When my children were born, I assumed teaching them Torah would be easy. After all, I have a PhD in Talmud and am married to a rabbi. I worried about plenty of things—sleep schedules, tantrums, and other typical toddler woes—but Jewish education? That seemed simple.

How wrong I was.

As my children entered preschool, I began searching for resources to help my kids engage with Jewish texts and traditions. But while the bookstores shelves were filled with options for Christian children’s Bibles, the choices for Jewish families were limited. For my preschool aged children, the main options seemed to be retellings of Noah’s ark and a handful of other isolated stories. There was little that reflected the breadth and depth of Torah in a way that young children could truly access.

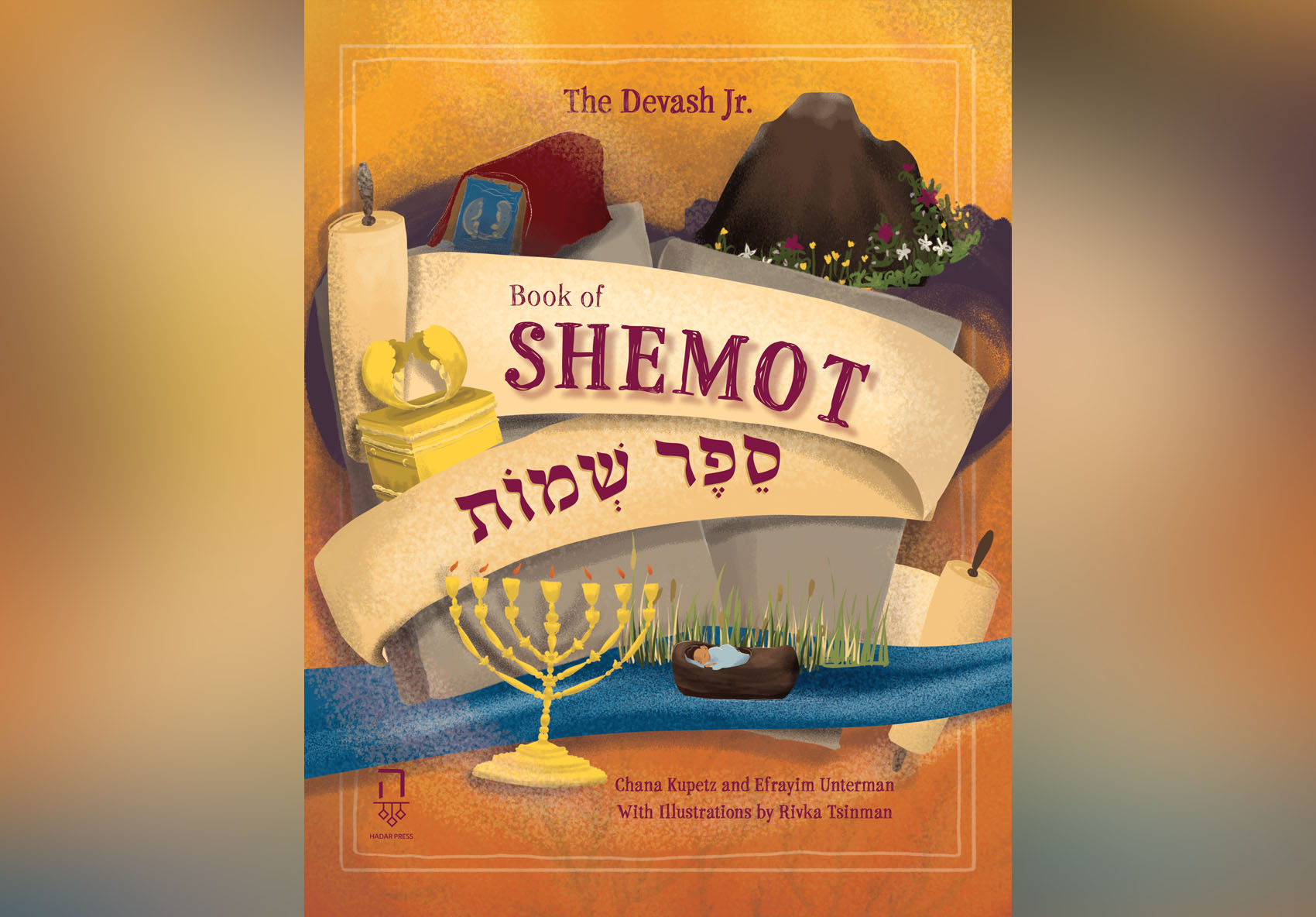

That’s why “The Devash Jr. Book of Shemot” feels so important. Rather than covering a single story, it introduces children to an entire book of the Torah. The text is divided into weekly parshiyot (Torah portions), mirroring the annual Torah reading cycle. This structure makes it easy for families with young children to read the weekly parasha together. The book is designed for ages three to seven, retelling each portion in clear, kid-friendly language paired with vivid illustrations. At the end of each section, there are also suggestions for how to connect the story to children’s everyday experiences.

Like many children’s Bibles, “The Devash Jr. Book of Shemot” summarizes the events, main ideas, or teachings of each parasha rather than providing a direct translation. (For families who want engagement with the literal words of the Torah, each section also highlights specific verses, providing them in both Hebrew and English.) The retellings emphasize connections to kids’ own experiences, presenting ideas in ways they can easily understand. For example, the book explains the commandment to return lost property as follows: “If you find a lost object, you have to return it, even if you’re not friends with the owner.” This framing speaks to the realities of a child’s world and the considerations that might be most relevant to them, such as themes of friendship or fairness.

The retellings emphasize connections to kids’ own experiences, presenting ideas in ways they can easily understand.

Of course, the ultimate test of any children’s resource is how kids respond. My children, ages four and six, are always excited when any new book arrives, and they eagerly dove into the first few parshiyot, which tell the story of baby Moses and his later call to lead the Israelites out of Egypt. They were already familiar with this story from our Passover celebrations, and the illustrations helped bring it to life. It was harder to hold their attention in some of the later portions, like those detailing the priestly garments or the construction of the Mishkan (Tabernacle), but the artwork helped sustain their curiosity even when the text was less narrative.

