Israel has returned relatively quickly to the familiar situation before the COVID-19 pandemic, characterized by a low rate of public expenditure on healthcare. However, it needs to adjust to the post-crisis reality – the war against Hamas – while continuing to plan for the long term to deal optimally with challenges. So say researchers at Jerusalem’s Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in the chapter on healthcare in its 2023 State of the Nation Report.

The chapter, written by Taub researchers Prof. Nadav Davidovitch (who is also dean of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev’s School of Public Health), Natan Lev, and Dr. Baruch Levi, presents a status report on the healthcare system in Israel before the war and shows some of the challenges and problems facing the system, as well as efforts to cope with these issues.

On the one hand, the chronic shortage in the healthcare workforce is worsening, and the number of hospital beds per population continues to be low. On the other hand, there is a marked decline in infant mortality and a rise in the number of new licenses issued in the healthcare field.

Israel’s healthcare system

Israel gets poor marks for being ranked in the lower third of the OECD countries in national healthcare expenditure. In 2022, the national expenditure on healthcare at current prices was NIS 132.6 billion. In fixed terms, this is an increase of 0.8% relative to 2021, although per-capita expenditure decreased by 1.1%. The expenditure in 2022 was 7.3% of GDP, as compared to the OECD average of 9.3% and the US expenditure of 16.6%. This figure puts Israel in the bottom third of the OECD countries. Israel also ranks low in terms of public expenditure on healthcare out of national expenditure, with only Portugal, South Korea, and Chile ranking lower.

Regarding sources of financing, in 2022 about 23% of national expenditure on healthcare was financed by a health tax and another 42% was financed from the state budget. Total private financing accounted for about 34%, of which almost one-quarter were direct payments by households for medications and medical services.

The number of new medical licenses is rising, as well as certification in healthcare professions; the number of nurses is also increasing following a prolonged downward trend since the 1990s.

The per-capita rate of physicians in Israel is lower than the OECD average, although in the past decade, it has risen slightly from 3 to 3.3 physicians per 1,000 population and is nearing its level in 2000.

The rate of graduates from foreign medical schools is higher in Israel than in any other OECD country at close to 60%. Nonetheless, there has been a decline in their number over the past decade, primarily following the Yatziv Reform that reduced the list of foreign medical schools that are recognized in Israel.

In 2021, 2,024 new medical licenses were issued, which is 2.8 times the number issued in 2010. Of these, 776 were issued to graduates of Israeli medical schools, which is 2.2 times the number issued in 2010. However, this increase, they wrote, is insufficient. In 2025, the number of students ready to start internships is expected to drop by 30%, and together with the growth in the population and needs alongside the aging of medical staff, the crisis in the medical workforce in the healthcare system is likely to become even more severe.

The researchers stressed that, in the past few years, the Health Ministry has invested a good deal of effort in attempts to solve – or at least minimize – the workforce crisis.

The number of hospital beds in Israel is significantly lower than the OECD average, particularly in the periphery. The ministry has produced a plan that officials say will improve the situation.

In 2022, the rate of general hospital beds in Israel (excluding psychiatric hospitalization beds) was 1.77 per 1,000 population, which is slightly higher than in 2021, when it was 1.75. Although the number of beds has been on an upward trend over the years, it has declined in per-capita terms. This trend is in line with international trends and the move towards community care rather than hospitalization; nevertheless, the number of hospital beds in Israel is still significantly lower than the OECD average (3.4 per 1,000 population in 2021).

The low number of general hospital beds is especially pronounced in the periphery; in Tel Aviv and the Haifa districts, the number of per-capita beds is the highest, while in the North and South, they are the lowest.

According to the plan recently presented by the ministry, the number of beds is expected to grow by about 11% in coming years, but given the rate of population growth and the aging of the population, the per-capita rate in Israel will remain lower than in the OECD countries.

Apart from the low number of general hospital beds, there is also an unequal geographical distribution – with the per-capita number of beds highest in Tel Aviv and Haifa, while it is lowest in the South.

On December 27, 2023, the Health Ministry published its plan to expand hospital beds in the coming years, including an additional 1,790 general hospitalization beds, 300 rehabilitation beds, and 245 beds for psychiatric hospitalization. This plan has been modified to meet the needs of the war, with an emphasis on mental health and rehabilitation needs.

