“I have sworn upon the altar of God, eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”-Thomas Jefferson

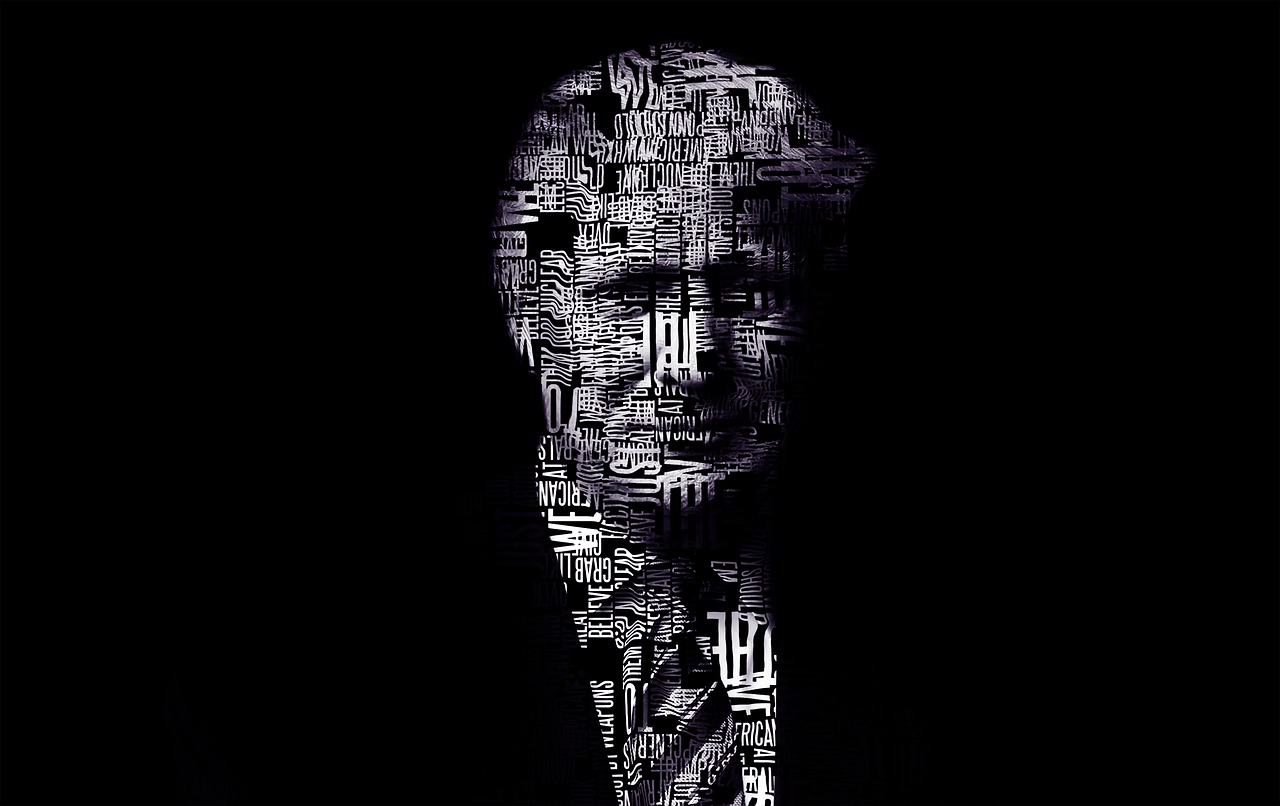

Once upon a time, Americans were still being instructed to value a life of the mind. Then, Ralph Waldo Emerson, following Thomas Jefferson, had called sensibly upon the young country to embrace “plain living and high thinking.” Today, this earlier plea for enhanced personal and social equilibrium has been discarded, even ridiculed, replaced by shameless exhortations to follow a dissembling president. If not worrisome enough, this president – a self-described “very stable genius”- is loudly and proudly illiterate.

Credo quia absurdum, warned the ancient philosopher Tertullian. “I believe because it is absurd.”

But there is much more to tell. It was Donald Trump who commented several times during the 1916 campaign: “I love the poorly educated.”For anyone seeking an apt historical precedent for such a patently retrograde observation, there is the infamous statement by Third Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels: “Intellect rots the brain.”

Still further explanation is required, one that can offer us both lucidity and purpose. To begin at the beginning, we must examine America’s longstanding orientation to formal education. In these United States, from every student’s very first day in grade school, a core message is received: “Your education isn’t going to be about anything pleasant or fascinating or ennobling. It will be about the statutory fulfillment of assorted institutional and personal obligations. Hopefully, it will also help prepare you for a job. Don’t expect anything more.”

So, dear students, continues this implicit but conspicuous message, “Sit back, be obedient and just try not to shoot anyone.”

Remaining unhidden, not only our multiple systems of education, but also our presidential elections, are shaped by certain primal disfigurements. In essence, America’s cumulative political ambitions remain integrally bound up with variously embarrassing and mutually-reinforcing simplifications. In this most revealingly barren sphere of American public life, one driven by stupefying clichés and empty witticisms, even the most witting buffoon can make himself or herself electable. This is the case, inter alia, at least as long as he or she has somehow managed to accumulate great wealth, and (as another evident sine qua non) to avoid being labeled an “intellectual.”

