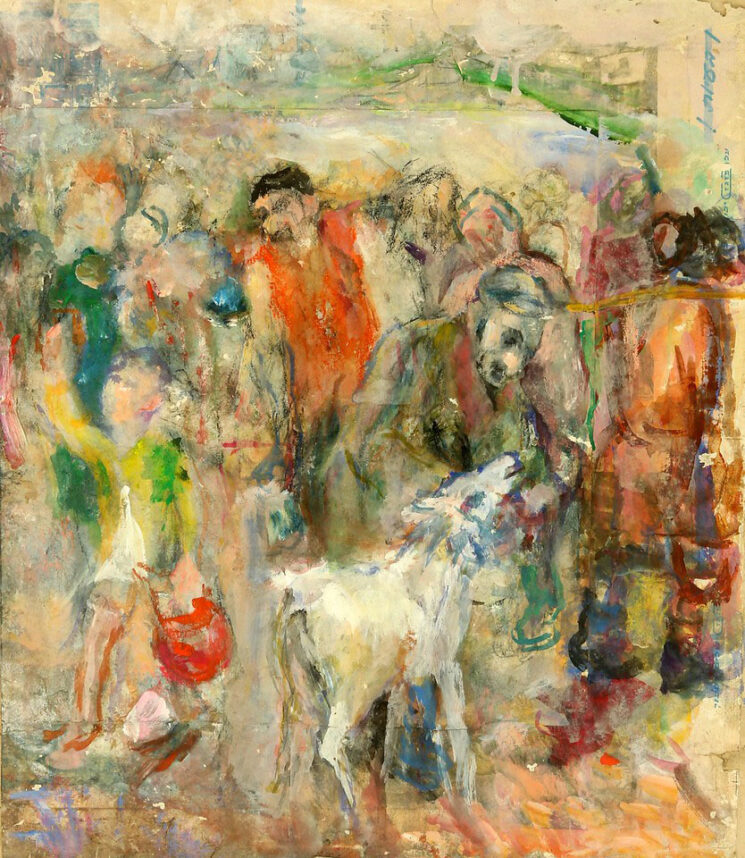

When Fiddler on the Roof was staged at The Soraya at CSUN, audiences encountered more than Sholom Aleichem’s beloved characters brought to life on stage. Alongside the production, the David Labkovski Project presented ‘Through the Eyes of David Labkovski: Sholom Aleichem and His Heroes,’ an exhibition that offered a visual journey into the shtetl world Aleichem immortalized in his stories.

Labkovski himself was born in Vilna, Lithuania, and endured extraordinary hardship. Arrested and sentenced to Siberia as an “enemy of the State,” he survived the brutal conditions there in part through his art. When he returned home after the war, Vilna—once a thriving center of Jewish culture—lay in ruins. He stayed there for 14 more years and in 1958 he immigrated to Israel, where he continued to paint, determined to preserve not only the destruction he had witnessed but also the richness of Jewish life that had been lost. Those were the same landscapes that Aleichem described so vividly and lovingly in his stories.

Leora Raikin, the great-niece of Labkovski, became very close with her great uncle and great aunt as the two didn’t have any children of their own. She told the Journal they were more like grandparents to her. Wanting to commemorate his legacy, she embarked with the David Labkovski Project (DLP) in 2016. She started working with de Toledo High School students and installed the first exhibit at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust.

The educational initiative offers a unique approach to combating antisemitism and education about the Holocaust. It integrates history and art, empowering students with the skills to educate their peers and community. Through the artist’s paintings and sketches, viewers not only learn about the Holocaust but also lessons of life, survival, tolerance, acceptance and the importance of bearing witness to history.

The juxtaposition of Aleichem’s literary voices with Labkovski’s painted visions created a poignant dialogue between text, performance, and image. Though the performances have ended, the exhibit remains open, offering students and visitors the chance to reflect on the vibrancy of a world that once was, and on the enduring power of art to bear witness.

Raikin believes that her great-uncle’s art allows visitors at The Soraya to understand Jewish life both before and after the war.

“Through his art, you see what life looked like before and after the Holocaust—how people worked, dressed, and lived, all in vivid color,” said Raikin. “There is a generational element in connecting Sholom Aleichem’s world through Labkovski’s art.”

The classic musical Fiddler on the Roof, first performed on Broadway in 1964, went on to win nine Tony Awards. The popular show drew on universal themes of changing times and a household torn by young love. But the reality behind the production was not so simple. Tensions flared between lead actor Zero Mostel and director-choreographer Jerome Robbins, divided in part by their opposing views on the House Un-American Activities Committee. Some critics also faulted the musical for “whitewashing” Sholem Aleichem’s original stories, softening their depictions of Jewish persecution in Eastern Europe.

In 2018, the New York–based National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene reclaimed Fiddler as a deeply Jewish story, translating the script and lyrics into Yiddish, with English supertitles. They assembled a top-tier Broadway cast led by Steven Skybell as Tevye. The results were historic—praised as fresh, authentic, and profoundly moving. New York Times critic Jesse Green wrote, “Even the jokes were making me cry.”

After pandemic-related delays, the Folksbiene finally brought Fiddler on the Roof to the West Coast in a special concert version, performed September 13–14, with Steven Skybell once again reprising his leading role.

One of the performers, soprano and part-time personal trainer Jessica Fishenfeld, told the Journal she was thrilled to be part of the production. Like many of her castmates, she does not speak Yiddish, but learned to sing in the language.

“As an opera singer, I’m used to singing in languages I don’t speak,” she explained. “I sing in German all the time, and Yiddish is actually pretty close. You learn it word by word with the phonetic translation. If you just translate literally, it won’t make sense in English, so you really have to learn the music of the words.”

Labkovski developed a remarkable affinity for Aleichem’s writing, creating a complete series of illustrations for the author’s centennial.

Raikin added that many people don’t realize that Tevye the dairyman, the central character of Fiddler, originated in Aleichem’s stories about his daughters. Labkovski’s illustrations of these tales offer not just images but a visual narrative of Jewish life in Eastern Europe before its destruction.

“It serves as a cultural bridge to the wider community, because obviously not only Jewish audience would come to watch Fiddler on the Roof,” said Raikin. “This is education through art about that period of time. Students will be able to come on field trips, see the paintings, and place themselves within the stories. It’s a multigenerational experience that brings people together and exposes them to the art and the wonderful stories of Sholom Aleichem.”