Tel Aviv University’s groundbreaking discovery in prehistoric archaeology provides evidence for advanced cognitive ability in 170,000-year-old early humans.

The researchers constructed a software-based smoke dispersal simulation model and applied it to a known archaeological site in a first-of-its-kind investigation. They discovered that the early humans who inhabited the cave had put their hearth in the best location – maximizing the use of the fire for their activities and needs while exposing them to the least amount of smoke possible.

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Yafit Kedar, a Ph.D. student, and Prof. Ran Barkai of TAU’s Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures argue that the use of fire by early humans has been a subject of intense dispute among experts for many years.

They raised questions such as: When did humans develop the ability to manage and ignite a fire at will? When did they start using it on a regular basis? Did they make efficient use of the cave’s interior space with respect to the fire? While all experts agree that modern people were capable of all of these tasks, disagreements persist on the capacities and skills of earlier forms of humanity.

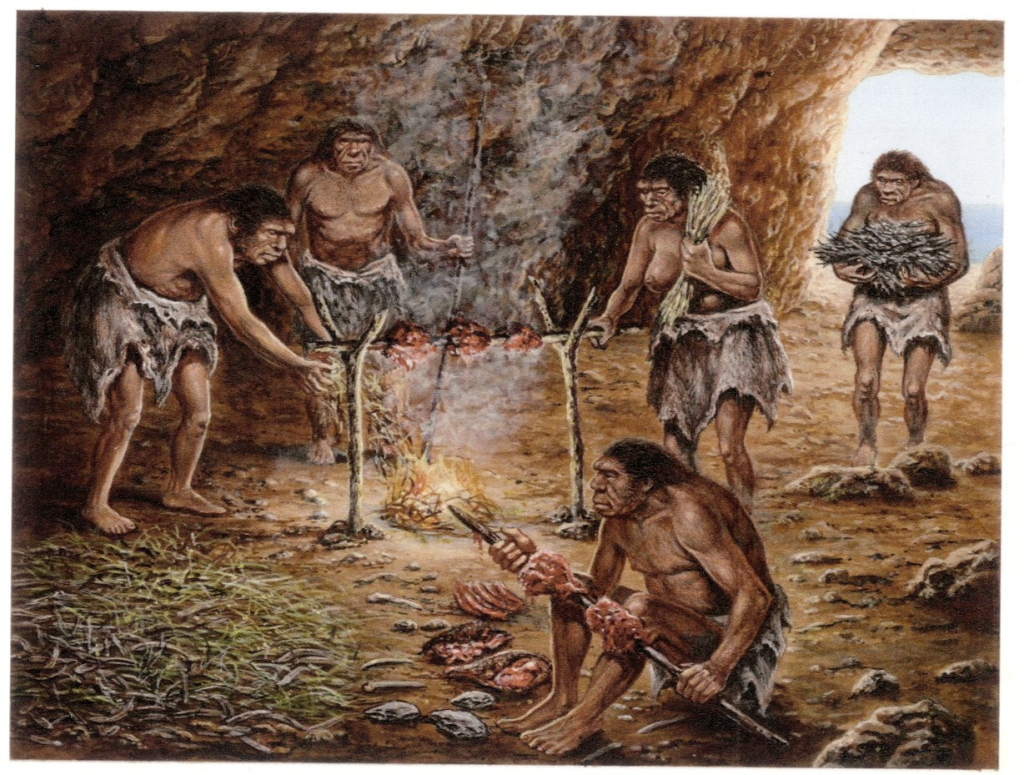

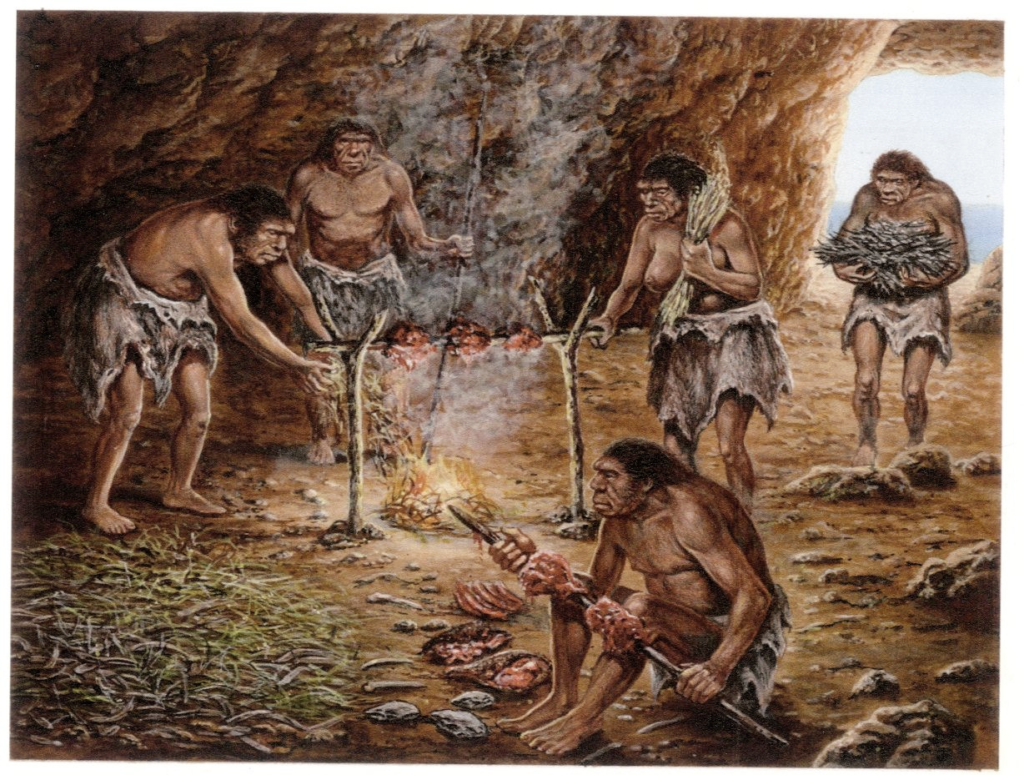

Kedar Yafit explained: “The position of hearths in caves occupied by early humans for extended periods of time is a point of contention in the argument. Numerous caves include multilayered hearths, showing that fires were burned at the same location for an extended period of time.

“In prior research, we discovered that the ideal site for least smoke exposure in the winter was at the back of the cave, utilizing a software-based model of air circulation in caves and a simulator of smoke dispersion in a closed space. The cave’s entrance was the least desirable site.”

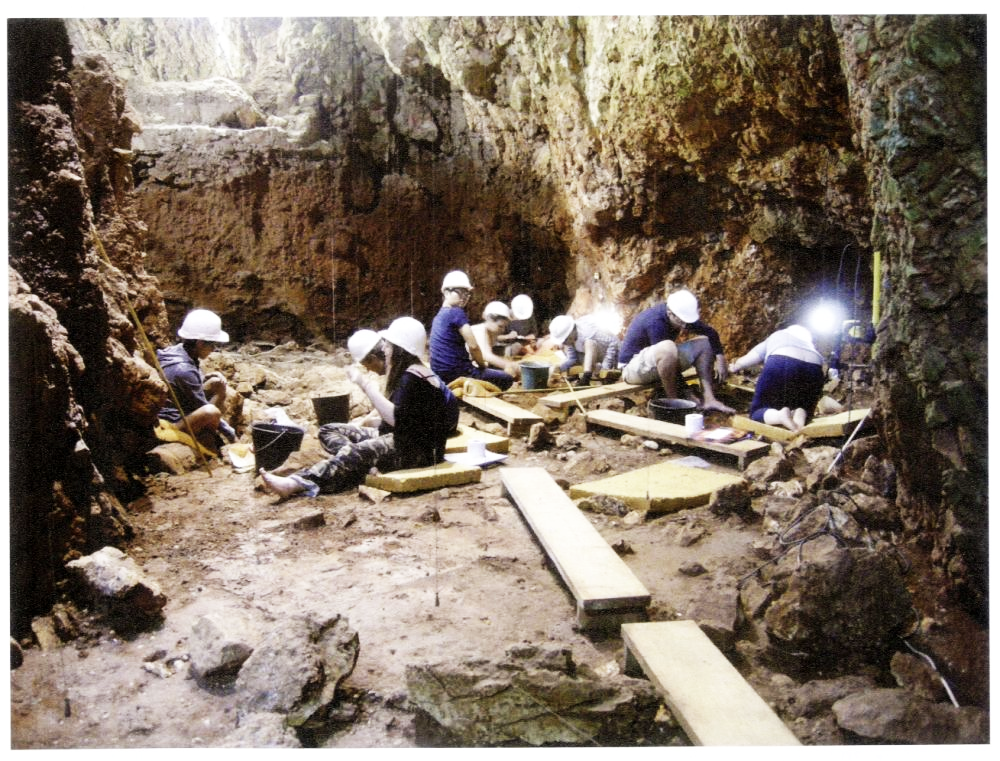

The new study applied the researchers’ smoke dispersion model to a well-studied prehistoric site – the Lazaret Cave in southeastern France, which was inhabited by early people between 170-150 thousand years ago.

Kedar Yafit: “According to our model, which is based on past research, positioning the hearth at the back of the cave would have minimized smoke density, allowing smoke to circulate out of the cave directly next to the ceiling.