In Trump’s America, no denigrating epithet could conceivably be more damning.

A nefarious evolution is underway. From Thomas Jefferson to Ralph Waldo Emerson to the present moment, America’s public declension, along with pertinent bifurcations, has been both obvious and disabling. Money good; intellect bad. Amid our corrosive national ethos of competitive achievement, wealth, however acquired, signifies success. Always, prima facie, it displays irrefutable evidence of “being smart.” Here, upon examination, the tortuous circularity of misguided reasoning is baneful yet unambiguous.

Plausibly, both Thomas Jefferson and American Transcendentalist thinker Ralph Waldo Emerson would have been shaken. Our early presidents and philosophers, after all, were often people of some genuine accomplishment and original thought. We remember them, surely, not for any glittering successes in the vulgar marketplace of mundane things to be bought and sold, but instead for their auspicious presence in a mind-centered marketplace of ideas.

“One must never seek the Higher Man in the marketplace” warns Friedrich Nietzsche’s Zarathustra.

Why, then, are American presidential politics so profoundly demeaning and so utterly debased? Where, exactly, have we gone wrong? Perhaps we ought to approach these core questions as “physicians” of the national body politic. Accordingly, as with any other insidious pathology, we must identify the disease before we can be rid of it.

But what exactly is this underlying “disease”?

There is an answer. It begins, as does every systematic or scientific assessment, with the individual, with the microcosm. Inevitably, our American electorate, here the relevant macrocosm, can never rise any higher than the combined capacities of its members. “When the throne sits on mud,” recognizes Zarathustra, “mud sits on the throne.”

Ultimately, every democracy must represent the sum total of its constituent souls;[1] that is, those still-hopeful citizens who would seek some sort or other of “redemption.” In our deeply fractionated American republic, however, We the people – more and more desperate for a seemingly last chance to “fit in” and “get respect” – inhabit a palpably vast wasteland of lost opportunity. Within this grievously grim and contrived human society, we (T S Eliot’s “hollow men” or women) are chained to more-or-less exhausting and tasks, buffeted incessantly by a hideously dreary profanity and watched over by a smugly demeaning theology of engineered consumption.

There is more. Literally bored to death by the prosaic obligations of everyday American life, and beaten down by the grinding struggle to “stay positive” while suffocating in traffic and while completing interminable forms of inane paperwork, Americans grasp anxiously for almost any identifiable lifeline of intoxication or distraction. Unsurprisingly, our most publicized national debates are now about guns and killing, and never about literature, ideas, art or beauty. Within this vast and still-growing intellectual wasteland, huge segments of an unhappy population are perpetually drowning in drugs, submerged deeply enough to swallow entire millennia of human achievement and whole oceans of sacred poetry/

What else should we expect to endure amid the breathless American rhythms of circus-like conformance, submission and debasement? More than anything else, We the people have learned something crass and lethal. We have learned to cheerlessly embrace a corrupted and directionless national society, one that offers precious little in the way of any meaningful personal fulfillment. Let us be candid. Now, more than ever, Americans “don’t get no satisfaction.”

As a people, there can be little doubt, we unhesitatingly accept decline, without serious protest and without even a murmur of discernible courage. Above all, perhaps, Americans in the Trump Era continue to think aggressively against history, viscerally, immensely pleased that virtually no one takes the trouble to read or learn anything valuable. Ironically, even the most affluent Americans now inhabit this loneliest of crowds, living out their depressingly imitative lives at hotels and airports, pushed forward not by any once-lofty goals, but instead by coffee, alcohol, exercise equipment, and (representing the ultimate “reward” of modern America) accumulating frequent flier miles.

It is remarkably small wonder that millions of Americans cling desperately to their smart phones or derivative “personal devices.” Filled with a deepening horror of sometime having to be left alone with themselves, these virtually connected millions are clearly frantic to claim membership in the anonymous American public mass. Earlier, back in the 19th century, Soren Kierkegaard, had foreseen and understood this deadly “mass.”

“The crowd,” opined the prophetic Danish philosopher succinctly, “is untruth.”

“I belong, therefore I am.” This is not what French philosopher René Descartes had in mind back in the 17th century, when he so insightfully urged greater thought and(as indispensable corollary) greater doubt. This is also, inherently, a very sad credo. Unhesitatingly, it almost shrieks that social acceptance is equivalent to physical survival and that even the most ostentatiously pretended pleasures of inclusion are worth pursuing.

Desperately worth pursuing.

Should there remain any doubts about such a plainly pathetic credo, one need only consult the latest suicide statistics for the United States. To reduce these revealing numbers will require far more than silly and sterile Trumpian promises to “make America great again.” Above all, it will require a citizenry that finally wants more for itself than to chant evident gibberish in chorus.

There is more. A push-button metaphysics of “apps “reigns supreme in America. At its core, the immense attraction of this infantile social networking ethos stems in part from America’s expansively machine-like existence. Within this icily robotic universe, every hint of human passion must be suitably directed along certain ritualistically uniform pathways.

