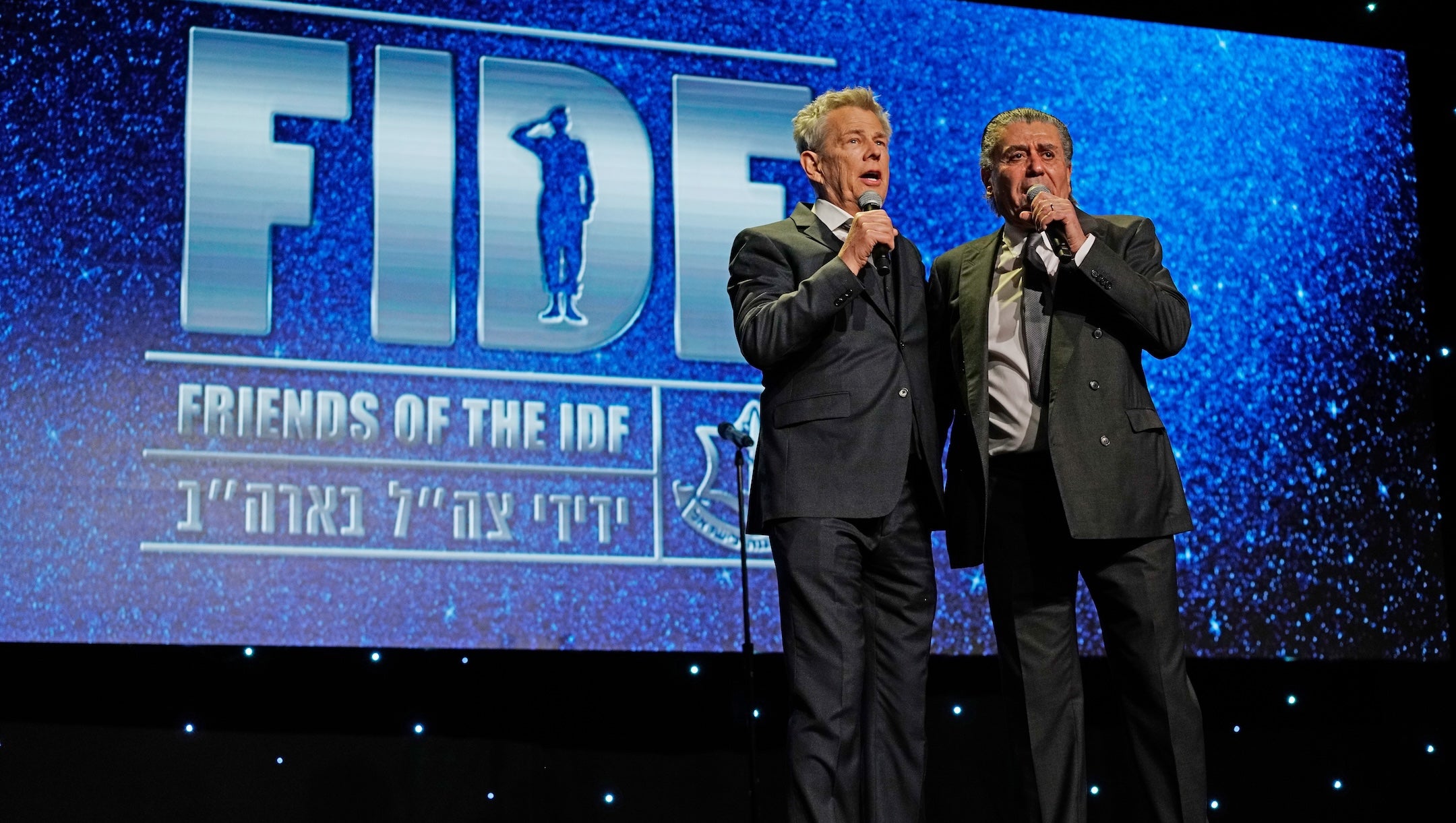

After a crisis that led to the resignation of its top leadership last month, Friends of the Israel Defense Forces was looking to rehabilitate its reputation.

