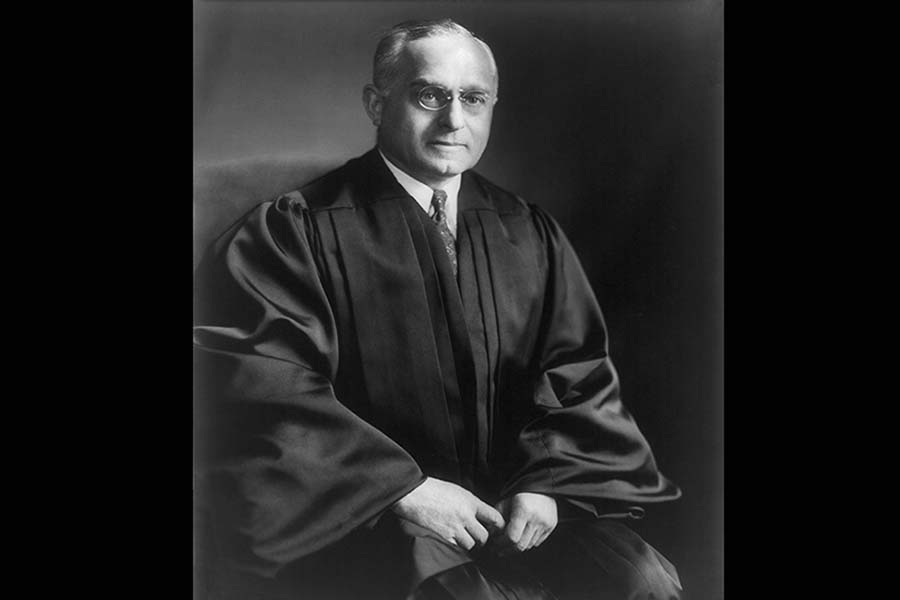

Editor’s note: In September, Jewish Press columnist Saul Jay Singer wrote an article on Felix Frankfurter to which Dr. Rafael Medoff – director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and the author of numerous books on the Holocaust – took great exception. He wrote a letter to the editor two weeks ago, to which Singer responded in last week’s issue.

Dr. Medoff asked to respond once again, so we decided to let the two of them duke it out in this week’s issue. We gave them both two opportunities to respond to each other in a series of 400 word-responses, with Singer – as the author of the original article – getting the final say. Below are their responses, with Dr. Medoff having the opening salvo.

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 0 });

Were the Jews who were closest to President Franklin D. Roosevelt justified in refraining from pressing him to rescue European Jews?

In his September 6th column, Saul Singer noted that Polish emissary Jan Karski described the mass murder of Europe’s Jews to Roosevelt, “who refused to take any action in response to his testimony.” Singer commented: “Thus, Frankfurter’s assessment that pushing the issue could not sway the president was, in retrospect, arguably correct.”

Singer made the same point in his October 30th letter, stating that FDR “was firm in refusing to bomb the tracks to Auschwitz or provide other assistance to the Jews, and Frankfurter clearly could have done nothing in this regard except anger the president.”

Fortunately, a different Jewish member of Roosevelt’s inner circle, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., did not succumb to fears of “angering the president.” In January 1944, Morgenthau directly confronted the president to plead for rescue action.

Morgenthau’s intervention was greatly strengthened by the fact that Jewish activists, too, refused to be intimidated by fear of “angering the president.” Rabbi Stephen S. Wise and others warned the Bergson Group that its newspaper ads and protest rallies (including the march by over 400 rabbis to the White House) would cause pogroms. Bergson forged ahead, mobilizing public and congressional pressure that made rescue a major issue – and a political hot potato.

Contrary to Mr. Singer’s speculation, Roosevelt was not “angered” when Morgenthau, backed by the public protests, approached him. In fact, quite the opposite: The president was swayed by the pressure from Morgenthau and his allies. FDR didn’t want to have an election-year controversy over the refugee issue. So he gave in to the pressure and established the War Refugee Board.

Although the president gave the Board only token funding (90 percent of its budget was supplied by private Jewish organizations) and often rejected or watered down its proposals, the Board still helped save more than 200,000 Jews in the final months of the war, in part by financing and organizing Raoul Wallenberg’s rescue activities in Nazi-occupied Budapest.

If Morgenthau had followed Frankfurter in refusing to approach the president for fear of “angering” him, there would have been no War Refugee Board and no Wallenberg rescue mission. It’s a good thing Morgenthau decided to try to sway FDR, instead of being paralyzed by fears of angering him.

Cordially,

Dr. Rafael Medoff

* * * * *

Dr. Medoff, again hypocritically, criticizes my “speculation” before proceeding to engage in rank speculation himself. I do not pretend to know what FDR would or would not have done under any set of variable circumstances and, significantly, neither does Medoff. I disagree with his position on the central question of whether Frankfurter could have made a difference in challenging FDR but, in that regard, I would respectfully refer him and your readers to an important sentence in the final paragraph of my previous letter:

“Whether Frankfurter could have, and should have, done more to help rescue European Jewry is a fair question subject to reasoned debate and discussion – though I must add that FDR was firm in refusing to bomb the tracks to Auschwitz or to provide other assistance to the Jews, and Frankfurter clearly could have done nothing in this regard except anger the president.”