And woe to any citizen who would dare stray from this vicarious route.

Naturally, as we may still argue quite correctly, all human beings are the creators of their interdependent machines, not their servants. Yet, there does exist today an implicit and simultaneously grotesque reciprocity between creator and creation, an elaborate and potentially murderous pantomime between the users and the used. This is a reciprocity that needs to be carefully studied before it can be reversed.

Adrenalized, our fevered American society is making a machine out of Man and Woman. Rapidly, in a flagrantly unforgivable inversion of Genesis, it may soon seem credible that we have been created in the image of the machine. Mustn’t we then ask, as residually sober Emersonian thinkers, Freudian soul searchers and Cartesian doubters, “What sort of redemption is this?”

For the moment, Americans remain grinning but hapless captives in a deliriously noisy and airless crowd. Proudly disclaiming any meaningful interior life, they proceed tentatively, and in every existential sphere, at the lowest common denominator. Or expressed in more palpable terms, our air, rail, and land travel has become insufferable and positively screams for remediation.

Trumpian red hats notwithstanding, what sort of “greatness” is this?

There is more. Our vaunted universities are in much the same sort of decline. Once regarded as a last remaining beacon of some genuine intellectual life, they are typically bereft of anything that might even hint at serious learning. This can hardly be unexpected, however, as entire legions of newly-minted American professors receive their Ph.D. with barely a hint of demonstrated literacy or original accomplishment.

To the point, try to talk to a young professor about literature, art, music or philosophy. With precious few exceptions, it will be a brief and distinctly one-sided conversation.

For explanations, our transforming context is everything. In Trump’s America, the traditionally revered Western Canon of literature and art has been replaced by more reassuring emphases on football scores, university rankings and voyeuristic reality shows. Apart from their pervasive drunkenness and enthusiastically tasteless entertainments, the once-sacred spaces of “higher education” have become a commerce-driven pipeline, an all-consuming roadway to nonsensical and unsatisfying jobs.

Could anyone reasonably doubt this conclusion?

There is more. For most of our young people, learning has become an inconvenient but mandated commodity, nothing else. At the same time, as everyone can readily understand, commodities exist for only one purpose. They are there, like the next batch of mass-produced college graduates, to be bought and sold.

More than ever before, American is about Nietzsche’s marketplace.

Though faced with markedly genuine threats of war, illness, impoverishment and terror, millions of Americans still prefer to amuse themselves by resorting to various forms of morbid excitement, inedible or tangibly injurious foods and by the blatantly inane repetitions of an increasingly vacant political discourse. Not a day goes by that we don’t notice some premonitory sign of impending catastrophe. Still, our anesthetized Trumpian country continues to impose upon its exhausted and manipulated people a shamelessly open devaluation of serious thought and a continuously breakneck pace of unrelieved work.

Small wonder that “No Vacancy” signs now hang securely outside our psychiatric hospitals, our childcare centers and, above all, at our prisons.

Soon, even if we should somehow manage to avoid nuclear war and nuclear terrorism, the swaying of the American ship will become so violent that even the hardiest lamps will be overturned. Then, the phantoms of great ships of state, once laden with silver and gold, may no longer lie forgotten. Then, perhaps, we will finally understand that the circumstances that had once sent the compositions of Homer, Maimonides, Goethe, Milton, Shakespeare, Freud and Kafka to join the disintegrating works of long forgotten poets were neither unique nor transient.

In an 1897 essay titled “On Being Human,” Woodrow Wilson inquired sensibly about the authenticity of America. “Is it even open to us to choose to be genuine?” he asked. This president had answered “yes,” but only if Americans first refused to stoop to join the injurious “herds” of mass society. Otherwise, as Wilson had already understood, an entire society would be left bloodless, a skeleton, dead also with that rusty demise of broken machinery, more hideous even than the inevitable decompositions of each individual person.

In all societies, as Jefferson, Emerson and assorted others had recognized, the scrupulous care of each individual human soul is most important. Meaningfully, there can be a “better”American soul, and a correspondingly improved American politics, but not until we first acknowledge a compelling prior obligation. This is a far-reaching national responsibility to overcome the staggering barriers of Trumpian crowd culture and to embrace once again the liberating imperatives of “high thinking.”

The only alternative is to continue to quash any residual thought. But that choice would only forge a resigned peace with America’s still-expanding tyranny over the “mind” of its citizens. In short order, it would represent a broadly lethal and unforgivable choice.

Louis René Beres was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971), and is Emeritus Professor of International Law at Purdue. His twelfth book, Surviving Amid Chaos: Israel’s Nuclear Strategy, was published in 2016. His other writings have been published in Harvard National Security Journal; Yale Global Online; World Politics (Princeton); Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists; Israel Defense; Parameters: Journal of the US Army War College; Special Warfare; Oxford University Press; The Jerusalem Post; Infinity Journal; BESA Perspectives; US News & World Report; The Hill; and The Atlantic.

His Terrorism and Global Security: The Nuclear Threat (Westview, first edition, 1979) was one of the first scholarly books to deal specifically with nuclear

This article was first published in Modern Diplomacy