Not all barbarians dress like terrorists.

That was the thought that kept running through my mind as I wandered through the world premiere of “Anne Frank: The Exhibition” at the Center for Jewish History last week. Opening on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which this year is the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, it’s the first full-scale replica of Anne Frank’s Annex.

The 7,500-square-foot multimedia installation was created by the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam in collaboration with the Center. While the original Annex remains empty, at Otto Frank’s request, the reconstruction contains more than 100 original artifacts — furniture, friendship albums, correspondence, a Torah — from the eight Jews who hid there for two years, July 1942 to August 1944.

The installation, up through April 30, traces Anne and her family from the 1920s in Frankfurt, Germany, through their flight to Amsterdam in 1934. Visitors explore five shadowy rooms, whose exact dimensions were copied from the Annex, down to the covered windows and bits of peeling wallpaper. A map of Europe, glowing beneath a glass floor, depicts the locations of every concentration camp; every site of genocide is marked with a small flag.

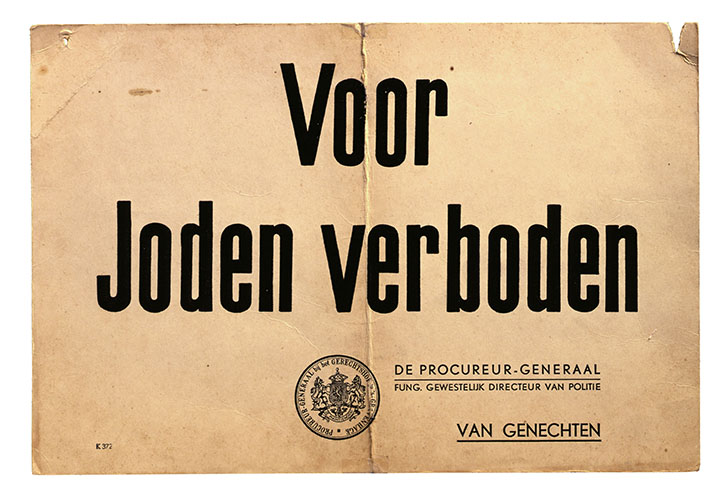

The array of signs in Dutch prohibiting Jews from entrance — “No entry for Jews”; “Jews forbidden”; “Jews not allowed”; “Jews not Dutch” — is particularly jarring.

After being deported, Anne and her sister Margot died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen, just months before the end of the war. Of the eight Jews who hid in the Annex, only Otto Frank survived. Miep Gies, who had helped those in hiding, had preserved Anne’s writings and shared them with him; a Dutch publisher released a version of the diary in 1947.

The exhibition displays 79 published editions of Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl,” which has been translated into dozens of languages and sold more than 30 million copies.

Otto Frank had requested that the spaces of the Annex, plundered by the Nazis, remain vacant, their barrenness attesting to the murder of 75% of Dutch Jews. One could take issue with the recreation, just as one could take issue with publishing the full diary against Otto’s wishes. But after the worst massacre since the Holocaust, when many seemingly intelligent people refuse to see it as such, one imagines that Otto would be focused on getting as many people to see it as possible. More than 250 school tours have already been booked.

At the same time, one can’t help but point out the fact that the original Annex admits 1.2 million visitors annually —while Amsterdam today is boiling with antisemitism.

Which brings us back to: not all barbarians dress like terrorists. I do believe that part of the shock of the post-Oct. 7 reaction stems from our own forgetting centuries of pre-Hamas persecution.

After the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961, Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe how ordinary people can commit evil acts by “just following orders.” Her thesis was that evil can become banal when it’s systematic and unthinking — when ordinary people participate in it without care or choice.

Arendt was admonished for her book and in my opinion rightly so. One just has to look at the photos of well-dressed Germans savagely — gleefully — beating Jews in the streets or the films shot by British and American soldiers upon liberating the camps to see the superficiality of her theory. The soldiers found corpses with eyes gouged out, bodies split open, and remnants of barbaric experimentations (hello, Candace). Even more telling, when the soldiers took groups of “ordinary” Germans to see the camps, the expressions on their faces were not of horror, but complacency.

When the soldiers took groups of “ordinary” Germans to see the camps, the expressions on their faces were not of horror, but complacency.

In the same vein, Russians were notorious for their glee while carrying out the most gruesome pogroms.

Contrary to Arendt, it seems that evil can be easily summoned when morality and/or intelligence is in short supply. One need look no further than many of the “professors” at Columbia, Harvard, and Yale.

Indeed, Germans at the time considered themselves highly educated. But education doesn’t necessarily track with civilized behavior; Marxists also consider themselves highly educated. The fact is, the “Good German” is a myth. The only good Germans were the ones who hid Judeans, not the ones “following orders.”

And so while this exhibition commemorates the worst genocide in history, it also helps to explain how “educated” leftists today can refuse to understand what the word genocide means — as they try to repeat it. And in Europe, there’s a good chance that the grandparents of today’s violent rioters were gleefully herding humans into gas chambers, just 80 years ago.

Some Germans took their own lives so they wouldn’t be forced to perform barbaric acts on innocents. Sadly, that’s one of the few civilized responses to evil. It’s a response we never hear about in the Islamic world. This set of enemies has been taught since birth to hate and kill Jews: they believe it’s religiously sanctioned.

Sophie Scholl, a student leader of the White Rose resistance group, was also religiously motivated to do everything possible to alert the world to what the Nazis were doing. “Laws change,” she said. “Conscience doesn’t.”

Sophie faced the Nazi guillotine for telling the truth. She was only a few years older than Anne. Anything that excuses barbarism in any of its forms merely mocks the righteousness of those who live their lives doing good deeds and bravely calling out evil. It’s not pleasant to think that gleeful savagery will no doubt return with every generation. But understanding this truth is the only way to move forward.

Karen Lehrman Bloch is editor in chief of White Rose Magazine.