“However, according to the archaeological layers we analyzed, the hearth was positioned in the cave’s middle. We sought to ascertain why the residents chose this location and whether smoke dispersion played a role in the cave’s spatial segmentation into activity sections.”

To address these concerns, the researchers ran a series of smoke dispersion simulations for 16 possible fireplace positions throughout the 290-square-meter cave. They examined smoke intensity throughout the cave for each hypothetical hearth using thousands of simulated sensors spaced 50cm apart from the floor to a height of 1.5m.

To better understand the health consequences of smoke exposure, measurements were made and compared to the World Health Organization’s average smoke exposure recommendations.

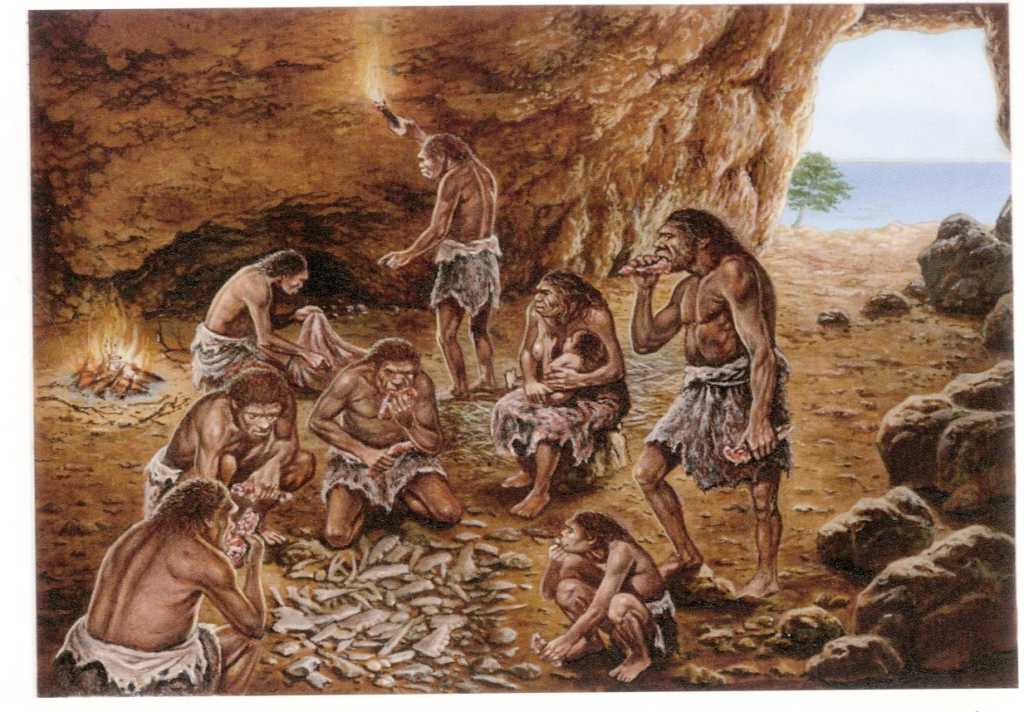

For each hearth, four activity zones were mapped in the cave: a red zone that is essentially off-limits due to the high smoke density; a yellow zone that is suitable for short-term occupation of several minutes; a green zone that is suitable for long-term occupation of several hours or days; and a blue zone that is essentially smoke-free.

Yafit and Gil Kedar: “We discovered that when the hearth is positioned toward the back of the cave, the average smoke density, as determined by the number of particles per spatial unit, is indeed minimal – exactly as anticipated by our model. However, we noticed that in this condition, the area with the lowest smoke density, which is the most conducive to sustained activity, is quite remote from the fireplace.

The earliest humans required a balance – a hearth near which they could work, cook, eat, sleep, gather, and warm themselves while being exposed to the least amount of smoke possible. Finally, after weighing all of their demands – daily activities vs. the dangers of smoke exposure – the residents located their hearth in the cave’s best location.”

The study found a 25-square-meter region within the cave as the best location for the hearth in order to reap its benefits while avoiding excessive smoke exposure. Surprisingly, throughout the several levels analyzed in this study, the early humans did indeed place their hearth in this spot.

Prof. Barkai summarizes: “Our study demonstrates that early humans were able to determine the optimal site for their hearth and manage the cave’s space without the aid of sensors or simulators as early as 170,000 years ago – much before the arrival of modern humans in Europe. This capacity demonstrates resourcefulness, expertise, and deliberate action, as well as an understanding of the health consequences of smoking exposure. Additionally, the simulation model we built can aid archaeologists digging new sites by allowing them to locate hearths and activity zones in the most advantageous locations.”

The researchers want to use this model in future studies to explore the effect of different fuels on smoke dispersion, the use of the cave with an active hearth at various times of the year, the use of multiple hearths concurrently, and other pertinent concerns.