This is the conclusion of the interview posted last week: Zionism As A Reflection of Jewish History – Interview with Alex Ryvchin

Q: You quote a writer describing the attendees at Third Zionist Congress, including “a bearded Persian” and “an Egyptian in a fez.” Did Herzl recognize a need for Zionism among Jews in Arab lands?

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 0 });

Hertzl was the quintessential European. He possessed a rare political genius. He looked at Zionism and the Jewish Question through the prism of Europe — but he understood that for Zionism to really succeed, it had to capture the imagination of the Jewish world. It had to capture the imagination of the world leaders who could fulfill the mission of Zionism. It would have to be an international movement. He wanted to bring together as many Jewish communities as possible — even though the majority of his efforts were centered on Europe. The early Zionist Congresses set the tone for the Zionism movement that was universal. It brought together American Jewry and European Jewry and the Jews of the Middle East. and it united them in a common purpose and a common mission.

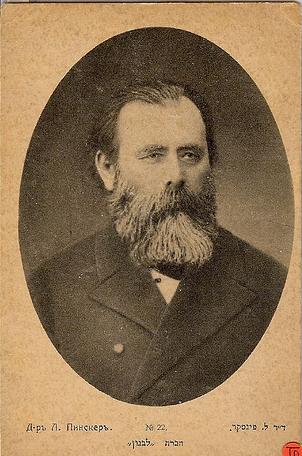

Q: Usually, we think of Herzl as the father of modern Zionism and of the Jewish state. You describe 3 men as being leading inspirations of the Zionist movement: Leon Pinsker, Theodore Herzl and Chaim Weizmann with each making a different and unique contribution to the development of Zionism. What did each contribute?

There have been many great leaders, thinkers and theorists throughout Jewish history that have sought to unify the Jewish people, but I focused on Pinsker, Herzl and Weizmann, who were very different figures and each in their own way, represent different strands of the Zionist movement.

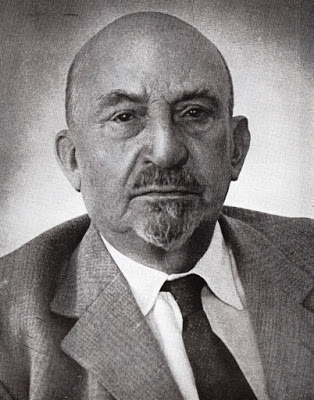

|

| Leon Pinsker. Public Domain |

Pinsker wrote a landmark seminal text, Auto-Emancipation. What was significant about Pinsker is that he came to the question as an Assimilationist. He believed fervently that by becoming fully immersed in the cultural social scientific and political life of Russia, the Jews of Europe could be saved. He believed that the sort of transformations that were happening across Europe that were granting emancipation and civil rights to Jews would eventually come to Russia. But he was rudely shaken out of his belief by the brutality of the pogroms. These did not come about as a result of peasant rage. They were deliberately and strategically incited by the very people Pinsker believed would bring the reform – the leaders, the clerics, the newspaper editors and the lawyers. His book Auto-Emancipation had a scintillating effect on Jewish thought throughout the European continent. But also, he stands for that kind of transformation from assimilation to nationalism.

|

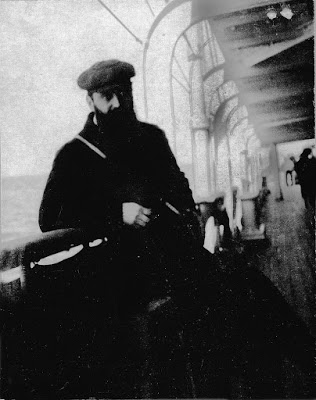

| Herzl’s visit to then-Palestine. At dawn on deck as the ship reach the shores of Jaffa. Public Domain |

Herzl was very much his successor in that regard. I spend a lot of time discussing the Dreyfus Affair. It illustrates how extraordinary and unlikely the story of Zionism is. You have the Dreyfus Affair and the story of injustice and you have 34-year-old Herzl there as the Paris correspondent for a Viennese daily newspaper, by chance observing this himself. Herzl was also an Assimilationist, to the extent that he played with the idea of converting to Christianity. He argued that Jews should disappear into the crowd. But then he sees the Dreyfus affair. He sees the public degradation and humiliation of a man who exemplified the qualities of assimilation. He was a soldier, he was civically minded and patriotic. He had given everything to the public and it culminates in his being wrongly convicted, thrown into an island prison. The mob of Frenchmen chanted “Death to Dreyfus” and “Death to Jews” outside the courtroom.

