HAIFA — On a recent chilly morning, six Israeli Druze women gathered in a room at the University of Haifa library to discuss the joys and frustrations of living in a modern, Jewish, largely secular country.

Chatting in Arabic and Hebrew, many of the women, all students at the university, spoke about the challenges of balancing their traditional Druze identity with their modern Israeli aspirations.

“I spend two hours each way to come to school. But my education is so important, I’d do it even if I spent 10 hours a day,” said Walaa Bader, 20, an Arabic literature and music major from Horfeish, a Druze village of some 6,000 souls near the Lebanese border.

Adan Bader, 22, said she became secular four years ago in part to focus on her studies.

“I was a religious girl, but our religion doesn’t encourage young women to study,” she said. “At this stage of my life, I wasn’t ready for a full commitment to my religion.”

The get-together was part of a series of weekly meetings organized by Yael Granot, director of social engagement at the University of Haifa’s student dean office. It’s part of the university’s larger social and educational mission: to serve Israel’s Arab population and build bridges between Israeli Arabs and Jews.

Aside from being a world-class center for higher learning with over 18,000 students, the university runs various coexistence programs to facilitate dialogue and mutual respect between Jewish and Arab students. One is the Jewish-Arab Community Leadership Program, which facilitates dialogue and multicultural social interaction through joint community projects.

“In addition to creating scientific knowledge, our main mission is the expansion of professional opportunities for all members of society,” University of Haifa President Ron Robin said when he began his tenure as president. “We embrace the rich tapestry of communities that make up Israeli society.”

Approximately 40% of the university’s students are Arabs, including some 300-400 Druze women. Druze constitute an Arabic-speaking faith group with some 150,000 adherents in Israel, most of whom live in highly conservative villages in northern Israel. About 70% of all Arab students at the University of Haifa are women.

“We’re very proud to be Druze, and very proud to be Israeli,” said Bader. “But we are doubly marginalized because, even within the Arab minority, we’re not Muslims. And the Basic Law puts a question mark on our sense of belonging to Israeli society,” she said, referring to a 2018 law enshrining Israel’s identity as a Jewish state that many Arab Israelis complained relegated them to second-class status.

Granot sees her role as helping the Druze students balance their personal backgrounds with their academic and professional interests. The Druze women in her group recently created mentoring groups for Druze teenagers to encourage them to pursue higher education.

This approach is part and parcel of the university’s mantra of “thinking locally and acting globally.”

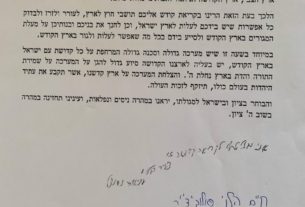

Druze high school students discuss “soft skills” with University of Haifa student mentors during a weekly meeting in the northern Galilee village of Horfeish, Israel. (Amal Merey)

On the local level, the university is trying to create a new broad and inclusive middle class. Its campus, located in a part of Israel with significant Jewish and Arab populations, strives to serve as an oasis of coexistence. Among the university’s joint community projects is Hai-fa Innovation Labs, a start-up incubator whose programs focus on social innovation and impact entrepreneurship.

On the global level, this university located on the Carmel mountains with sweeping views of the Mediterranean Sea has a strong research focus on the environment. At the university’s Leon H. Charney School of Marine Sciences, scientists are studying how to improve seawater desalination — a major source of Israel’s water supply. Among the elements most critical to sustainable desalination, experts say, are ensuring the quality of drinking water while reducing byproducts of the desalination process. The school is actively monitoring these issues to protect Israel’s coastal and marine environments and provide guidance globally for how to replicate successes worldwide.

The university’s Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies is partnering with the Scripps Center for Marine Archeology at the University of California San Diego to investigate the long-term impacts of climate change and rising sea levels in the eastern Mediterranean.

Students and scientists at the Charney school are exploring the viability of using ocean plants as sustainable food sources to meet the needs of the globe’s rapidly expanding human population.

As the university celebrates its 50 th year, it has aligned its academic strategic plan with the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aimed at eliminating poverty, hunger and discrimination worldwide.

On a concrete level, the university has mounted a $150 million fundraising campaign to build infrastructure, expand research areas and update its technology.

Back in Granot’s group, students are figuring out their own ways to effect change.

“We put a great emphasis on providing tools for social entrepreneurship and letting students work and find their own voice for social change,” Granot said.

In one initiative, the group asked 15 local Israeli municipalities to identify a cause or problem they’d like the students to tackle.

In Acre, a city in northern Israeli that saw violence break out between Arabs and Jews during Israel’s 2021 conflict with Hamas in Gaza, 10 students — five Arabs and five Jews — worked together to map out challenges. They came up with a plan in which Jewish and Arab youth in Acre would create joint tours in Hebrew and Arabic for local schools. The students get about $2,850 each for their participation and are expected to volunteer 140 hours a year. The tours are expected to begin in the coming months.

The university also has enlisted two institutions, Beit HaGefen and the Boston-Haifa Partnership, for a project in which students are encouraged to utilize their creativity, activism and aspirations to design initiatives and opportunities for shared spaces in Haifa. In the program, 15 students of diverse backgrounds — native-born Israeli Jews, Arabs, Christians and Druze, as well as new immigrants from Russia, Ukraine and Ethiopia — meet on Tuesdays with local entrepreneurs while conducting tours of Haifa.

“Our main objective is to get them to know their city, with all its challenges and complexities, and make them into active citizens working toward social change,” Granot said. “Even people born here don’t really understand the richness of this city. We’d like them to experience that.”