In his first address to supporters, the group’s new CEO, retired Israeli general Nadav Padan, pledged to turn the page and focus on the future. He also leaned on one of the organization’s most longstanding and potent claims: that FIDF is the only group officially authorized by the Israeli military to collect donations on behalf of its soldiers in the United States.

Days later, FIDF published a thank-you letter from the IDF’s chief of staff, underscoring its special status. It was a powerful message in a crowded field, especially since the war in Gaza began, when American donors have been inundated with appeals to support Israeli troops, from grassroots crowdfunding campaigns to multimillion-dollar galas.

Since 2017, that claim of exclusive endorsement has helped FIDF raise roughly $1 billion. At a time when dozens of organizations are vying for American donations on behalf of Israeli soldiers, that claim gives it a potent marketing edge.

But when the Jewish Telegraphic Agency asked the IDF spokesperson’s office to confirm the claim, the military declined to do so, which suggests the reality is more complicated than the group presents.

The military instead referred questions to the Association for Israel’s Soldiers, its official charitable partner in Israel. The group did not respond to an inquiry from (JEWISH REVIEW).

Another charity, American Friends of LIBI, claims it has authorization equivalent to FIDF’s. LIBI refers to one of three Israeli charities that merged by 2016 to form the Association for Israel’s Soldiers. “It’s marketing — we are both authorized. They are misstating the situation,” the group’s vice chairman, Shimshon Erenfeld, told (JEWISH REVIEW).

After being contacted by (JEWISH REVIEW), FIDF acknowledged American Friends of LIBI’s status, saying its claim of exclusivity was based on a certificate issued by the IDF in 2019. “Thank you for making us aware of the status of American Friends of LIBI (LIBI USA). We commend them for their efforts to care for the soldiers of the IDF and wish them continued success,” a spokesperson said in an email in July.

For donors, the picture is even murkier: Beyond FIDF and LIBI, there are dozens of other groups that contribute meaningfully to Israeli soldiers.

One witness to the impact of FIDF’s attempt to monopolize fundraising is Adi Vaxman, the head of Operation Israel, an American group set up soon after the war in Gaza broke out.

“When donors hear exclusivity claims or misleading messages about wartime support, they hesitate,” she said. “They assume that organizations like ours may not be recognized, authorized or effective, when in fact we are often the first to respond and able to make a much larger impact on the ground.”

Vaxman gave an example from the recent conflict between Israel and Iran when an Israeli commander asked for sleeping bags and basic gear for troops housed in an empty school.

“FIDF told him their process would take 30 to 90 days,” Vaxman said. “We filled the request within 24 hours.”

Israeli army Major General Nadav Padan, left, now the CEO of the Friends of the IDF, guides U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as they fly in an Israeli military helicopter over the Jordan Valley, June 23, 2019. (Abir Sultan/AFP via Getty Images)

For donors seeking the reassurance of Israeli endorsement, FIDF is hardly unique, as several other organizations also appear to carry an official imprimatur.

For example, the Association for Israel’s Soldiers directly solicits donations in the United States through online crowdfunding platforms like Jgive and IsraelGives. Virtually all Israeli charities focused on troops, from those serving lone soldiers to groups aiding in recovery from battle-related PTSD, receive American tax-exempt donations funneled through U.S.-based pass-through organizations such as PEF Israel Endowment Funds, the Jewish Communal Fund and the Central Fund of Israel.

Meanwhile, various individual Israeli military units have their own affiliated American fundraising arms, including American Friends of Unit 669, American Friends of Israel Navy SEALs, and Friends of Duvdevan.

The field has grown exponentially since the war in Gaza began. When the Israeli military mobilized hundreds of thousands of reserve soldiers, the scale of the logistical challenge quickly became apparent. There were not enough helmets, boots and other basic gear for everyone, including combat soldiers heading into battle.

