Boris Gorbis can talk for hours about what turned him into a collector. At 74, he has amassed what is likely the world’s largest assemblage of Zionist souvenirs — mass-produced menorahs, napkin holders, seder plates, plaques, and other mid-century tchotchkes from Israel that once filled American Jewish homes but have since been discarded or forgotten.

To explain the roots of his obsession with Israeliana, he’ll weave together Jewish lore, philosophy and bursts of self-psychoanalysis. But then, interrupting his own pontificating with a flash of blunt candor, he lands on the truest and most immediate cause.

It was a singular moment in the 1980s, when he was gathering old menorahs for a Hanukkah program in Los Angeles and stumbled upon one particular candle holder.

The menorah’s brilliant emerald-green color dazzled him, as did its form: The candles rested atop a base shaped like a fist — the symbol of Lehi, a Zionist paramilitary group from Israel’s pre-state years.

“I may not remember my first orgasm, but I remember the first sense of penetration — of whatever it stood for, whatever it meant, whatever it was aesthetically,” Gorbis said in an interview. “That was it. That set up everything that would follow.”

What would follow: an accumulation of hundreds of thousands of items that have overtaken Gorbis’ Hollywood Hills mansion (and a rented storage space) and set him on a now-urgent mission. He aims to find a home that can outlive him for a collection that recalls a bygone era in Jewish history, a challenge made all the harder by a political climate shaped by the war in Gaza.

“A full-throttled exhibition about Zionist paraphernalia right now? I don’t see it happening,” said Jenna Weissman Joselit, a historian of American Jewish life and material culture at George Washington University. “And if it did, I could only dimly imagine the reception it would receive.”

