(JTA) — We are in an era of multiple interlocking crises. From record-breaking heat waves to wildfires to water shortages, from rising authoritarianism to a pandemic rampaging across the world, it is clear that, to survive, human beings will need to make urgent, major changes to how we live.

Bold policy proposals already exist to address these problems, both nationally and in different states. Additionally, we — one of us a politician, the other a rabbi, and both progressives — want to suggest another possibility, gleaned from Jewish tradition: the ancient idea of shmita, the sabbatical year, which can guide our work in this urgent moment when everything we do matters.

Both of us are millennials, and therefore have come of age under the worst inequality since the Gilded Age — exacerbated and symbolized by a student and healthcare debt crisis. The disastrous effects of climate crisis, extinctions, displacement and environmental degradation are threatening to turn life into a nightmare for most on the planet. These problems can be traced to a global obsession with unending growth.

Our only chance to avoid that is to drastically re-envision our society and its priorities.

Both of us are also, in particular, Jewish millennials. We have, in different ways and at different points in our lives, felt called to participate in Jewish communities of learning, prayer and communal gathering. Despite our involvement in those spaces however, neither one of us learned of shmita’s existence until adulthood. It is time for our Jewish spaces, around the world, to re-prioritize this sacred ritual, and apply its wisdom in concrete ways to our own times.

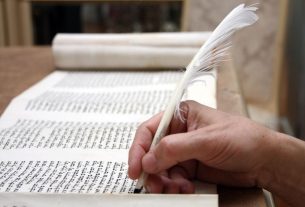

The word “shmita” is observed every seven years. The shmita year began several days ago, on Rosh Hashanah. “Sabbatical” tends to refer to respite from work, typically in a university context. But the shmita year is slightly different. It is a collective sabbatical, a radical recalibration of society as a whole, in order to align it with principles of justice and equity for human beings and for the lands we inhabit. Shmita offers a framework for how we might enshrine seemingly individual choices as social values.

The shmita year has two major components. The first is that it serves as a rest for land: Just as humans get to observe a sabbath once every seven days, the land that we inhabit gets a sabbath, too. In biblical times, it meant that the land should lay fallow for a year, and the gleanings left for the needy and even animals. Through shmita, our relationship to land can shift from one of control and domination to one of appreciation and interdependence. Clearly, such lessons are applicable to this moment as well.

Shmita’s other major component is that debts are forgiven. This is done to address financial inequities that grow over time, and to enable everyone to have the opportunity to thrive. Debt forgiveness every seven years disrupts wealth-hoarding, and provides relief to those struggling to meet their basic needs. Shmita approaches justice expansively.

These ideas can be, and should be, used in practice — not just in our ancient texts, and not just aspirationally. For instance: we could forgive debts, and change the systems that cause such terrible indebtedness. Two-thirds of contemporary U.S. bankruptcies are over medical issues and medical debt; we must make healthcare free and universal to solve this problem over the long term. Collectively, U.S. college students owe nearly $1.6 trillion in student loan debt; President Biden could and should forgive up to $50,000 per borrower in federal student debt through executive action. Over the medium term, we must make public colleges and universities free, to avoid re-creating the same problem — something that our home state of Rhode Island is already on its way to doing. This year, its General Assembly permanently enacted RI Promise, the free tuition program at the Community College of Rhode Island.

The idea of shmita can also guide us in acting to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change. Shmita proposes that for a year, humans must avoid treating land simply as a means to our ends; we must not think in terms of limitless expansion, but rather in terms of sustainability and rest. Leaving the land fallow rejects the notion that our planet, and its resources, exist only to serve us.

Our state’s Act on Climate bill sets legally binding targets for emissions reductions; now we must act urgently to meet them. Measures like mandating net-zero emissions in energy generation, a critical move that passed only the Senate this session, are crucial first steps. We need to rebuild our food systems, and expand public transit and clean energy production. Neighborhoods are building community gardens while offering training for formerly incarcerated people, rethinking financial systems, and experimenting with basic income. Communities and legislatures are mobilizing around these issues, but we need more action, faster, and at every level.

The choices we make now will determine the survival of millions within the next few decades. We must seek out every strategy available to us as we take on the challenges that threaten the inhabitants of our country, other countries, and our planet. That includes strategies anchored in ancient wisdom, like the shmita year. We need to act collectively, for everyone’s health. Because a society that takes care of itself and its most vulnerable is one that is, quite simply, the only moral option.