In response, soldiers turned en masse to social media to solicit donations directly. Israeli civilians and Jews in the Diaspora answered the call, raising and shipping hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of gear over the following months. Much of the effort was coordinated with individual soldiers and their commanders, bypassing both the FIDF — which, as a policy, does not supply combat equipment — and the IDF’s central command, which has publicly denied that any shortages exist and threatened to penalize those who accept donations.

In the wake of the war, dozens of new and existing American tax-exempt charities positioned themselves to collect donations, buy equipment, and funnel it to Israeli soldiers. The rush created a murky environment in which donors often had no clear way to separate legitimate aid from opportunistic schemes. To bolster credibility, fundraisers circulated video testimonials from soldiers and even letters on official brigade and battalion letterhead.

One of the most prominent is Israel Gives, whose website showcases endorsements from Israel’s foreign minister and a senior Defense Ministry official, signs of political backing that few others can claim.

No group claims exclusivity — except for FIDF. For donors unfamiliar with Israel’s nonprofit terrain, the label “the only official” carries the implication that their contributions will be deployed efficiently and with the military’s explicit endorsement.

“At CharityWatch, we see charities playing fast and loose with the facts in their marketing claims on a regular basis,” she said, describing the field in general, not the discourse around support for Israel’s military. “Some charities lie outright, while others define words in ways that are extremely narrow or broad so they ‘technically’ aren’t lying. They know most donors will infer what they want them to infer based on how they frame a particular fact.”

Styron said that misleading or exaggerated marketing is rarely punished, even if it influences donor behavior. “A charity has to work really hard to get into legal trouble for its marketing claims,” she said, noting that regulators often lack the resources to investigate unless harm to donors is significant and clear-cut. That, she added, is why donors should be cautious about taking any charity’s promotional language at face value.

In the wake of the war, dozens of new and existing American tax-exempt charities collect donations, buy equipment and deliver it to Israeli soldiers. Above, a shipment of tactical boots for Israeli soldiers purchased by Boots For Israel using donated funds arrives at Israel’s Ben Gurion International Airport. (Courtesy)

Amid the proliferation of grassroots fundraising campaigns for Israeli soldiers, FIDF has moved to caution donors against what it describes as “unauthorized” efforts. Its leaders have urged supporters to give only through established, officially sanctioned channels — a stance that critics say unfairly discredits and undermines volunteer-driven initiatives.

“It is not only misleading, it’s actively harmful to the grassroots ecosystem that has played a vital role in Israel’s defense since Oct. 7,” Vaxman said. “In reality, dozens of grassroots groups, ours included, have been operating in close coordination with IDF commanders, logistics officers and special units to fulfill urgent wartime needs that official channels could not meet fast enough

She continued, “To suggest that only one organization is ‘authorized’ while ignoring the actual needs and solutions on the ground is irresponsible and dismissive of the tremendous work being done by Israeli and diaspora volunteers alike.”

Despite the intense competition and criticism, FIDF remains the 800-pound gorilla of Israel-related soldier philanthropy. In 2023 , it reported about $282 million in revenue and $336 million in assets, according to its latest IRS filing, putting it among the very largest Jewish charities in the United States.

But the group’s standing was shaken in July, when Ynet reported on the contents of a leaked internal investigation that alleged financial mismanagement, cronyism and a toxic workplace culture. The report described board chair Morey Levovitz as sidelining then-CEO Steve Weil, steering no-bid contracts to associates and declaring, “I run the show.”.

The leak rattled FIDF’s donor base. Some regional chapters reportedly froze contributions, and staff were privately warning of a potential exodus of donors. Within two weeks, both Levovitz and Weil resigned. FIDF moved quickly to install new leadership, naming longtime donor Nily Falic as national chair and Padan as chief executive, and to hire crisis communications specialists in a bid to reassure donors.

Announcing the start of his tenure, Padan wrote, “I reaffirm our exclusive partnership with the IDF. FIDF remains the one and only official organization in the United States authorized to raise charitable donations for Israel’s soldiers.”

Keep Jewish Stories in Focus.

(JEWISH REVIEW) has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.