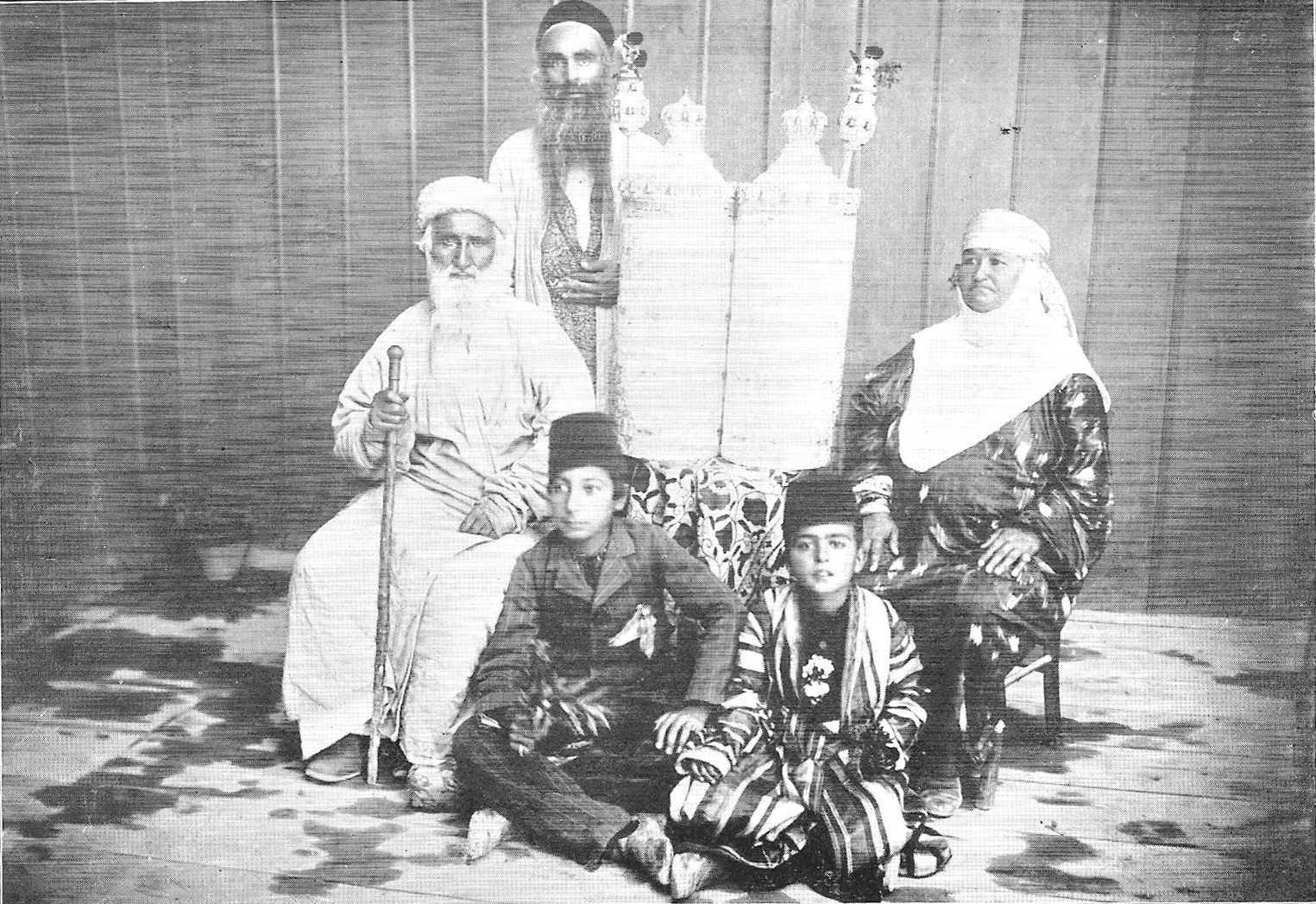

At the far edges of the Jewish world, Bukharan Jews (also sometimes referred to as Bukharian or Bokharan Jews) have made their homes in Central Asia’s vibrant cities — now located in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan — for well over a millenia. One of the world’s oldest diaspora groups, they came to resemble the Muslim Tajiks and Uzbeks amongst whom they lived, all the while maintaining connections to the wider Jewish world.

History

Folk tales suggest that ancestors of Bukharan Jews were among the Lost Tribes who arrived in this region after the Assyrian exile in 722 BCE. Most historians, however, agree that the first to arrive were among those exiled from the Land of Israel at the hands of the Babylonians in 586 BCE.

