How long can the country’s affairs be dictated by an organization dedicated to the interests of a foreign state?

by Neville Teller

On October 27, 2020, a year after former Lebanese prime minister Saad Hariri was dismissed from office, he was reappointed by President Michel Aoun. Despite Hariri’s previous inability to manage Lebanon’s growing economic and political chaos, he has one characteristic that sets him apart from many of his fellow politicians and even from his president. He is a long-standing and consistent opponent of Hezbollah. He has good reason. Hezbollah, it has been shown, was involved in the assassination of his father, Rafik Hariri, back in 2005.

Saad Hariri faces a totally unstable situation. Lebanon is a seething cauldron of popular discontent. It took decades for the head of steam to build up but finally, on October 17, 2019, the country blew its top. That was the day the government, in a desperate attempt to get a grip on the failing economy, announced that new taxes were to be imposed on an already poverty-stricken population, and that the cost of gasoline, tobacco, and internet calls such as What’sApp were to be hiked up.

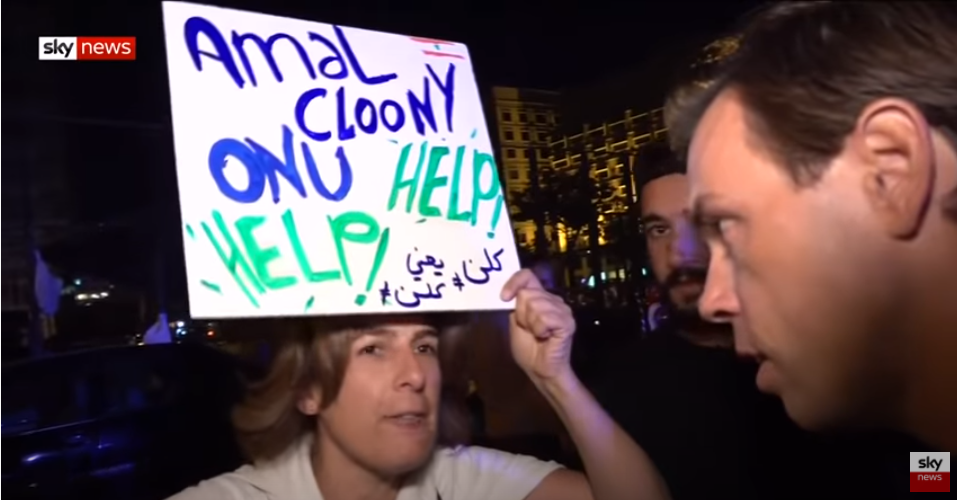

Crowds took to the streets. The proposed taxes were the trigger, but the underlying causes of the widespread fury soon emerged. They ranged from opposition to the basic system of government by religious affiliation ‒ a system established when Lebanon became independent of colonial France in 1944 ‒ to the stagnant economy, unemployment at very nearly 50 percent of the working population, endemic corruption in the public sector, and the totally inadequate provision of public services such as garbage collection, water, electricity and sanitation.

Come the first anniversary of the national uprising on October 17, 2020, anti-government protesters attended rallies the length and breadth of the country chanting “Revolution, revolution.” Yet revolution seems reluctant to show its face in Lebanon. The population, apparently ready for radical change, appears unable to bring it about.

In recent years the Lebanese people have endured a civil conflict, a long Syrian occupation, two wars with Israel, several economic crises, huge unemployment and political assassinations. The past twelve months alone has seen the country very nearly brought to its knees from a collapse of the currency, the onset of the coronavirus, the devastating explosion in Beirut port and two changes of prime minister. Yet the old ruling establishment ‒ moribund, corrupt and inefficient ‒ continues in power.

In the perception of a large proportion of the population enough is enough, and only root and branch reform will put the country back on its feet. Ever since that outburst of national rage in October 2019, demonstrators have been demanding the resignation of all those in power from the president down. All, without exception, are seen as the same power-hungry chieftains who led their followers into the 1975-1990 civil war before making peace with one another, and going on to enrich themselves.

One key factor in the malaise afflicting Lebanon is the fact that, embedded within the establishment structure, is the Iranian-supported Hezbollah organization. Founded by Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, shortly after he took power in 1979, it declared that its aims and purpose were entirely at one with Iran’s. Over the past few decades it has been consuming the political, military and administrative organs of the state, until only the outer shell of an independent sovereign country now remains. Many now believe that the Lebanese state and Hezbollah are in effect indistinguishable. It follows that if there is no place in a reformed Lebanon for those who run the present state, there is no place for Hezbollah.

During the first riots in 2019 protesters smashed the offices of Hezbollah MPs in southern Nabatieh. Before October was out, Hezbollah had rallied hundreds of supporters including an armed militia, and mounted a charge on protesters in central Beirut. As Amnesty International, making no distinction between Hezbollah and government forces, put it: “The largely peaceful protests since October 2019 have been met by the Lebanese military and security forces with beatings, teargas, rubber bullets, and at times live ammunition and pellets.”

France’s president Emmanuel Macron, who visited Lebanon twice in the aftermath of the Beirut port explosion, said the country’s ruling class had “betrayed” the people by failing to act swiftly and decisively against the party suspected of importing and storing the chemicals, Hezbollah.

If the Lebanese government has undertaken any positive action in the recent past, it is the decision to participate in the US-mediated talks aimed at demarcating the country’s maritime border with Israel. The situation is awkward. Following the 2006 conflict Israel and Lebanon are not technically at peace, but both are adhering to a UN-sponsored ceasefire. So the talks are being held at arm’s length.

All the same it is not Lebanon that is pledged to eliminate Israel, but Iran-backed Hezbollah, and the 2006 conflict was triggered by the armed forces of Hezbollah, not those of the state. It is scarcely surprising that Hezbollah and its main ally, the Amal Movement, are opposed to the maritime negotiations. They perceive the move, and perhaps they are correct, as an extension of the normalization agreements reached between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

All the same, some in Lebanon welcome the development. Ziad Assouad, a member of President Aoun’s party, said Lebanon’s dire economic situation meant that it should have no qualms about holding even direct negotiations with Israel.

Realistic thinking is called for within Lebanon’s administration. How long can the country’s affairs be dictated by an organization dedicated to the interests of a foreign state? If anyone is prepared to face down the vested interests within Lebanon linked to Hezbollah, it is Saad Hariri. Sooner or later the Lebanese establishment must recognize the inevitable. The time for fundamental change has arrived.

Neville Teller was born in London, read Modern History at Oxford University, and then had a varied career in marketing, general management, publishing, the Civil Service, and a national cancer charity. He began writing about the Middle East in the 1980s and has published four books on the subject. He is the Middle East correspondent for the Eurasia Review and writes regularly for various publications. He was made an MBE in 2006 “for services to broadcasting and to drama.”

Read more about: lebanon, Neville Teller