“Nobody Wants This,” a rom-com Netflix series starring Adam Brody as a charming Los Angeles rabbi who falls for a blond, agnostic sex and dating podcaster played by Kristen Bell, is based on a true story — kind of.

Erin Foster, the creator of the show, is a blond Los Angeles native who found her match in a Jew, albeit not a rabbi — her husband is record-label owner Simon Tikhman — and converted for him. Like her protagonist Joanne (Bell), she also “got the ick” when her Jewish then-boyfriend eagerly tried to impress her mother with a bouquet of oversized sunflowers.

In other words, Foster is a “shiksa” to the perennial nice Jewish boy. “Shiksa,” as Joanne quickly discovers in “Nobody Wants This,” is a Yiddish-origin pejorative used by Jews to describe non-Jewish white women with varying degrees of blond hair. “Shiksa” was also the original title of the 10-episode series, which premieres on Netflix on Thursday.

Reaction to the hotly anticipated series has ranged. After the trailer launched earlier this month, fans of Brody marveled at his portrayal of a “hot rabbi,” and one early reviewer praised the show as “a smart and sexy story where Jews are the plotline, not the punchline.” Others bristled at what they saw as stereotypes about Jewish women.

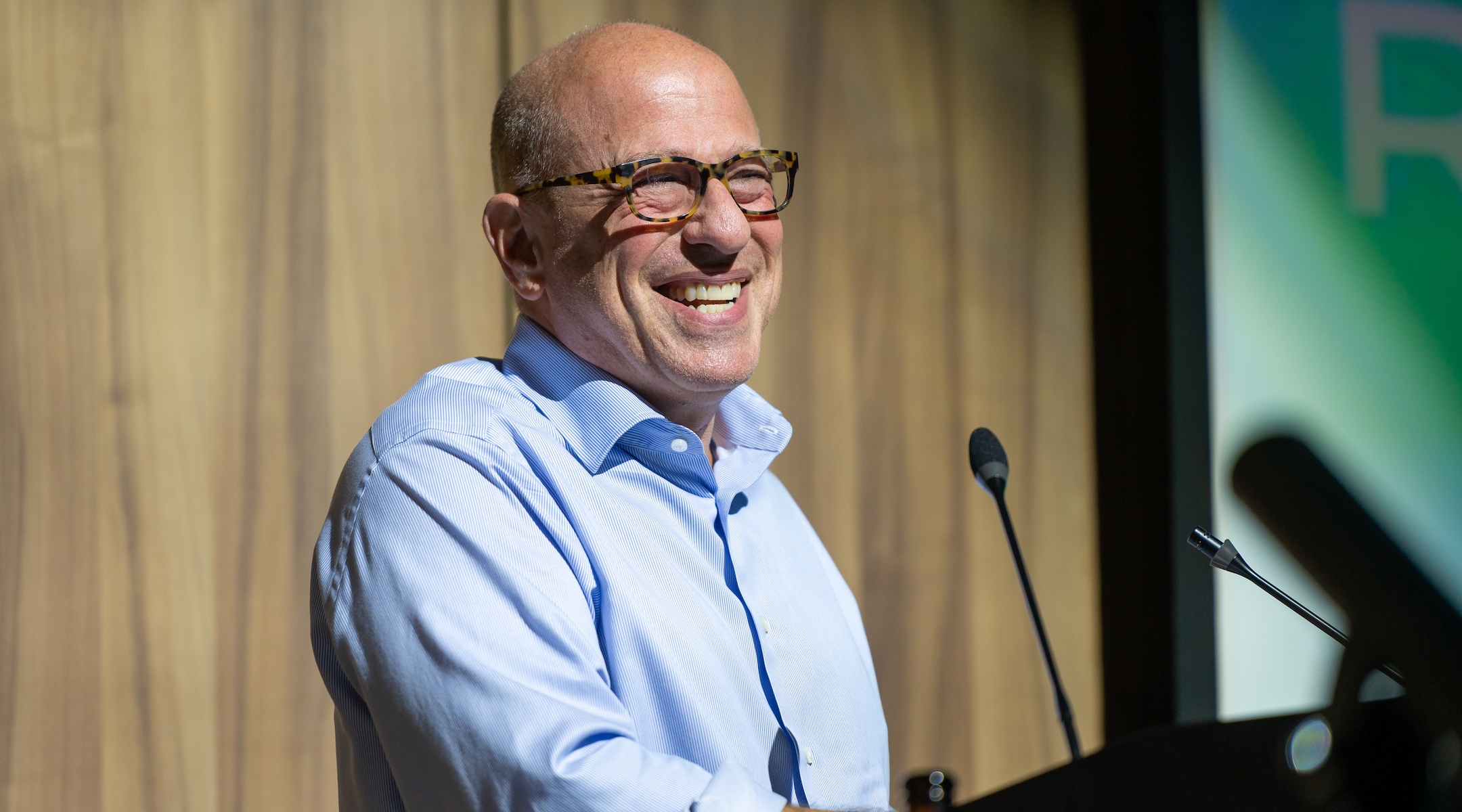

Steve Leder, the former senior rabbi of Wilshire Boulevard Temple in Los Angeles, supplied his advice to the cast and crew as a consultant rabbi. He had his own connection to the real-life love story — Foster converted to Judaism in his synagogue. (“Temple can be very boring,” Foster recently told New York Magazine, but she praised the eight-week Choosing Judaism course she took with her husband before their wedding.)

