If Daniel Schloff’s family had been on time to Yom Kippur morning services in 1965, he may have never encountered Sandy Koufax.

Schloff, who was 17 years old at the time and a senior in high school, lived around 45 minutes away from Temple of Aaron synagogue in St. Paul, Minnesota, the Conservative congregation his family attended. On Oct. 6, 1965, his father, who, he recalled, was “notorious for never being on time for anything,” was yet again running late.

By the time the Schloffs arrived for services, their typical seats in the seventh row were full. So the family found an empty spot near the back of the sanctuary. Schloff remembers noticing that two seats in front of them were empty, which was unusual given how packed the pews were on the High Holidays.

That quickly changed — in a way Schloff will never forget.

“We’re davening, and about 10 to 15 minutes in, two guys walk in and sit down,” Schloff recounted. “And as one of them sits, I get a profile, and that’s Sandy Koufax sitting right in front of me.”

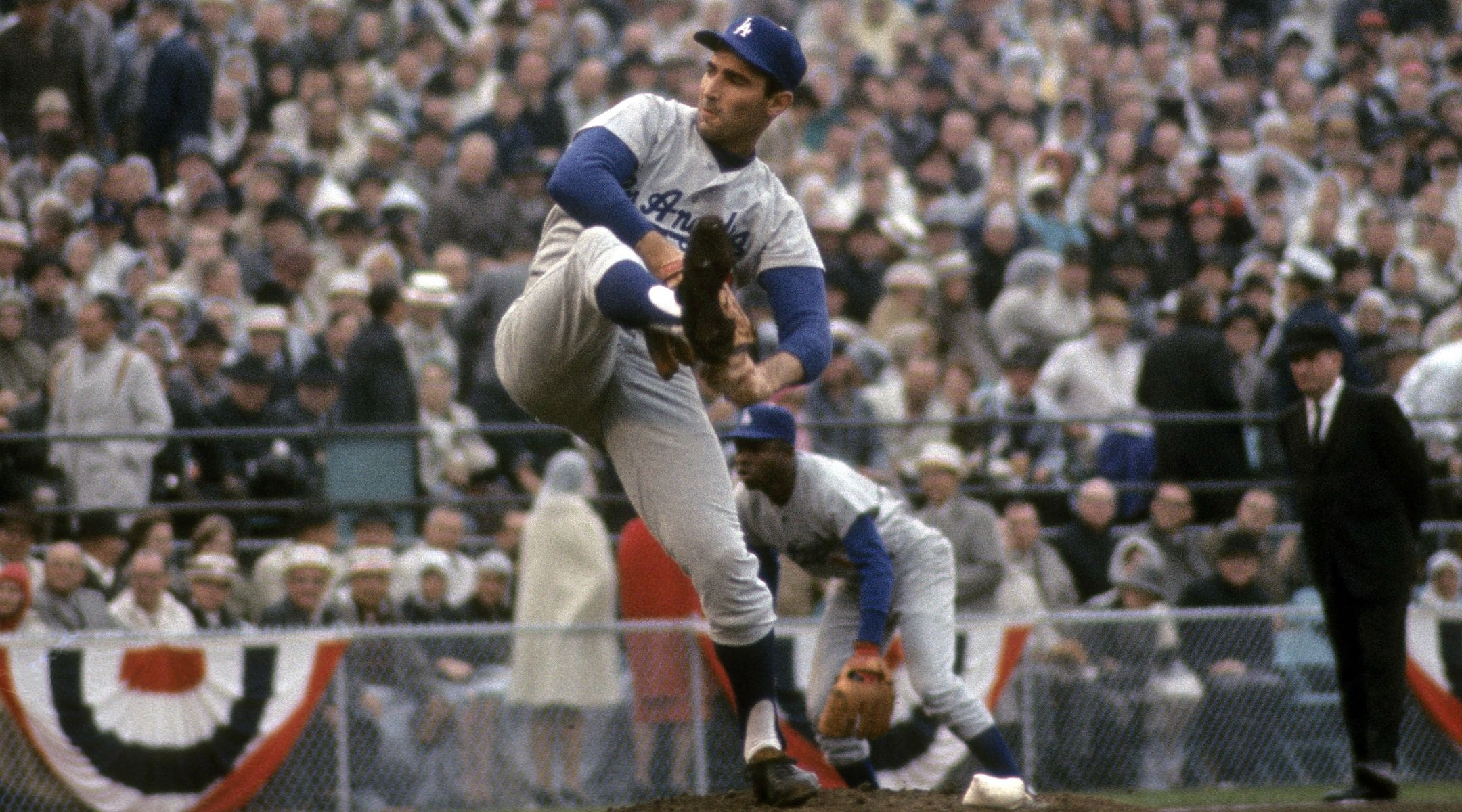

Schloff said he and the star pitcher nodded at each other and went about their prayers. Had it been another day, of course, Koufax would have been taking the mound as a star pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, who were in town to face the Minnesota Twins in the World Series.

Game 1 was that day, and Koufax, the best pitcher in baseball and possibly of all time, was slated to start — until he made perhaps the most famous decision of his career.

Not observant but proudly Jewish, Koufax decided he would not pitch on the holiday. It is a decision that 59 years later remains a defining moment in the history of American Judaism and an inspiration to future generations of Jewish athletes.

Over the intervening decades, multiple stories have been told about how Koufax spent that day, and whether he attended services. Koufax, who is famously private, has not confirmed or denied any of them.

Jeremy Fine, Temple of Aaron’s rabbi from 2012 to 2021 and a sports buff, wrote in 2020 that he had heard congregants insist they saw Koufax at services.

