This article originally appeared on Alma.

At the turn of the 20th century, the city of Monastir, present-day Bitola in North Macedonia, was home to the country’s largest Jewish community, 11,000 people.

That’s about half of the current Jewish population of Turkey, most of whom share the Ladino language and its music with Balkan Jewish communities like Monastir. But in March 1943, Monastir’s Jews suffered genocide when the Nazis deported 98% of their people to Treblinka. None returned.

In 2017, Sephardic singer Sarah Aroeste received unexpected invitations from non-Jews in North Macedonia to perform her original Ladino songs in Bitola, the birthplace of her grandfather and her 104-year-old cousin Rachel Kornberg, who survived the Holocaust after being rescued by Albanian Muslims.

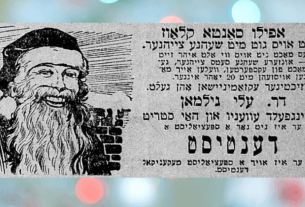

Kornberg family portrait, circa 1922 (Courtesy of Sarah Aroeste)

This experience inspired her new album, “Monastir,” which was released this week. Aroeste sings with Kornberg and Helena Susha, an 18-year-old opera singer from North Macedonia. With her Israeli producer Shai Bachar, she also collaborated with over 30 other musicians from Israel, Spain, Germany, North Macedonia and the United States.

The music revitalizes the lost Jewish presence in Monastir, an idea for which Aroeste found support both among the people of Bitola and the general population of North Macedonia. Non-Jewish North Macedonians were ebullient and nostalgic at the chance to celebrate the multicultural, interfaith fabric of their shared heritage with one of the community’s daughters.

“I was flabbergasted. They made all of the arrangements for me. That was the first hint that they really wanted me to come,” Aroeste says. “I arrived and I was immediately met with bouquets of flowers. I was whisked away. Press was everywhere, cameras, newspapers. And this was the very first time I set foot in Bitola.”

“Monastir” opens with the blowing of a shofar before Aroeste sings “Oy Qui Muevi Mezis” (Oh, What Nine Months), which is a “kantikas de parida,” or birth song in Ladino. It is an appropriate sounding of hope for the revitalization of Monastir’s Jewish community.

On half of the album’s 10 songs, Aroeste sang in Macedonian for the first time. She also studied how to pronounce the Monastir dialect of Ladino as part of the research for what became the largest production of her six albums to date, extending her range to perform new arrangements of traditional and original lyrics and compositions of Sephardic, Balkan and Flamenco fusions.

“When I returned to North Macedonia, it was to perform at a culture festival supported by the municipality of Bitola and the Israeli Foreign Ministry. It was a formal event. To prepare, a friend of mine suggested that I perform a Macedonian song,” Aroeste remembers. “‘Edno Vreme Si Bev Ergen’ [One Time I Was a Bachelor] struck me because it’s about a Slavic man wandering in the Jewish neighborhoods of Bitola. To me it’s humorous, but it also shows the interplay of cultures that existed prior to World War II.”

Aroeste consulted a wide scope of scholarly sources. One major inspiration was the National Authority of Ladino in Israel and the fieldwork of Max A. Luria, who in 1927 drew from a text dated to 1527 in Barcelona titled “Flor de enamorados.” It was preserved orally in Monastir for centuries until its music, like the community, disappeared. But inspired by the words, Aroeste wrote original music and called Israeli flamenco singer Yehuda “Shuki” Shveiky to perform it with her.

The song “Espinelo,” is a metaphor for Sephardic Jewry’s debt to Turkish hospitality when, during the Inquisition of 1492, the sultan welcomed them to settle in the Ottoman cities of Izmir, Istanbul and Thessaloniki. The chorus exaggerates the warmth of the Sublime Porte: ”The ladies watch over him, / The most elegant ladies of Turkey.” Shuki sings with the passion of a native Andalusian on the track, which tells a tale of Balkan Jewish superstition in which women who birthed twins were thought to have slept with two men. One ill-fated twin is thrown into the sea, only to be rescued by a fisherman and adopted by royalty. By historical interpretation, that empathic father king is Sultan Bayezid II embracing Spanish Jews after their exile east across the Mediterranean.

“In encased glass, I have my grandfather’s fez that he wore. He would always say that he was a Turk from Greece born in Monastir who spoke Espanyol (Ladino). It was as confusing to me then as it is now,” Aroeste says, laughing. “Interspersed on ‘Espinelo,’ we have Turkish qanun [a lap-style, plucked zither]. We wanted to infuse [the song] with the Ottoman Turkish sound to show that change from gritty Spanish flamenco to salvation in Turkey.”