In the twelfth century, renowned Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela recorded that 50,000 Jews lived in Samarkand, among them “wise and very rich men.” Although these numbers are widely believed to be exaggerated, the data indicate that the city was home to a robust and well-established community at the time. Throughout the Middle Ages, the fate of the region’s Jews oscillated. During periods of persecution and instability, Persian-speaking Jews moved between the various territories today demarcated by Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, seeking shelter among one another’s communities.

In the latter half of the 19th century, much of Central Asia came under Tsarist Russian colonial control. Though Tsarist rule was largely oppressive for the Jews of eastern Europe, it was favorable to Central Asia’s Bukharan Jews.

Taking advantage of economic opportunities provided by the telegraph and railroad, and new trading rights extended to Jews in the region, a wealthy, well-traveled Bukharan Jewish merchant class emerged. Their travels and business took them as far east as China, and west to France and England. In addition, pilgrimage to Jerusalem became popular. In 1890 a Bukharan Jewish residential quarter was established in the city, renowned for its wide tree-lined avenues and its majestic architecture, a blend of Central Asian and Western European style.

In 1924, in the wake of the Russian Revolution, the Soviets redrew Central Asia’s boundaries, creating the republics of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, which ultimately became independent states in 1991. These two republics had been home to some 50,000 Bukharan Jews, who considered themselves indigenous to the region, having arrived before Islam was introduced to the area, and before the Uzbek dynasts conquered the territory. Yet, their deep roots were not strong enough to withstand the changes that swept through the region with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the rise of independent nation states. Mass migration –– primarily to the United States and Israel –– began on the eve of the dissolution of the USSR. By 2015 only a few hundred remained in Uzbekistan and far fewer in Tajikistan.

Language

Prior to the late nineteenth century, Bukharan Jews’ primary spoken language was a Judeo variant of the local Persian. The group’s literary tradition, shared with the Jews of Iran and Afghanistan, included Persian texts written in Hebrew script, which narrated biblical chapters (such as the story of Purim and Hanukkah, the conquest of Joshua, and the life of Moses) in verse form. In the early twentieth century, a printing press and new cultural projects emanating from the Bukharan Jewish quarter of Jerusalem gave rise to a literary renaissance, with religious scholar and linguist Shimon Hakaham at its helm. In Uzbekistan, meanwhile, language projects sponsored by the early Soviet regime resulted in the printing of Bukharan Jewish language textbooks for school children, newspapers, poetry, as well as the rise of a theater.

By 1940, however, the promotion of an independent Bukharan Jewish language was banned. Throughout the Soviet period, Bukharan Jews in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan studied Russian in school. Today, many are trilingual, speaking Russian, their native language (often referred to today as Bukharian) and Hebrew, English or German (depending on where they currently live).

Relationship with Wider Jewish World

Living on the silk-route, Central Asia’s Bukharan Jews oscillated between periods of contact with the wider Jewish world and periods when their political situation prevented travel and trade. Contradictory reports about the late-eighteenth century traveler Yosef Maman illustrates this paradoxical situation. Maman, a Sephardic kabbalist is said to have stumbled upon the Jews of Bukhara in the late 18th century. In one version of the story, he found them to be ignorant of basic Jewish religious tenets and practices, and remained in Bukhara to teach and reconnect them with the wider Jewish world. Recent scholarship, however, challenges this version of history, portraying it as a legend intended to delegitimize Bukharan Jews’ local traditions. By contrast, Bukharan Jewish historians depict Maman’s arrival as part of a long-standing flow of Jewish traffic between east and west.

The Tsarist period is remembered as a Golden Era for Central Asia’s Bukharan Jews. The rise of a well-traveled nouveau riche mercantile class allowed for Bukharan Jews to build a residential quarter in Jerusalem, and contribute to other charitable causes in Ottoman Palestine/pre-State Israel, including hospitals, orphanages and burial societies. During this period, Central Asian rabbis were brought into far-reaching conversations with rabbis in Ottoman Palestine regarding issues including kosher meat slaughtering and laws of marriage and divorce. Prayer books, Passover haggadot, and handbooks of Jewish practice, which were published in Jerusalem, circulated back to the Jewish communities in Central Asia.

In the 1920s, the Soviets dismantled the Bukharan Emirate, cut through old borders, carved new ones and incorporated the region into the USSR to create the Soviet Social Republics of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Under Soviet rule, mobility and communication was highly restricted, bringing an end to Jewish participation in international social, religious and trade networks. Still, they maintained some contact with other areas of the Jewish world through relatives who had immigrated in previous years, and through Jewish travelers who trickled into the area throughout the Soviet period. Finally, Bukharan Jews encountered Jews who fled or were evacuated out of Central Asia during World War II. Of note is their contact with Lubavitch Jewish refugees, who had a significant impact on Jewish practice, particularly in Samarkand.