Interestingly, neither child has asked to reread the book, which is unusual in our home. They clearly experience it differently from the other stories we read, including picture books that tell a single story from the Torah, like Noah’s ark. I think this is partly due to the book’s presentation. It is physically large and lengthy. Children who are used to reading short stories may find its scale a bit overwhelming and be unsure where to begin or exactly how to engage with it. Furthermore, even in its most narrative sections, the text doesn’t follow the familiar arc of a storybook with a clear beginning, narrative arc, and resolution. That makes sense, since it mimics the structure and organization of the Torah itself, but it means parents need to be intentional about how they use it.

For that reason, I see “The Devash Jr. Book of Shemot” as a resource for parent-led learning rather than independent reading. It works best when integrated into family rituals or used as the foundation to create new practices, such as a Shabbat afternoon story time. And it comes out at the perfect time, since Jewish communities around the world will begin reading Shemot in just a few weeks.

It is worth noting that “Devash Jr.” makes specific choices about language and interpretation. It uses Hebrew names throughout (e.g., Benei Yisrael instead of the Israelites) and often provides Hebrew transliterations alongside English terms. It also incorporates elements of traditional interpretation and observance; for example, when introducing the commandment not to cook a kid in its mother’s milk (Ex. 23:19), it explains that meat and milk cannot be cooked or eaten together—a detail not explicit in the Torah text, but which becomes a normative part of keeping kosher. These choices reflect Hadar’s halakhic, egalitarian approach, but may not align with every family’s practice, goals, or orientation.

Overall, I was impressed by “The Devash Jr. Book of Shemot,” and hope that the series will continue with all five books. It succeeds in making Torah accessible to young children while honoring the text and its structure. For families with an existing Shabbat rhythm—or those looking to create one—it offers a meaningful way to bring Torah into the lives of our youngest learners. Most importantly, it sends a powerful message: Our children are full members of this tradition, and their engagement matters. The Torah is their heritage, and “The Devash Jr. Book of Shemot” makes that clear by creating a version of the text just for them.

Deborah Barer is Senior Faculty at the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America.