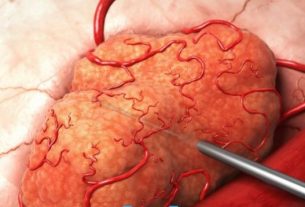

Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) is overseeing scores of projects. One of them, supported by both Israel and the Palestinians, is the €500 million Desalination Facility project for the Gaza Strip

by Neville Teller

Hope is flourishing in the Middle East. Many believe that the historic normalization deals between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain will broaden into increased cooperation across the whole region, leading to growing prosperity. If this is indeed a happy outcome, the groundwork is already laid. Certain well-structured organizations have been highly active, some for decades, sponsoring a multitude of humanitarian, financial, and developmental programs. The problem is that they have been operating under the radar, and that very little is known about them.

For example, how much is generally known about the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM)? Supported by a wide range of institutional partners, project promoters, international financial institutions, and the private sector, the UfM works proactively to achieve greater levels of integration and cooperation in the region. Believing strongly that security depends upon development since 2012 the UfM has sponsored no less than 59 regional cooperation projects with a budget of more than €5 billion.

The membership of the UfM consists of all 27 member states of the European Union together with 15 regional nations bordering the Mediterranean including Egypt, Turkey, Greece, Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian Authority (PA or, as it has designated itself, “the State of Palestine”). Libya has observer status, and Syria, once a member, has been suspended.

Euromed (the European Institute of the Mediterranean) is another rather shadowy body. Like the Ufm, it sprang from an EU initiative back in 1995 aimed at strengthening relations with the Arab nations of north-west Africa known as the Maghreb, and those bordering the western Mediterranean and its hinterland, known as the Mashriq. That EU-convened conference, held in Barcelona, aimed at encouraging cooperation between these nations, and in particular at constructing an economic and financial partnership between them and the EU leading eventually to a free trade area. The initiative came to be known as “the Barcelona Process”.

Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) flag

Despite the best of intentions, the Process failed to take flight. By its tenth anniversary in 2005, it had not come anywhere near advancing its program. The document it issued after its conference that year was not even endorsed by the partnership as a whole. The disagreement turned on what was to be understood by “terrorism”. The PA, Syria, and Algeria wanted to exclude what they called “resistance movements against foreign occupation”– “foreign occupation” being code for Israel’s existence anywhere in Mandate Palestine.

In the lackluster performance of the Barcelona Process, France’s then-president, Nicolas Sarkozy, perceived a political opportunity. He conceived the grandiose concept of a “Mediterranean Union”, paralleling the European Union. This project formed part of his manifesto during the French presidential election campaign in 2007.

Once elected, Sarkozy invited all heads of state and government of the Mediterranean region to a meeting in Paris, to lay the foundations. Unfortunately for him, his ambitious concept failed to inspire the EU. Some European leaders felt that it would not be sensible to duplicate institutions already in existence via the Barcelona Process. The European Commission thought that a better idea would be to use the existing Barcelona structure to build a more effective organization.

Sarkozy modified his proposal accordingly and obtained EU agreement for a project built upon the existing Barcelona Process. No longer a Mediterranean Union, but a Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), it would include all EU member states and be dedicated to supporting socio-economic developments in the region. Currently, it is overseeing scores of such projects spread right across the Mediterranean area. One such, supported by both Israel and the Palestinians, is the €500 million Desalination Facility project for the Gaza Strip, endorsed by all 42 member states of the UfM.

While no one could reasonably object to the encouragement of projects designed to bring improvements to the lives and living standards of the peoples of the Mediterranean, the exact relationship between Euromed and the UfM is somewhat puzzling. Both claim the Barcelona conference of 1995 for their foundation and the Barcelona Process as their inspiration, and both aim to achieve economic and developmental advances across the region. Their spheres of activity, however, are not clearly delineated. The Union, essentially project-driven, works by proactive involvement; Euromed describes itself as aiming “to promote economic integration and democratic reform across the EU’s neighbors to the south in North Africa and the Middle East”.

Then, in 2018 a third body emerged. Self-supporting and self-sufficient, PRIMA (Partnership for Research and Innovation in the Mediterranean Area) is the most ambitious joint program to be undertaken in the frame of Euro-Mediterranean cooperation. In the light of climate change, unsustainable agricultural practices, and over-exploitation of natural resources, it was set up specifically to develop more sustainable management of water and agro-food systems in the Mediterranean region. PRIMA currently consists of 19 participating countries including Israel but not the Palestinian Authority.

The main factor leading to the failure of the Barcelona Partnership – political instability – is as potent in 2020 as it was in 2005. What is new is the deal between Israel and the two Gulf states, and what it may lead to. An organization titled “The Union for the Mediterranean” might seem the expression of a far distant, possibly unattainable, vision – and yet there it is, active and flourishing, alongside its comrades Euromed and PRIMA.

A sensible way ahead? Amalgamation of the three existing bodies into one effective organization, rationalization of its operations, perhaps expansion of its activities beyond the Mediterranean region to embrace the Middle East as a whole, and – since public awareness of the existing bodies and their activities is minimal to the point of secrecy – better promotion of its purposes and achievements, for there is every reason for the good work to continue.

Neville Teller was born in London, read Modern History at Oxford University, and then had a varied career in marketing, general management, publishing, the Civil Service, and a national cancer charity. He began writing about the Middle East in the 1980s, and has published four books on the subject. He is the Middle East correspondent for the Eurasia Review, and writes regularly for various publications. He was made an MBE in 2006 “for services to broadcasting and to drama.”

Read more about: Israel-arab world, Middle East, Peace in the Middle East, Union for the Mediterranean (UfM)