Photographs and postcards. A children’s calendar, filled with games, poems and stories. A partially darned sock, remnants of a project that was never finished.

Such workaday items can be found inside just about any apartment in New York City. But the ones on display at the Center for Jewish History near Union Square are special — because they come from the cramped attic apartment in Amsterdam where Anne Frank, her family, and another four Jews famously hid from the Nazis for two years before being discovered and deported to concentration camps, where seven of the annex’s eight inhabitants perished.

The display is part of the first-ever full-scale replica of Frank’s annex — one that aims to introduce new audiences to the most famous victim of the Holocaust at a time when anxiety is high over whether its lessons have been learned.

“What we have tried to do here is not a complete imitation of what is in Amsterdam,” said Ronald Leopold, director of the Anne Frank House, which is a major tourist destination in Amsterdam. “We’ve brought many artifacts here which are rarely, if ever, on view in Amsterdam. What we tried to do is actually touching people’s eyes in presenting Anne’s life story.”

“Anne Frank: The Exhibition” opens on Monday — Jan. 27, International Holocaust Remembrance day, which this year commemorates the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz — and recreates, in painstaking detail, what life was like for the eight Jewish residents of the attic apartment known as the secret annex, down to minute details like peeling wallpaper and the photos tacked to the walls.

The exhibition also includes more than 100 original artifacts related to the Frank family, many of which have never before been shown publicly. These include a Dutch version of Monopoly — a game Anne Frank loved, which she had played with a classmate at Amsterdam’s Jewish Lyceum. They also include a 1947 letter from a New York publisher to her father, Otto Frank, declining to publish the soon-to-be world-famous diary of his murdered daughter.

Among the treasures on view is a Dutch version of Monopoly that Anne loved to play with a classmate from Amsterdam’s Jewish Lyceum. (Ray van der Bas)

Annelies Marie Frank was born in Frankfurt, Germany in 1929, the youngest of two daughters born to Edith and Otto Frank. The family moved to Amsterdam in 1934, after Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany, and in 1942 the Franks, along with their friends the van Pels (and later, another friend, Fritz Pfeffer) went into hiding in the small, three-story apartment above Otto Frank’s office.

Anne Frank received her diary as a 13th birthday gift; in its pages, she chronicled everything from the restrictions placed upon Dutch Jews and descriptions of life in the annex to her contempt for her mother, her briefly budding romance with Peter van Pels, and her future aspirations to become a journalist.

After being deported, Anne and her sister Margot died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen, a Nazi concentration camp, just months before the end of the war. Of the eight Jews who hid in the annex, only Otto Frank survived.