But the pitcher’s biographer, Jane Leavy, wrote that he spent the day in his hotel: “In fact, Koufax did not attend services there that day or anywhere else,” she wrote in “Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy.” But she indicated that her sourcing was second-hand, writing, “Friends say he chose to stay alone in his hotel room.”

Fine concluded that absent confirmation from the famously private Koufax himself, his whereabouts remain a “modern midrash,” or a Jewish story that has been passed down through the generations.

“It’s amazing that no one else — the most famous person in the world at that time, at that moment — no one else actually physically saw him,” Fine told (JR). “Unless Sandy says he was there, to me, it’s midrash. Midrash becomes folklore that’s a part of our story.”

To Schloff, there’s no doubt. He said he’s been “accosted on the internet” for retelling the story. But he insists he saw what he saw.

“He was there 100% and I sat behind him 100%,” said Schloff, who is now 76 and lives in Tucson, Arizona.

Schloff remembers Koufax, like the other adult men at services that morning, wearing a white kippah and a prayer shawl. Schloff said his fellow congregants observed the custom of being “Minnesota nice” and did not disturb Koufax.

“Everyone’s there for services, and the whole time I’m staring at the back of his bald head, davening, and thinking, huh, here’s Sandy Koufax,” said Schloff. “My God, here’s Sandy Koufax.”

That recollection — as well as Schloff’s description of Koufax as “a medium-sized, middle-aged Jewish guy, balding and dark hair” — casts a bit of doubt on whether the man he remembers was in fact Koufax. On one hand, Koufax was more than six feet tall, not yet 30, and did not appear to be bald. On the other hand, Schloff was a teenager at the time and was the same height as Koufax, so to him the pitcher may have in fact seemed to be older and not especially tall.

In any case, Schloff said he does not remember Koufax’s voice being “particularly on-key or off-key.”

“I was busy doing my Yom Kippur thing, and he was too. Nobody bothered him, which I thought was quite nice,” Schloff added.

Temple of Aaron in St. Paul. (Screenshot from Google Maps)

When services ended, Schloff said he got a head-on view of the future Hall of Famer. They wished each other a “Shana Tova,” Hebrew for a happy new year, and other congregants approached for a handshake.