Herzl also brings something else to the story of Zionism – the idealism and the philosophy of Zionism. Pinsker had done that as well, but Herzl then converted it into extraordinary political and diplomatic outcomes in a very short period of time before his premature death. Herzl is intriguing because he shows the need to not only have great views and ideas, but also to be practical and efficient. He had a frenzied appetite for hard work. He had that Romanticism but he could also roll up his sleeves and work tirelessly.

|

| Chaim Weizmann. Public Domain |

Then you have Weizmann, who is a different type of Jew altogether. He is sort of part Pinsker and part Herzl. He comes from Russia. He moves across the continent almost the same way that Zionism moved from Russia — westward. He had been educated in Switzerland and Germany. He ends up in Great Britain where he becomes a lecturer in Organic Chemistry in Manchester. And again, in an extraordinary turn of events, Great Britain finds itself in a position where it is in desperate need of the chemical compound acetone, which when combined with gunpowder reduces the smoke generated by heavy guns in its naval battles with Germany in WWI. You wonder what that has to do with Zionism and the trajectory of the Jewish People. Weizmann is the one who discovered this formula, and through that work, he becomes associated with people like Churchill, Balfour and Lloyd George – the people who had it within their power to grant Jews their National Home. Lloyd George would later write in his memoirs that his conversations with Weizmann at this time were the origins of the Balfour Declaration.

These are 3 major figures who were possessed with a rare political genius, who have an extraordinary capacity for hard work and were able more than anyone else to transform this sort of shapeless journey to go home which the Jews had carried with them for 2,000 years and turn it into a precise political program that could be implemented.

Q: Chaim Weizmann found apparent Zionist-friendly Arab allies in Hussein ibn Ali and his son Amir Faisal — both of whom apparently accepted the idea of a Jewish state. How did we get from them to someone like the Grand Mufti who allied himself with Hitler and tried to destroy Jews and the Jewish state?

In the context of the post-WWI peacemaking, the Paris peace conference, the treaty of Versailles, the redrawing of the Middle East after the defeat of the Ottoman empire, there were a lot of negotiations between the great powers and the people who had claims to that land. So you had Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points, one of which demanded the decolonization and the autonomous development of the liberated colonies of the Ottoman empire – which was basically the Arab world, including Palestine. And then you had the native peoples of that land making claims to that land. And you have the Balfour Declaration, the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, dealmaking and promises (sometimes contradictory), happening.

In that context, Palestine was viewed as a small prize, a sparsely populated backwater, hardly the most sought after part of the Middle East. They were always willing to sacrifice Palestine in pursuit of far greater and grander post-WWI demands. That is why people made agreements with Weizmann and make statements that Jews were native sons of the land and that they should be welcomed back with open arms, that their return will have wonderful economic benefits for the Arab people living there. That is out of a view that can be seen as moderate and tolerant and willing to accept the Jewish claim to Palestine – so that their territorial claims to land elsewhere in the Middle East would be met more rapidly and more easily.

Then from the 1920’s onward, you have the tactical fulfillment of Zionism taking place. You have Jewish migration and Jewish settlement of the land, the establishment of Jewish industry, and enterprises and trade unions and newspapers and universities and wineries and all this – changing the political and economic environment in the land. Some of the Arabs living there felt dislocated and disenfranchised and what was agreed to by the Great Powers and the Arab and Jewish leaders post-WWI did not help. These are people living on the land and see their future slipping away.

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini, who would become the grand mufti of Jerusalem, was remarkably skillful – not at soothing people’s concerns and placating them and negotiating and bringing people together, and alleviating violence – he was extremely skilled at raising the temperature, and inciting people to acts of violence to his own political ends. He is the founding father of Political Islam, turning political grievances into a way to rally the whole Arab world to his cause. He is the quintessential example of the unflinching, unerring Arab leader who never negotiates, never takes a backward step, and is absolutely dogged in their anti-Zionism.

He led his people to disaster.

In 1937, the Peel Commission considered how to deal with the issue of Palestine and the competing claims to the land. The Jews were offered a state on merely 4% of the full Mandate Palestine territory and they were willing to accept that. But al-Hussein rejected it out of hand. The Transjordanian leader at the time was the only Arab leader who had the sense to say ‘you have to accept this, otherwise Palestine will pass into Jewish hands whole. But al-Hussein could not take that into his anti-Zionism and his antisemitism – he could not fathom any sort of accommodation with the Jews.

So to explain that shift — in the beginning, it was driven by Arab self-interest. They were happy to get their 7 states. And the Jews get Palestine.

