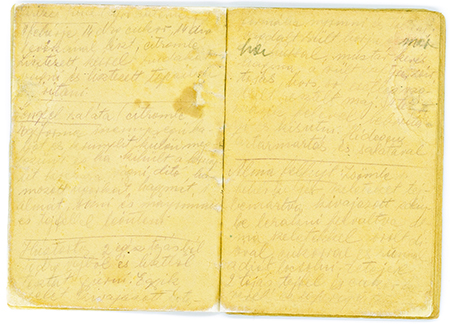

Photo Credit: Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection, donated by Elhanan Ejbuszyc, Israel

Artifacts from the Holocaust – which arguably began on Kristallnacht 81 years ago this Shabbos – provide us with an intimate link to the Jews who lived through those horrific years. By the items they left behind, we draw closer to them, and we shudder as we realize we could have been them had we been born a few generations ago.

The artifacts below represent slivers of normalcy and sparks of hope amidst terrible darkness. In many cases, they were the only remnants of regular life for their owners. Jews in concentration camps sometimes created them and held onto them as a survival mechanism – to cope and mentally escape.

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 0 });

1. Chess as a Tool for Peace (above): Elhanan Ejbuszyc, a professional carver, was confined to a block in Auschwitz-Birkenau run by a vicious, sadistic Nazi who beat Jewish prisoners and later spent the rest of his life in prison for allegedly murdering his own family.

This evil prison leader liked to boast about his impressive chess skills, which gave Elhanan the bold idea of asking him if he could carve chess pieces out of his club. Shockingly, the prison leader gave him his club and even handed Elhanan a pocketknife along with it.

There was one caveat, though: If Elhanan failed to finish the project within four days, he would be killed. Elhanan’s life was quite literally in his own hands. Before his time was up, Elhanan was transferred to the Goerlitz labor camp. On his way there, he tucked the knife, chess pieces, and remnants of the club safely in his pocket.

For Jews in concentration camps, playing chess was much more than a pastime; it was a temporary escape from foreboding circumstances and a rare, treasured opportunity to bond with other prisoners. Elhanan poignantly illustrates the crucial role chess played for him during this period:

“[W]hat I achieved – turning a tool of punishment into a tool of peace after breaking it into pieces and carving chess pieces from it – was to give my fellow Jews a rare chance to forget their pitiful circumstances for a while. That brief moment of solace that I managed to bring to my fellow sufferers filled me with such joy – this was my reward…” (“Bearing Witness – Stories Behind the Artifacts in the Yad Vashem Museum Collection”).

Elhanan Ejbuszyc was liberated by the Russians in 1945. His chess pieces are featured in a Yad Vasham exhibit titled “Chess Sets, a Brief Respite from a Harsh Reality.”

2. Dream Recipes: In 1938, at age 24, Yehudit (Aufrichtig) Taube left her birthplace of Hungary to immigrate to Amsterdam, where she studied to become a beautician while working as a nanny for a Jewish family. Two years later, the German army occupied Amsterdam, and the wife of a Hungarian ambassador provided Yehudit with a fake passport to conceal her Jewish identity.

Yehudit joined the resistance and surreptitiously helped Jewish families in hiding by giving them food and ration cards. In 1944, Yehudit’s life suddenly changed when a Dutch woman exposed her activities. She was deported to Westerbork, a concentration camp in the Netherlands, and then to Ravensbrück in Germany.

Yehudit and her friends were forced to work at a factory nearby where they would dream up recipes of delicious gourmet dishes they wished they could eat. Talking about cooking and preparing these meals united them. It also served as an escape that gave them hope and something to look forward to amidst their bleak and desolate reality. They tried their best to record as many recipes as they could. Yehudit fondly remembers:

“We had low quality white paper. We took out a large sheet and folded it into small pieces. I brought a thread and a needle and sewed it so that it would not come apart, and we wrote in it. … The objective was to satiate our need for food. If you are hungry you don’t care about anything but food.”

Yehudit’s recipe book is featured in the Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection. She passed away in Israel in 2003.

3. The Fateful Day When Time Stood Still: In 1944, Benjamin Anolik and his brother Nissan were taken to the Klooga labor camp in German-occupied Estonia. They were young adults who should have had futures of endless possibilities to look forward to, but instead they witnessed horror, unimaginable cruelty, and senseless tragedy.

The Red Army was approaching, and the Nazis wanted to murder all of the Jewish prisoners. The day after he arrived at Klooga, Benjamin saw 2,500 prisoners “sitting cross-legged on the ground with their hands on their heads.”

His uncle, Dr. Włodzimierz Poczter, was among this group of Jews who had been taken to the forest to be killed. “Uncle Poczter stepped out of line and approached my brother with his pocket watch and told him: ‘Take the watch, I won’t be needing it anymore.’”

Benjamin and Nissan found an abandoned building to hide in. They heard gunfire blasting as the Red Army came to finally liberate the Jewish prisoners.

Dr. Włodzimierz Poczter died with a picture of himself and his family lovingly tucked in his pocket.

4. A Reminder of Innocence: An unimaginable 1.5 million children had their lives cut short in the Holocaust. For children who were rounded up, separated from their families, and forced to go to concentration camps, holding onto a doll or playing with a toy may have been one of the only fleeting moments of normalcy they had.

Before World War II broke out, Zofia Chorowicz Burowska’s parents gave her a cherubic-looking, brown-haired doll wearing a peach-colored dress. She kept it with her when she lived in the Wolbrum and Krakow ghettos in Poland, then gave it to a non-Jewish friend for safekeeping before she was deported to two forced-labor camps in Poland.

She was liberated from the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany, and after the war ended, she went back to Krakow to find her doll.

Dr. Zofia Burowska donated her doll to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 25 });