Schloff’s account contradicts something else Fine wrote: that only two people in the synagogue ever testified that they had interacted with Koufax directly. But in addition to Schloff’s eyewitness account, there are other snippets of evidence that the famed pitcher did in fact attend services at Temple of Aaron that morning.

As Leavy writes in the book, the St. Paul Pioneer Press published a dispatch, headlined “Sandy Notes Holy Day,” on the morning of Game 1, that says the southpaw “planned to spend the night with friends in suburban Minneapolis, will attend services today and rejoin the team tonight for his starting assignment in Thursday’s second game of the world series [sic].”

But perhaps the most direct form of written evidence can be found in a Shemini Atzeret sermon that Temple of Aaron Rabbi Bernard Raskas delivered that year, which the synagogue shared with (JR).

“Last Thursday everybody in the Twin Cities watched the final World Series game,” Raskas said, according to the printed text. “Many of us had personal conflicts. The fact is that over and again people told me they wanted the Twins to win but they didn’t want Sandy Koufax to lose. No one had these mixed emotions except Jews.”

He continued, “But who among us would deny the fact that there was a secret pride in knowing that Koufax was a Jew who refused to pitch on Yom Kippur, who was in this very synagogue on Yom Kippur Day, and is now being proclaimed the greatest pitcher of our generation!”

Ken Agranoff, the longtime executive director at the synagogue, was also at services that morning. He was 12 years old at the time and said neither he nor anyone in his family laid eyes on Koufax. Still, he has reason to believe the tale may be true.

“If indeed he knew he could come here in a semi-secretive way and have a few hours of spirituality and/or prayer, great,” Agranoff, who’s now 71, told (JR). “That’s how I always have made the story make sense.”

Agranoff added: “I’ve worked in the Jewish world for now 37 years, and it’s amazing how we all adopt famous Jewish people and then we believe what we want to believe, and that’s my understanding of the story.”

Agranoff, who worked with Raskas and was a longtime friend of his, said the story has lived on at Temple of Aaron, where congregants sometimes speak of the tale around the High Holidays and the MLB playoffs, even as the ranks of those who may have been in attendance on Oct. 6, 1965, have dwindled.

Agranoff himself has attempted to confirm details of the story through his own investigation. Raskas, who died in 2010, once told Agranoff that the day before Yom Kippur, he had received a phone call asking if he could arrange a driver to pick up Koufax at his hotel and bring him to synagogue. Raskas never revealed any further details about the logistics.

If Koufax was indeed at Temple of Aaron, he was not necessarily in friendly territory. The Twins had not made it to the World Series since 1933, and the Dodger ace would have been surrounded by local fans who wore pins that said “Win Twins” in Hebrew. Years later, when the Twins did win the Fall Classic in 1987, Agranoff said the synagogue revived the slogan on a banner it displayed outside the building.

As Jews around the world gather for Yom Kippur services this weekend, Schloff emphasized that no doubt many will be reminded of Koufax and his defining act.

“I thought that it was excellent that someone with such an important task professionally to perform chose his Judaism versus that task that everybody, the whole world, was counting on,” Schloff said. “Literally, the whole world was counting on him pitching that game, and he didn’t. He chose to be a mensch.”

Agranoff said he once chased a lead on who he thought the pitcher’s driver was — but it was a dead end. Still, he said, he has no reason to believe that Raskas would fabricate the story — even if the rabbi was known as a bit of a “showman.”

“[Raskas] started hearing these stories also, and some people said, ‘Oh no, he never came. He never left his room. He never did this, never did that,’” Agranoff recalled.

“Rather than refuting or fighting about it, [Raskas] just had a bemused smile on his face,” he added. “He had a secret he wanted to keep, the aspect with regard to the logistics, and he said, ‘I have nothing that’s going to prove it, other than I arranged for the transportation. I know he was there.’”

Support the Jewish Telegraphic Agency

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, (JR) can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.