Emir Faisal wrote a hand-written amendment that his support of the Balfour Declaration for a Jewish state in Palestine is contingent on the Arabs getting their claIms met. But al-Hussein was so set in his anti-Zionism that he could never take that approach.

Q: People are generally aware of President Truman’s support for the establishment of Israel, but US support for a Jewish state goes back to Woodrow Wilson. What role did Wilson play?

Jewish leaders at the time were desperate for Wilson to make some sort of public statement to endorse the Balfour Declaration in 1918 just as the Paris Peace Conference was about to begin and a new path was dawning in the Middle East. He had Jewish acquaintances like Louis Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter and as a result of his own religious Christian background, he had a romantic view of the People of the Book returning to the land from whence they came.

But at the same time, there were forces pushing against that. There were Christian anti-semites urging him not to recognize Jewish national rights. The State Department was hostile to the idea of a Jewish state because of their desire to develop closer economic ties with the Arabs. So just as in the UK, Wilson also found himself torn between his own ideals and the forces trying to compel him against Zionism.

Then there were Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points, laying out the conditions for US engagement in WWI. They did not speak about the Jewish people, but they spoke about the autonomous development of the liberated lands of the Ottoman Empire. And that governing principle allowed the Jews to state their claim to what had become Palestine. There was the idea of the development of the native people of the Middle East – and the Jews were certainly one of those native people. And by extension, they had rights that should be recognized and were recognized.

And Wilson actually did make a statement in 1918, a very tepid statement that endorsed the Balfour Declaration, that he was happy that the work of the Balfour Declaration was being implemented, delighted to see the foundation be set for Hebrew University. That was a very important signal to the Jewish World about which side of the issue Woodrow Wilson stood. It was highly significant.

Then at the Paris Peace Conference, the US representatives were very clear in there support for the Balfour Declaration and for the establishment for the Jewish National claim to Palestine.

Wilson played an important role in developing an international consensus about Zionism right around that time.

7. The history of Modern Zionism offers a counterpoint to the perceived passivity of Jews during the Holocaust. How do we explain that in contrast to the heroism of Trumpador and the Jews of the Mule Corp who impressed British officers with their heroism in WWI?

There was a view, both inside and outside the Jewish world that the Jews were led like lambs to the slaughter. In some regards, there were episodes where one could say that the Jews did not cover themselves with glory, that they could have resisted more actively and aggressively. The natural capacity of Jews to resist Nazism, to save themselves, to fight back, was mostly non-existent. And I talk about Raul Hilberg the great Holocaust historian, who spoke about a formulaic response to danger that the Jews had honed over 2,000 years of exile.

Basically, their response was to alleviate their pain, to try to lobby governments, to write op-eds and to try to convince the public that the antisemites were wrong. Once the tide had turned against them, the Jews became wholly passive and submitted completely. But at the same time, we have to realize that the Jews had no real ability to defend themselves against a military power of overwhelming strength with the mission of destroying every last Jewish life, aided by collaborationist governments and police forces and populations in almost every place they entered. Jews were unarmed.

But after the Holocaust, you have the Jews in Palestine seeing what happened to their brethren in Europe and saying this is what can happen to Jews who are weak and vulnerable and unarmed – and we must never allow that to happen to us.

This leads to a sort of rehabilitation of the Jew.

There were events before which had a similar impact. The Holocaust, being on a larger scale, had a bigger impact. The Kishinev pogrom, almost a miniature version of the Holocaust, incited by clerics and policemen and government officials in a terrible massacre of Jews – was followed by stories coming out of rapes and murders, making the Jews feel a sense of vulnerability but also a sense of solidarity with their own people. This invigorated the Jewish people and was turned into a major humanitarian concern. Yet also a sense of shame that this is what Jews had been reduced to.

This created in Zionism a redemptive quality: saving the Jews not only physically, but also spiritually and culturally. If you look at Zionism today, it is about a sense of Jewish pride – not a grotesque chauvinistic pride but rather a simple pride about belonging to a very special remarkable people, of who we Jews really are, and being willing to stand up for that and assert your rights and not fall prostrate in front of your tormentors.

Q: When it comes to the influence of external forces on Zionism and Aliyah, people think of the Holocaust. But you note that the early writings about Zionism as a political movement largely originated in the Russian Empire. Why would Russia have this influence?

By the late 19th century because of progressive migrations as a result of expulsions from Spain and Great Britain, and pogroms in Germany – Jews were moving further and further east. You had shifting borders in that part of the world so that you had more Jews living within the Russian empire than anywhere else. Along with that, you had unsparing brutality generation to generation such as the Chelminsky pogroms.

