Today, the Gemara asks: Why do I need all of these?

No, the Gemara is not downsizing and looking to rid itself of sweaters that it hasn’t worn in three years. Rather, it’s asking about a mishnah that teaches that s’chach (roofing materials) that would normally render a sukkah invalid are fine if they are located at the outer edge of the sukkah and are less than four cubits wide. Why? Because up to four cubits of unfit roofing material can be considered an extension of the sukkah’s vertical walls, which are not subject to the same restrictions as the roof.

The mishnah brings three different examples to illustrate this rule:

(1) A house whose roof fell in, creating a hole in the center: If one places s’chach over the hole, the building can be used as a sukkah as long as the distance between the walls and the edge of the hole is less than four cubits.

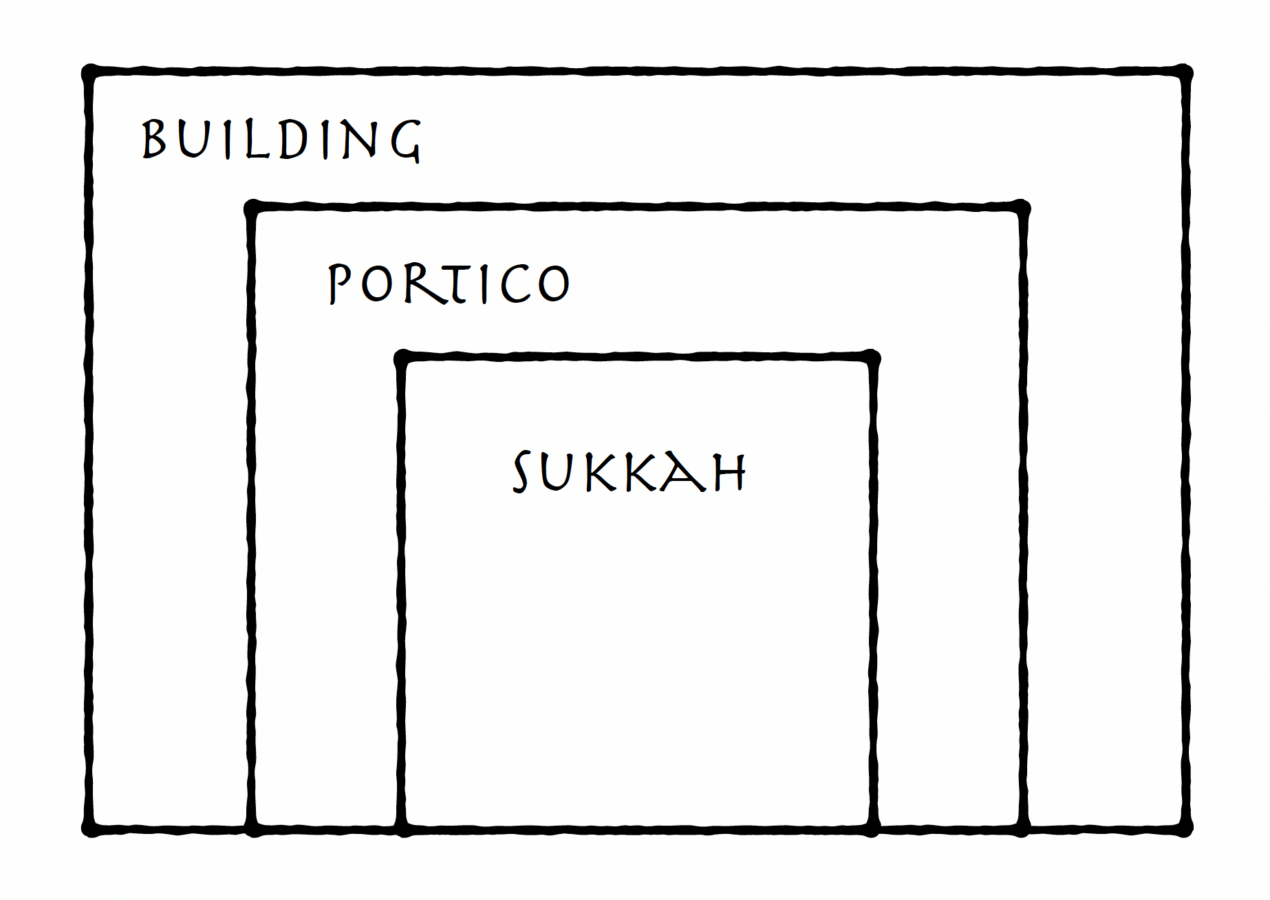

(2) A courtyard surrounded by a U-shaped portico (usually an extended covered porch supported by columns) which in turn is surrounded by a U-shaped building (see aerial perspective below): If the roof of the portico — i.e. the distance from the walls of the building to the internal edge of the portico — is less than four cubits, one can place s’chach over the courtyard to create a kosher sukkah.

(3) A large sukkah that has unfit roofing materials on the edge and kosher materials in the center: If the unfit materials are less than four cubits wide, the sukkah is kosher.

Naturally, the Gemara wants to know why all these examples have to be cited. All of these seem to demonstrate the broader principle that as long as the unfit roofing is less than four cubits wide and is located at the edge of the roof, the sukkah is kosher. Why do we need all three examples?

The answer is a little complicated.

If the mishnah had only taught the case about the house with the fallen roof, you might think the reason the sukkah is valid is because its walls were part of the original structure. So the mishnah cites the second example, where the sukkah is formed by the space inside the portico but its walls are the walls of the building to show that even if the walls are not part of the structure of the sukkah, the sukkah is valid. And without the third case, you might have thought that the first two cases dealt with roofing that would have been valid for a sukkah but for the fact that the roof was not built specifically for the purpose of the holiday. The third case is therefore necessary to teach that even if the materials are invalid for the purpose of a sukkah roof, the sukkah is still kosher so long as the invalid materials are less than four cubits wide.

The question about why all these examples are needed is actually a rhetorical device that reveals one of the Gemara’s underlying beliefs: If one example was sufficient to teach us what we need to know, there would only be one example. If the mishnah presents three, each additional one must come to teach us something unique. We saw another example of this kind of reasoning back on Yoma 84.

The rabbis apply this idea that every word has a unique lesson not only to the Mishnah, but to the Torah as well. Their approach to reading is not only interpretive, it is also generative. The drive to uncover the meaning of each and every word is a prime factor in the creation of the rabbinic corpus of Midrash and Talmud and is a uniquely Jewish approach to learning.

So why do we need all of these examples? To challenge us, as they did our ancestors, to read the text with a careful eye and unlock new and interesting ways to understand them.

Read all of Sukkah 17 on Sefaria.

This piece originally appeared in a My Jewish Learning Daf Yomi email newsletter sent on July 24th, 2021. If you are interested in receiving the newsletter, sign up here.

The post Sukkah 17 appeared first on My Jewish Learning.