***

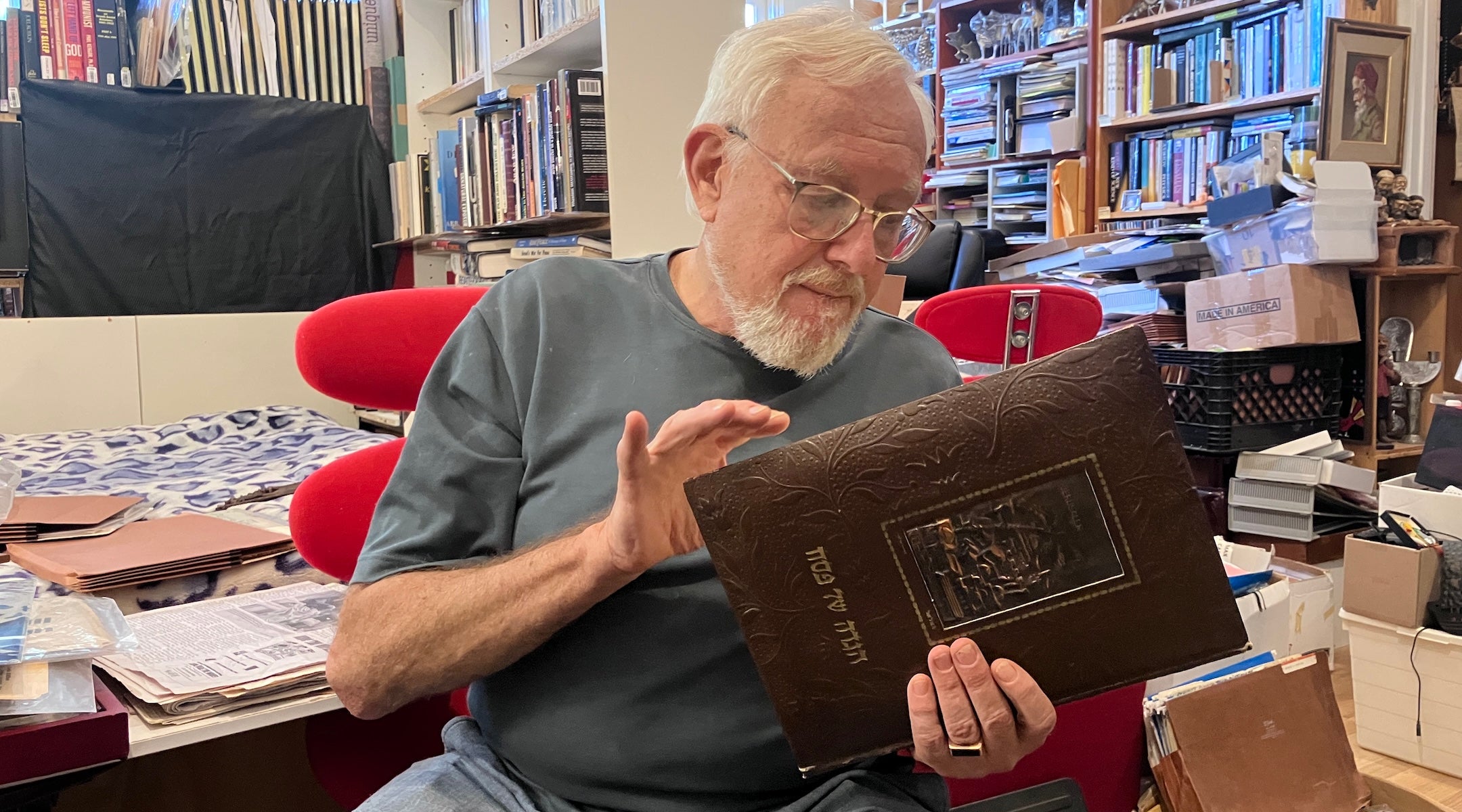

Boris Gorbis’s Hollywood Hills home is packed with thousands of discarded Israeli tchotchkes. (Asaf Elia-Shalev)

Still, while Gorbis’s awe at the emerald-green menorah might seem personal or eccentric, scholars of Jewish material culture say he was responding to a broader aesthetic that once held real cultural power.

In the decades after Israel’s founding, souvenirs cast in alloy and painted in faux-patinated green to look like copper or bronze were widely collected by American Jews. Joselit explained that these objects were intentionally designed to feel ancient and modern at the same time.

“These objects harked back to King Solomon’s copper mines, but were constructed with a very modern geometry,” Joselit said. “It’s a perfect symbol of this new construct of Israel that isn’t so new in many ways. Israel played on these currents, presenting itself as phoenix. And people wanted a little piece of that romance for themselves.”

On visits to a new country in an ancient land, Americans filled their suitcases with all manner of bric-a-brac: matchbooks from the restaurants they visited, postcards showing landmarks they defied history to set eyes upon, ashtrays and coasters lavished with grapes, olives and lions, icons of a people reborn.

Gorbis’s collection totals an estimated 200,000 items, including ephemera like historical photographs, documents and musical records.

Few of the items are worth much on their own. Many of the relics were mass-produced in Israeli workshops and meant for sale as tourist paraphernalia for American Jewish visitors. Gorbis scavenged the items one at a time from thrift stores, garage sales, and, later, eBay. All together, however, these long-ago discarded items tell what Gorbis considers a monumental but forgotten story.

“It’s evidence of the love affair that existed between Americans and the entire idea of a Jewish home,” Gorbis said, lamenting what he sees as today’s less enchanted relationship between Israel and the Diaspora.

And yet Gorbis is not the only one who cares. A small but dedicated group of collectors and scholars have begun to take these objects seriously, not despite their kitsch value, but because of it.

Rachael Goldman, a professional appraiser and historian, has spent years researching the origins and makers of these souvenirs. She has identified and cataloged more than 30 companies that once produced this material, names like Pal Bell, Dayagi-Hen Holon, Fantasia and Hakuli.

“It’s hands down the best collection I’ve heard of,” she said of Gorbis’s trove.

Still, Goldman acknowledges that the very qualities that made these items accessible and beloved in their time might now make it difficult to generate institutional interest.

“These pieces were not made for the purposes of being displayed in a museum,” she said. “They were made for the tourist trade, and they were made for utilitarian purposes.”

Handcrafted figurines, depicting biblical characters from Gorbis’ collection. (Asaf Elia-Shalev)

***

I met Boris Gorbis last year after receiving a strange phone call one morning.

The caller, Micha Keynan, introduced himself as a fellow writer and an Israeli, like me, living in Los Angeles. What he said next sounded like a cryptic business proposition.

Citing a few stories I’d written about Jewish museums, Keynan said he had a wealthy acquaintance who needed help. I’d never heard of Boris Gorbis, but according to Keynan, he was well-known in the local Jewish community, a retired lawyer who lived in a Hollywood Hills mansion, and owned a vast collection of Israeli tchotchkes.