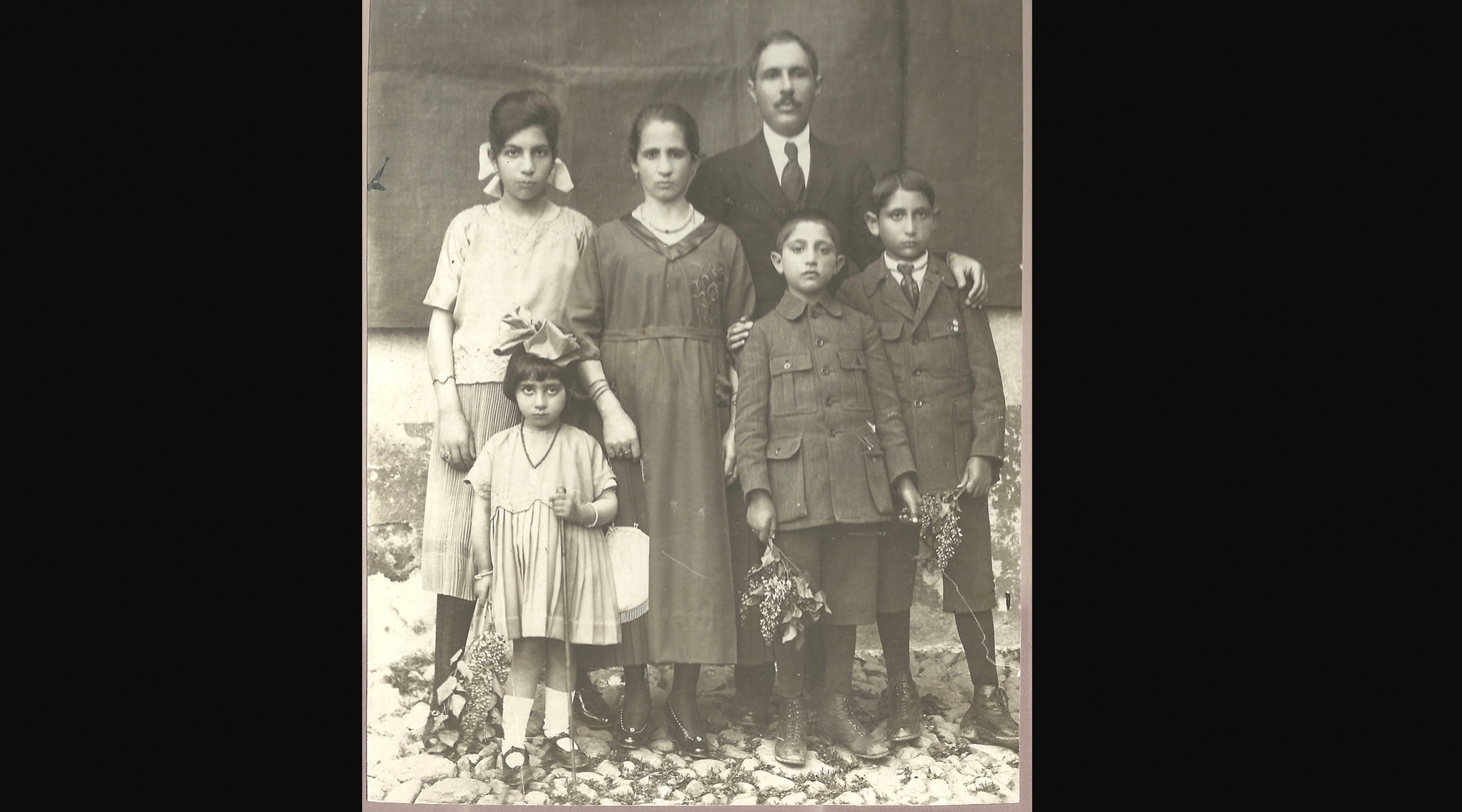

Sarah Aroeste’s grandfather as a child. (Courtesy of Aroeste)

The choice of flamenco for “Espinelo” is a nod to the innate fusions in Sephardic, Jewish and Balkan music. Their mixtures do not preclude their preservation; quite the opposite. The music of “Monastir” is rife with contemporary production details, from the didgeridoo that rumbles with shofar on the opening track to the children’s chorus on “Estreja Mara,” which immortalizes the living, present-day tradition of a Bitola kindergarten.

The centenarian voice of Kornberg introduces the upbeat song “Estreja Mara” by explaining the Ladino rhyme scheme of a Sephardic finger-game to Aroeste’s infant daughter. Then the chorus of children sings an anthem dedicated to a 21-year-old Jewish resistance fighter, Estreja Mara, who died in battle while standing up to the Bulgarian army in 1944.

Like Aroeste’s earlier albums, “Monastir” focuses on the importance of youth in revitalizing culture. She presents glimpses of life when young Jewish women and Slavic men mingled. “Edno Vreme Si Bev Ergen” features the Macedonian crooner Sefedin Barjamov, who accompanies Aroeste to adapt a tune most often heard via a 1978 recording by the all-male Biljana Ohrid Ensemble. The fact that Macedonian singers have never stopped reminiscing about Jewish neighborhoods in Bitola is a testament, in song, to the affection and even love that North Macedonian people of all backgrounds have for the memory of their destroyed, local communities.

A family walks the streets of Bitola. (Courtesy of Sarah Aroeste)

“Monastir” is more than a resonant echo. It is a strong response to genocide, harnessing the power of Sephardic music to revitalize Jewish culture and celebrate its often unsung endurance in the midst of linguistic endangerment. Aroeste plans to perform internationally with her illustrious cast of guest musicians. She is confident that her album will support historic initiatives like the restoration of Monastir’s Jewish cemetery.

“So many revitalization efforts look back at traditional repertoire … Music from a hundred years ago can still be newly recorded,” she says. “Ethnomusicologists are doing incredible work.

“However, people are not going to learn about Ladino and this culture unless we make it accessible and find ways to reach them. I firmly believe that to keep Ladino going, to expose it to more people, we need to be creating new material. There are a lot of ways we can do this. The music of Monastir had never been compiled in one source. There’s still an uncovered treasure trove of material.”