In 2028, with the completion of the plan’s implementation, the number of beds per 1,000 population will be 1.77.

As for the health status of the Israeli population, life expectancy is still higher for women than for men; the mortality rate is high in Yeroham and Dimona; and there has been a substantial decline in infant mortality.

Life expectancy at birth is high in Israel relative to the OECD countries, and according to 2022 data, Israel is ranked seventh in the OECD, with an average life expectancy of 82.9 years. Rates for 2023 are expected to continue to rise, with the slowing down of the COVID-19 virus. The research shows that life expectancy for women is higher than for men – 84.9 years versus 80.9 years.

There are also disparities in life expectancy among population groups – the life expectancy of Arab men is the lowest, while that of Jewish women is the highest. Education also affects life expectancy: the gap benefiting individuals with post-secondary or academic education is 6.2 years for women and 6.1 years for men.

There are also large disparities in mortality across districts and population groups. The highest death rates have been seen primarily in places with a low socioeconomic level and the periphery. In a breakdown by population group, high mortality rates were found primarily in Arab localities, although also in Yeroham and Dimona. By contrast, low rates of mortality were found in a diversity of cities, most of which are located in the center.

Another measure of health characterized by disparities is infant mortality. In general, Israel has a low infant mortality rate relative to the OECD countries. Over the years, there has been a significant decline in infant mortality in both the Arab and Jewish sectors, but there is still a substantial disparity between the two sectors. In 2020, there were 1.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in the Jewish sector as opposed to 4.7 in the Arab sector. There are also disparities on a geographical basis – the rate of infant mortality is highest in the southern region, in particular among the Arab population, while the lowest rates are to be found in the center and Tel Aviv.

Individuals postpone or avoid consulting their doctors due to long waiting times, they found. An examination by the Taub researchers of waiting times for medical consultation services shows that, on average, they range from 31 to 83 days. Similarly, large disparities were also seen by region, demographics, and health status. The longest waiting times were reported in the center, Tel Aviv, and the South, while the shortest were reported in the North. Jews and others reported longer waiting times than Arabs, while the chronically ill, who consume more medical consultation services than the rest of the population, wait longer than individuals who are generally in good health.

The study reveals that long waiting times are the main reason that people refrain from getting medical treatment – 35% choose not to get medical treatment for this reason. Other reasons are distance (19%) and cost (12%).

An examination of the expenditure of the health funds on complementary healthcare services (Shaban) from 2019 to 2020 shows very large gaps between their expenditure on Jewish and non-Jewish populations. The Jewish population is characterized by a high proportion of members who buy complementary insurance. In 2020, at least 76% of the Jewish population held complementary insurance, while only 46% of the non-Jewish population did.

The health funds also spent more on complementary insurance for the population in Jewish cities. From 2019 to 2020, the cost per beneficiary in complementary insurance was 2.3 times higher in a Jewish city than in a non-Jewish one.

The disparity in average annual medical expenditure per beneficiary between Jewish and other cities ranged from NIS 257 to NIS 361. Similarly, it appears that there are more complementary insurance beneficiaries outside the periphery, and the disparities are especially pronounced in Leumit Healthcare Services and Meuhedet Healthcare Services.

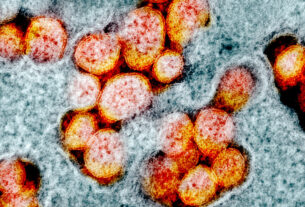

The authors reported that new strains of COVID-19 are more infectious, but vaccinations are still effective. Following a continuous decline in the number of serious cases of the coronavirus since the beginning of the year, their number has grown about three-fold since last June. There has been a notable increase of new and more infectious variants in other countries, including the US. Nonetheless, they are similar in their clinical severity to the previous Omicron strains.

The highest rate of hospitalization due to COVID-19 is found among the 60+ age group, with a peak in the 80+ age group. The data on seriously ill patients and the number of deaths paint a similar picture, with a peak in the 80 to 89 age group. An examination according to vaccination status shows the highest mortality among the non-vaccinated, which appears to indicate that the vaccination is still effective in preventing severe morbidity and death.