Leder was tasked with vetting the Jewishness on screen, from the schedule of earnest rabbi Noah (Brody) to the pronunciation of Hebrew words to the ordering of candles, wine and bread for Shabbat. Brody has gained fame by portraying Jewish characters on screen, most notably Seth Cohen in “The O.C.” and, more recently, Seth Morris in “Fleishman Is in Trouble.” But in real life, he says he “barely got bar mitzvahed and retained nothing from it,” and had Leder’s help alongside his own journey through books, podcasts and documentaries about Judaism.

Executive Producer Erin Foster and Adam Brody as Rabbi Noah Roklov in Netflix’s “Nobody Wants This.” (Stefania Rosini/Netflix)

“Anything in the series that is, for lack of a better way to put it, overtly Jewish — I did my best to make sure it was done with authenticity and respect,” Leder told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

The central tension of the show — whether Noah can marry a non-Jew while continuing on his path as a rabbi — is also a realistic one, said Leder. While some rabbis marry non-Jews, he said it’s more common that their partners eventually convert. Traditional Jewish law, known as halacha, prohibits marriage between Jews and non-Jews.

Still, “Nobody Wants This” comes out during a time when American Jewish institutions are increasingly accepting intermarried rabbis. Hebrew Union College, the rabbinical seminary of the Reform movement, announced in June that it was dropping its ban on interfaith relationships for rabbinical students. The Reform movement is by far the largest denomination in the United States, with four in 10 members married to non-Jews. Reform rabbis have never been prohibited from intermarrying.

HUC’s decision followed similar shifts at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College and the pluralistic Hebrew College. The Conservative movement’s two seminaries continue to ban interfaith relationships, a position the movement reaffirmed this year in keeping with the denomination’s commitment to halacha, but since 2018 its rabbis have been allowed to attend interfaith weddings. (Noah’s denomination in “Nobody Wants This” is left ambiguous, but his practices suggest that his synagogue is most likely Reform.)

The institutions follow a norm among American Jews, who have increasingly intermarried over recent decades, according to a 2020 Pew survey. Religious intermarriage is rising across the U.S. more broadly, and Jews are far less religious than American adults as a whole, by the conventional standards of attending religious services and believing in God.

Steve Leder, the senior rabbi of Wilshire Boulevard Temple in Los Angeles, advised the series. (Courtesy)

A longstanding worry among Jewish leaders about the community’s continuity — seen as threatened by intermarriage and demographic decline — has also been mitigated by research into how intermarried families actually raise their children. The Pew survey found that most intermarried parents are raising their children with some form of Jewish identity.

But you wouldn’t guess that trend of acceptance from Noah’s Jewish circle. As much as he fears rejection by his congregation, he is nearly as cowed by judgment from his own family — primarily the women, and most of all his mother Bina (played by Broadway star Tovah Feldshuh, who also played a Jewish mother in “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend”). Bina is comforting Noah’s Jewish recent ex-girlfriend when she says, “Everybody knows that shiksas are just for practice.”

Bina is overbearing, demanding and tries to kiss her son on the mouth. Noah’s sister-in-law Esther (Jackie Tohn) is similarly unyielding — dominating over her helpless husband Sasha (Timothy Simons) and drawing sharply demeaning contrasts to Joanne, whom she refers to as “Whore #1” (Joanne’s sister Morgan, played by Justine Lupe, is “Whore #2”). The only Jewish woman who immediately welcomes Joanne is a rabbi she meets briefly at Noah’s former camp, who is, coincidentally, also blond.

The stereotypes of Jewish women can sometimes lean into shtick, necessary as they are for the show’s comedic contrast between the fun, outspoken, sex-positive shiksa and the severe, withholding Jewish women who view her as a threat. But Leder said that while their exaggerated tendencies were written for a laugh, the Jews were in on the joke.

“Fundamentally, those characters were based on real people,” said Leder. “You know, there’s this old joke about the Jews… ‘The Jews are like everyone else, just more so.’ So that’s sort of television, right — it’s real but more so.”

Support the Jewish Telegraphic Agency

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, (JR) can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.