I take further issue with Medoff’s characterization of Frankfurter as “paralyzed with fear”; that portrayal not only constitutes sheer speculation, which he apparently condemns in others but not himself, but is also wholly inconsistent with the essence of Frankfurter’s character, as manifested through decades of his public service in every meaningful way.

So certain is he that his opinion is the only viable one on this complex issue that he doesn’t even have the intellectual honesty to write “In my opinion…” or “As I see it…” Rather, he seems to see things only in black-and-white and to have no appreciation for the thorny competing imperatives which leaders such as Frankfurter faced in situations like these. Such is the life of some academics, who sit in comfort in their ivory towers and criticize the actions of leaders without ever having to face such difficult moral challenges themselves.

Of course, all this in no way detracts from the admiration we should all feel for Morgenthau’s decision to confront the president. However, Morgenthau was a cabinet officer whose very job description included advising the president, while Frankfurter was a Supreme Court justice and a personal friend who would be mixing into affairs that were not his official business. Different analysis? Perhaps, particularly since every relationship is different and few people knew FDR as well as Frankfurter.

Finally, I expected that Medoff would, at the very least, apologize for the deceptive parenthetical he used to mischaracterize my position. I am still waiting.

Saul Jay Singer

* * * * *

It’s sad when a civilized exchange of views deteriorates into mud-slinging. Overheated invective such as “hypocritical,” “deceptive,” “doesn’t have intellectual honesty,” “sits in comfort in ivory towers,” etc. adds nothing to the discussion.

There are two important historical issues at stake in this exchange. One is whether anything could have been accomplished if the Jews close to President Roosevelt had pressed him on the rescue issue. We already know the answer to that, from what Treasury Secretary Morgenthau accomplished, as I explained above.

The second issue is the question of why Felix Frankfurter was so reluctant to raise Jewish concerns with the president. The most detailed study of this aspect of Frankfurter may be found in the critically-acclaimed book Rabbis and Lawyers: The Journey from Torah to Constitution, by Professor Jerold S. Auerbach of Wellesley College.

He writes: “When Frankfurter came to the Court [in 1939], the plight of European Jews had become desperate, and the unwillingness of the American government to admit refugees fleeing from Nazi terror was evident. By then, however, his involvement in Jewish affairs, sporadic at best, had all but evaporated. During his first decade on the bench, coinciding with the Holocaust and the birth of Israel, there is little evidence that Frankfurter was active in, or especially concerned with, Jewish issues.”

Auerbach continues: “It might be argued (as Frankfurter himself claimed) that his sense of propriety about extrajudicial activity decisively inhibited his participation in Jewish affairs. Yet the range of Frankfurter’s political activism during his early years on the bench, even measured by the tolerant standards of that era, was extraordinary… [Nevertheless] Frankfurter would not utilize his position and contacts, or his irrepressible energy, in the service of Jewish needs during the most desperate years of Jewish history.”

Prof. Auerbach traces Frankfurter’s attitude to two factors: his “sycophantic adoration” of FDR, and his “ambivalence about the very meaning of his own Jewishness and its compatibility (or incompatibility) with his yearnings to be an American.” He writes, “He never resolved the acute tension between the claims of his Jewish heritage and his denial of its influence. The conflict remained with him as long as he lived…. His final instruction to his biographer just before he died suggested even more evocatively the meaning of Frankfurter’s silence on Jewish issues: ‘Let people see how much I loved Roosevelt,’ he insisted, ‘how much I loved my country.’”

Sincerely,

Dr. Rafael Medoff

* * * * *

What is truly sad is that, rather than acknowledging that there are two sides to this very difficult issue, Dr. Medoff cites at length one opinion, that of Professor Jerold Auerbach, as somehow being the final and definitive authority on this complex question, which he is not.

What is even sadder is Medoff’s persistence in misrepresenting what I wrote and then, when I had the temerity to call him on it, bemoaning that the exchange has “deteriorated into mud-slinging” and “overheated invective.” Such tactics are usually employed by those who are bereft of factual argument but cannot bring themselves to admit it.

Readers should know that this manner of misrepresentation appears to be Medoff’s modus operandi. See, for example, Richard A. Levy’s lengthy letter to the editor published in Defining Jewish Identity in America, Part 2 (Johns Hopkins University Press, March 1997), where he takes Medoff to task for relying on “the oldest trick in the book.” As he explains:

The trick, which is more commonly found in works of propaganda than of scholarship, starts with a deliberate misquotation. The text is carefully arranged to contain an obvious error, where the original had none. The planted error is then “discovered” with suitable expressions of horror. Finally, the discovery of the planted error is used to cast doubt on the credibility of the whole.

This is precisely what has happened in this case. For shame, Dr. Medoff.

Saul Jay Singer

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 25 });