People look at Israel being a reaction to the Holocaust, but there is a long history and a long continuum that made the Holocaust not only possible, but also inevitable. When people ask how the Holocaust could have happened, the seeds of it can be found in Russia hundreds of years earlier.

Because of the emphasis on the Holocaust we see the view, especially by anti-Zionist activists, the claim that Israel is a burden on the Arabs to atone for European guilt. To assuage the guilt of 6 million killed, a Jewish state is planted in the middle of the Arab world. As if Jews are European interlopers with no claim to the land.

We have Rashida Tlaib with the claim that it warms her heart how the Palestinian Arabs warmly welcomed the Jews of Europe as refugees from the Holocaust. This is a double falsehood because it also claims they welcomed Jews when in fact there were boycotts, violence and strikes at every turn.

The right to a national home in Israel is not only a legal right, but it has also been established in the decades before the Holocaust and it is an existential necessity for the Jewish people.

When we look today at the persecuted and abandoned people of the world, Kurds, Syrians and Uighurs – it shows us what it means to be stateless and manipulated by the self-interest of others.

People like Sarsour are anti-Zionists and in my view antisemites who claim that Zionism is creepy and racist dedicated to negative purposes. But there are a lot of people who see through this and see Zionism as an inspiration.

I’ve seen in my own work, from the Assyrian community in Australia, the Muslims in China, Kurdish leaders. They look at the story of the Jews who have survived through 2,000 years inquisition, pogroms and forced conversions, yet retaining their culture and sense of peoplehood and formed a national movement that is compelling and coherent and actually achieved the return of the Jewish people to their ancestral land.

A lot of these abandoned, persecuted, stateless people are trying to take inspiration from that and are trying to model their own national movements from it.

Q: Before Great Britain became a bitter opponent to Jewish immigration into then-Palestine and successfully cut down the size of the state, there was a time that Great Britain had a romanticized view of Zionism and wanted to help the establishment of a Jewish state. What was that based on?

It came from a number of sources. It came from the Christian beliefs of people like Balfour, Lloyd George and Churchill, that the Jews should have the right to return home. When you compare them to the Christian Zionists of today, you see that it is such a beautiful concept for them. This is not the concept of End of Days or The Second Coming, requiring that Jews be in the land. This is a more benign and beautiful idea, that the Jews are the People of the Book who gave the world Ethical Monotheism. Who gave the Christians their foundation of texts and beliefs. They believed that the Jews who had been harried and persecuted throughout the world should have a national home.

Yes, there are also the realpolitik considerations.

In the early 1900s, there was a concern about a large Jewish refugee problem. This was a unique solution to that.

Another consideration that cannot be discounted is the work of Chaim Weizmann. He was able to captivate and engage everyone. He was a dynamic, magnetic personality. As mentioned earlier, Lloyd George in his memoirs credits his discussions with Weizmann as leading to the Balfour Declaration. The truth of that is open to speculation, but it is clear that Weizmann rendered an extraordinary service to the British and they were grateful.

So it was a combination of the practical and the idealistic.

But what you then have over the next 3 decades, is the change in government, waning idealism and of course much more urgent critical considerations. There is the growing Arab violence in the Middle East and the threats from Arab leaders.

When Trump made the recommendation for the recognition of Jerusalem, we heard about the threat of the burning of the streets of the Middle East, which did not transpire. But those threats were there then – and they are there now.

And the other great factor that changed the calculations and caused the British to overcome their idealism was WWII. During the leadup to WWII, the Balfour Declaration (which came in 1917, at the end of WWI) had come to be seen as a distant relic of the past and irrelevant when the major new threat was Nazism. The concern for the British, and Chamberlain expressed it, was that if we have to offend one side – let it be the Jews. He said that because he wanted the Arabs to be potential allies in the coming European war, which would metastasize the Middle East as WWI had.

This was politics because the Balfour Declaration had been enshrined into international law. Great Britain had a legal duty to bring about a National Home for the Jews, as contained in the covenant of the League of Nations and the San Remo Conference. The Balfour Declaration was not empty words – it was a binding legal promise that had been made.

These were jettisoned because there were more pressing political and economic considerations entering into their calculations.

Oil was also a consideration. Chamberlain made comments about that as well, that the center of gravity of oil production had now shifted to the Middle East. These were very real considerations by Great Britain and the US. The State Department was cognizant of the fact the Middle East was becoming crucial in international affairs. You had the Suez Canal, which was an important gateway. The romanticism and idealism became a secondary consideration.

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 10 });