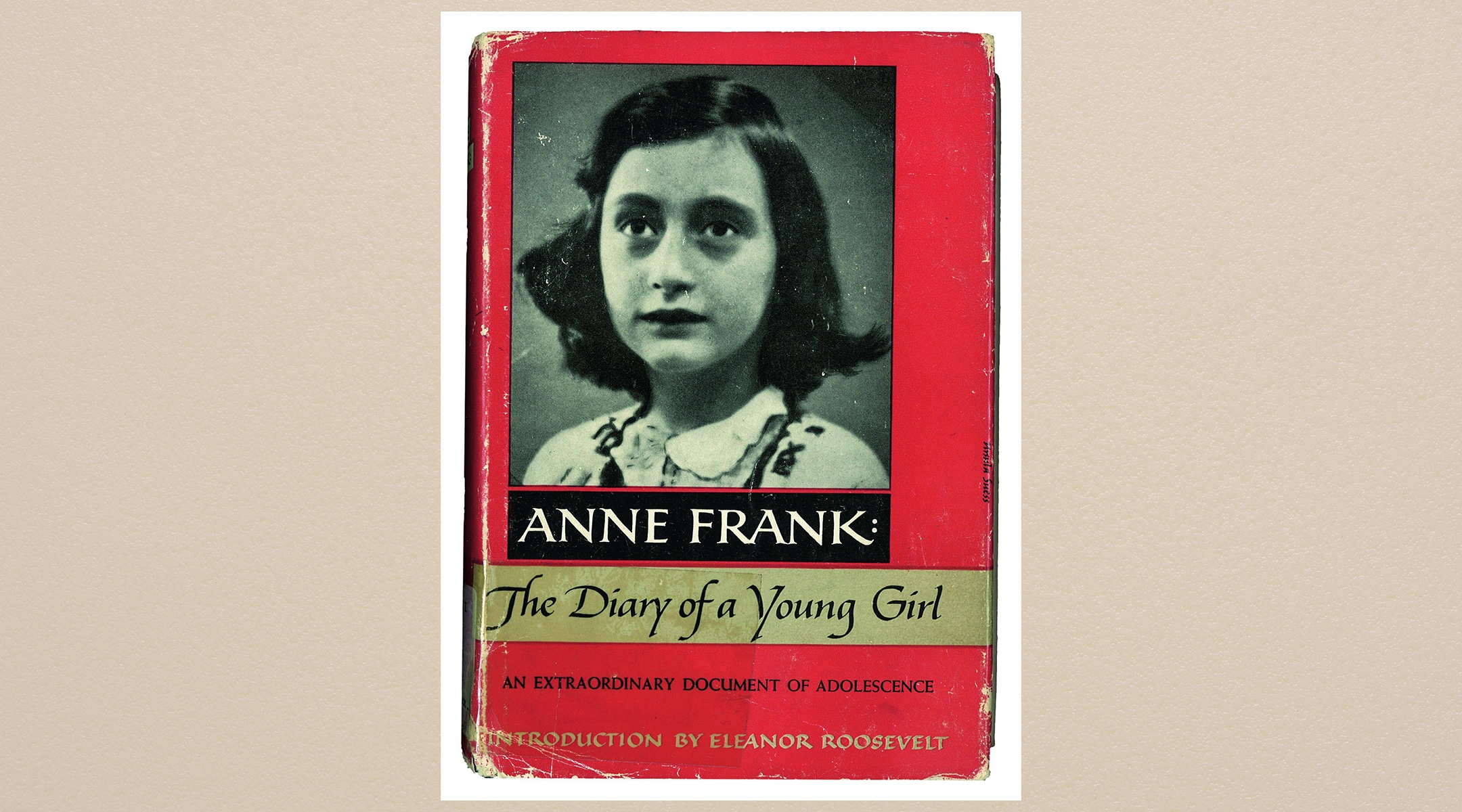

Miep Gies, who had helped those hiding in the annex, had preserved Anne’s writings and shared them with him; a Dutch publisher released a version of the diary in 1947. Known in English as “Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl” the diary has been translated into more than 70 languages, and the book is seen as an essential tool of Holocaust education.

“Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl” has been translated into more than 70 languages; pictured here is the first American edition. (Harold Strak)

As Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in a dispatch of her column, “My Day,” ahead of the book’s U.S. publication in 1952: “This diary should teach us all the wisdom of preventing any kind of totalitarianism that could lead to oppression and suffering of this kind.”

The traveling exhibition is designed to bring Anne Frank’s story to those not able or inclined to travel to Europe, or who might not even know her story. And it also offers an opportunity to do something that Otto Frank expressly prohibited in Amsterdam — fill the space. His vision was to force visitors to reckon with the emptiness created by the murder of 75% of Dutch Jews.

“Absence is a key element in the concept of the Anne Frank House,” Leopold said of the Dutch institution, which draws more than 1 million visitors annually. “So if you bring Anne’s story elsewhere, you need to make adjustments in the concept.”

The exhibit arrives in New York at a time of alarm about antisemitism locally and around the world. Its curators say that seeing relics of Frank’s life could ignite investment in her story.

“Empathy is a wonderful starting point for education and encouraging them to not just reflect on why it happened, but also to respond to it in their own communities,” Leopold said.

“We know that antisemitism will never totally disappear,” he added. “We need to keep it under certain levels. And I think that’s our challenge, and it will continue to be our challenge. We need to keep working on that, and I think this exhibition is very much contributing to that.”

In addition to the 7,500-square-foot multimedia exhibit, which was created by the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam in collaboration with the Center for Jewish History, the project includes an educational curriculum for student visitors, created in partnership with The Anne Frank Center at the University of South Carolina.

In the New York City exhibit, Anne’s story is told chronologically, beginning with her early life and childhood in Germany, through the rise of the Nazi party, the family’s flight to Amsterdam and ultimately, into hiding, through Otto Frank’s postwar life and the publication of Anne’s diary.

The exhibit uses photographs, videos and voice recordings, though perhaps among the most arresting elements is a map of Europe, glowing beneath a glass floor, that depicts the locations of every concentration camp and sites of mass killings during the Holocaust.

“Anne Frank: The Exhibition” also includes a recreation of the kitchen inside the annex. (John Halpern)

“We all know that the diary is about the two years in hiding,” Tom Brink, the exhibition’s curator, told the New York Times. “But of course, the story is much bigger than that. It starts earlier, it ends later, and that entire story and entire journey deserves to be told.”

The exhibit’s organizers hope to reach at least 250,000 students and is subsidizing access for visitors from New York City public schools and other public schools with many students from low-income families. (Otherwise, tickets cost $21 during the week and $27 on Sundays.) Tens of thousands of tickets have already been sold for the exhibit, which runs through April 30 before going on tour across the United States.

“It’s important to recognize that the interest among young generations in the story of Anne Frank is rather increasing in the United States,” Leopold said. “So we see, still, a huge interest in the story of Anne. In visiting the [real] house, we cannot accommodate all the people that would like to visit this place.”

“Anne Frank: The Exhibition” will be on view at the Center for Jewish History (15 West 16th St.) from Jan. 27 through April 30. For tickets and more information, click here.

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.