“He’s looking to sell his collection to a museum,” Keynan said. “Maybe you have useful connections?”

“I don’t know anything about brokering deals between collectors and cultural institutions,” I told him, “but I’m curious — as a journalist.”

It was hard for me to imagine what exactly these tchotchkes were or what they might be worth, but I had some notion of which museums could be interested in them.

“Why don’t you just go visit him?” Keynan asked.

Gorbis’s desire in his accruing age to find a permanent home for his collection raised a universal challenge that eventually comes to almost every person: What happens to our stuff after we die? Particularly when, as is so often the case, it is simultaneously invaluable but not very valuable at all? Trying to answer that question can bring anguish and the deeper trouble of wondering what one’s legacy is worth.

I couldn’t be his agent, but I knew that, at the very least, I could use journalism — my license to ask anyone almost anything — to figure out if there’s any kind of market for Gorbis’s stuff.

Two days after talking to Keynan, I was driving down Sunset Boulevard, searching for the right-hand turn that would take me up the mountain to Gorbis’s house. My 15 minutes navigating steep and windy roads, narrowly avoiding collision with an oncoming pickup, were rewarded with classic Hollywood panoramas.

Gorbis’s house is located on a hillside sloping down from the road, which makes it look small from the street, nothing like what Keynan had suggested. But the door was ajar, and once I knocked gently and stepped inside, I saw the house was cavernous, an effect enhanced by massive windows that opened into a canyon.

A vintage menorah from Israel’s early years. (Asaf Elia-Shalev)

Art was everywhere, but before I could focus my eyes on any one piece, a housekeeper appeared and directed me to a spiral staircase. After descending, I heard my name being called and followed the voice down a dark corridor until I reached what looked like a storage room but was actually a bedroom.

Gorbis sleeps surrounded by bookshelves, cabinets and tables packed with books and artifacts, with only a narrow access point for him to get in or out. His poor health has limited his mobility, so the bedroom is where he receives visitors like me. It’s where he smokes cigarettes, does his art projects (figurines assembled from miscellaneous plastic parts) and dines. Later, he would share with me a meal of fresh fruit and buttered bread with cured salmon.

Gorbis spoke with a slight Old World accent and wore a simple T-shirt, but the way he styled his bright white hair and beard hinted at a lifetime of more formal wear.

He shared the story of his collection and how he used to run something he called the America-Israel Museum out of a law office housed in what was once the headquarters of Hustler publisher Larry Flynt, a juxtaposition that Gorbis seemed to find amusing rather than incongruous. His lease ran out years ago, and most of the collection is now in storage.

He then explained why he invited me over.

“I felt passionately consumed by protecting these things and preserving them, bringing them in one space, believing against all evidence that I’m doing the job that should have been done and that people will see how necessary it was,” he said. “Boy, was I mistaken.”

It turned out that I represented his last-ditch effort to get someone to care.

“In the 30 or so years that I’ve been doing this, for reasons I cannot comprehend, I could not create alliances,” he said. “All the appeals, all the letters I wrote to Danny Danon [Israel’s ambassador to the U.N.] and Reuven Rivlin [its former president] and others. The worst part of it, I didn’t get a single response, not even an acknowledgement.”

***

Passionate collectors with compelling personal visions are essential for cultural preservation, but that doesn’t always translate into institutional acquisition, according to Josh Perelman, senior advisor and former chief curator at the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

With the disclaimer that he didn’t have enough information to opine on Gorbis’s material, Perelman said collections like his can hold deep emotional and cultural resonance, and reflect aspects of American Jewish identity and the relationship with Israel that are worth preserving.

But for museums, practical concerns often get in the way: limited storage, finite staffing and the need to align with curatorial priorities.

“Agreeing to take something into the museum’s collection is a commitment to preservation in perpetuity,” Perelman said.

Despite the perceived lack of interest from institutions and decision-makers, there’s intellectual validation for Gorbis in the corners of academia that take everyday Jewish material culture seriously.

“These aren’t rare objects,” said Laura Arnold Leibman, a historian of Jewish material culture and the president of the Association for Jewish Studies. “But that’s exactly what makes them powerful. They show us how ordinary Jews once expressed identity in daily life, not in a synagogue, but at the breakfast table or in a guest room. That’s what most archives leave out.”