Once the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, representatives from Jewish organizations in the United States and Israel traveled to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to work with the local Jewish communities. Chabad, the Jewish Agency for Israel, B’nai Akiva, the Joint Distribution Committee and Midrash Sepharadi offered aid, provided kosher food, taught Jewish classes, ran summer camps and engaged youth in Jewish cultural and social programs.

Mass Migration: Causes

Bukharan Jews left Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in very large numbers when the borders reopened in 1989 and the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Locals suffered instability due to economic chaos and weaknesses in the changing state welfare systems, including social security and health insurance. As an ethnic minority, most of whom were not highly proficient in the Uzbek language, Jews were also largely excluded from the project of nation building; they were not admitted to universities, and many were let go from their state-sponsored places of employment. As non-Muslims, Jews were further marked and stigmatized as outsiders. In neighboring Tajikistan, which was experiencing a long-standing civil war, the situation of Bukharan Jews was even more precarious. By 1993, approximately half of the region’s 50,000 Jews had left; most for Israel or the United States, and some for Austria, Germany and Canada.

Conditions stabilized in the second half of the 1990s, and Jewish life was enriched through the establishment of branches of international Jewish organizations (such as Chabad, the Joint Distribution Committee and Midrash Sepharadi). Nevertheless, migration continued as individuals followed their siblings, children and in-laws who had already left post-Soviet Central Asia. By the close of the 20th century, one of the longest chapters of Jewish diaspora history had come to an end.

Cultural Practices

Cuisine infused with local spices, colorful embroidered caftans with golden-tassel caps, and a rich musical tradition inflected with Central Asian sounds are all hallmarks of Bukharan Jews’ rich cultural life. Also noteworthy are their distinct religious practices, which show how the group adapted to the Turko-Persian Muslim and Soviet environments in which they lived.

Far from the seat of Soviet power, most also continued to keep kosher and celebrate major Jewish holidays and life-cycle rituals. These rites, however, were mostly held in secret and conducted without prayer books or other religious guidebooks, which were banned under Soviet rule. Due to going underground, their Jewish practices took on features that further distinguished them from Jews in other parts of the world. Weddings, for example, were broken into two distinct components. The civil ceremony, conducted at the state-governed “Palace of Culture” was followed by large celebrations with music and feasting. The religious ceremony, by contrast, was held late at night, with only the closest family members present. The few guests permitted to attend were expected to raise their hands above their heads and open their fingers wide throughout the ceremony to signify that they were not hiding anything or harboring any ill-will.

Bukharan Jewish rites of mourning held during the seven-day period after burial (shiva) are carried out much the same way as they are among Jews around the world. However, the local custom of yushvo —a special multi-course meal of symbolic foods interspersed with eulogies, songs of mourning and prayers — is added to these practices. The ceremony is held every evening during the week of shiva and for the next month weekly on the day that the person passed away (for example, every Wednesday). Further, during the entire first year of mourning, a yushvo is held each month on the date that the person had passed away (for example, the fifth of each month). Although the Soviets restricted prayer in the synagogue, they conducted little surveillance around rituals that took place in the domestic sphere. Therefore, on account of these very frequently held events, community prayer continued despite restrictions placed on institutional religion.

Bukharan Jews Today

As of 2020, only 100–200 Bukharan Jews still remain in Uzbekistan and fewer in Tajikistan. Others have resettled primarily in the United States and Israel, with some in Canada, Austria and Vienna. While no solid statistics are available, community leaders and the press report that 125,000 Bukharan Jews live in Israel and 75,000 in the United States; among them many are the children and grandchildren of immigrants from Central Asia.

In the United States, most Bukharan Jews are clustered in New York, primarily in Queens, where there are two major synagogues that also serve as community centers: Bukharian Jewish Community Center and Beth Gavriel Bukharian Jewish Center, both in Forest Hills. In addition to their active religious life, Bukharan Jewish culture has flourished in the United States with the newspaper Bukharian Times, music ensembles, restaurants, theater, the publication of cookbooks and a museum housed in the Queens Gymnasia school.

Bukharan Jewish Recipes to Try

Plov: One Pot Chicken and Rice

Dushpara: Bukharan Meat-Filled Dumplings

Bukharan Chicken and Herbed Rice

The post Who Are the Bukharan Jews? appeared first on My Jewish Learning.