As an example of such an item, one that wouldn’t normally be preserved or readily fit into a museum collection, Leibman brought up a small silver teaspoon that her grandmother brought back from Israel in the 1950s.

“It was just a little piece of junk that somebody brought back from Israel,” she said. “But for me it’s more than that. It’s my grandmother saying, ‘This is part of who I am.’ It’s an object that signifies that she thought it was worth remembering.”

The next generation inherits not just the object but the dilemma of what is worth preserving.

“Many people like me, when they’re taking apart their parents’ or their grandparents’ houses and sorting through everything, face these questions,” Leibman said. “Of the countless objects in my grandparents’ house, how do I decide which to keep and pass on?”

Metal bookends featuring figures blowing shofars, evoking ancient Jewish ceremonial tradition. (Asaf Elia-Shalev)

***

Gorbis opted for maximalism, an outcome he regards as a “paradox,” given his life’s trajectory.

Born and raised in the Ukrainian city of Odessa, Gorbis belongs to a large wave of Jews who left the Soviet Union in the early 1970s after the country lifted the ban on Jewish emigration. At a way station in Vienna, he was given a choice between Israel and the United States.

“I really didn’t feel like being in another collectivist paradise and paying a price for belonging,” he said, referring to the cynical view he had of Israel’s early utopian ethos associated with labor Zionism and the kibbutz movement. So he chose the United States.

In his country of origin, Gorbis studied nuclear engineering and linguistics, specializing in the history and literature of Romance and Germanic languages. After immigrating to the United States, he became a lawyer, beginning his practice in 1980, the same year he was naturalized as a U.S. citizen. He specialized in consumer rights and personal injury cases.

Gorbis scavenged his collection from garage sales, thrift stores, and eBay. (Asaf Elia-Shalev)

He met his wife, Eda, an immigrant from Tbilisi, Georgia, then also part of the Soviet Union, in Los Angeles. She is a clinical psychologist known for treating anxiety disorders, particularly obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. They have two sons.

With fluent, American-accented English, a BMW and a law office in Beverly Hills, Gorbis was held up in several 1980s news articles as an example of a well-assimilated Soviet immigrant. He spoke out against stereotypes linking Russian-speaking immigrants to organized crime and advocated for Jewish immigrants from the Soviet Union, working pro bono on asylum cases.

In 1980, he joined an effort to launch a cable network dedicated to Jewish audiences. Later, he helped found the Chabad Russian Synagogue in West Hollywood, which he once described to a reporter as a rebuke to the Soviet belief that “religion is poison.” He went on to serve on the board of the Los Angeles Jewish Community Relations Council and on the national board of the American Jewish Committee.

As he settled into life in his new country, Gorbis noticed something: American Jews were dispensing on a wholesale basis with the old knick-knacks their parents or grandparents had acquired in Israel’s early days. He tried to explain the phenomenon to himself and came up with a darker story than the one he tells today about the forgotten love affair between American Jews and Israel.

The story started with a reaction to the Holocaust: “From where I stood, it seemed that buying the items was a belated effort by American Jews to surround themselves with symbolic and tangible proof of the Jewish state’s existence in order to deal with the shame and guilt of having betrayed their European brethren.”

The children inherited the relics but not the burden, according to Gorbis’s view. “These tchotchkes did their job extinguishing a generation’s guilt and shame,” he said. “Those who came after didn’t dwell on the issue and didn’t need these sort of symbolic communicative devices anymore.”

If the heirs to these items didn’t think they were worth preserving, what made Gorbis see things differently?

Or as he put it to himself, “Having rejected belonging to Israel, what made me expend an absolutely inordinate amount of effort, time, money, resources, and derive pleasure from doing this?”

His answer arrived belatedly, after Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023 attack on Israel and the ensuing war that has challenged both the perception of Israel and the very ideals enshrined in his collection.

“I only recently admitted it to myself,” he said. “I think I was prompted to collect all this stuff by the fear that Israel is about to be wiped off, going to disappear, but some memory of it, some tangible pieces should remain.”

Keep Jewish Stories in Focus.

(JEWISH REVIEW) has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.