(New York Jewish Week) — Diamonds may be forever, but do you know what else lasts a pretty darn long time? Faux flowers.

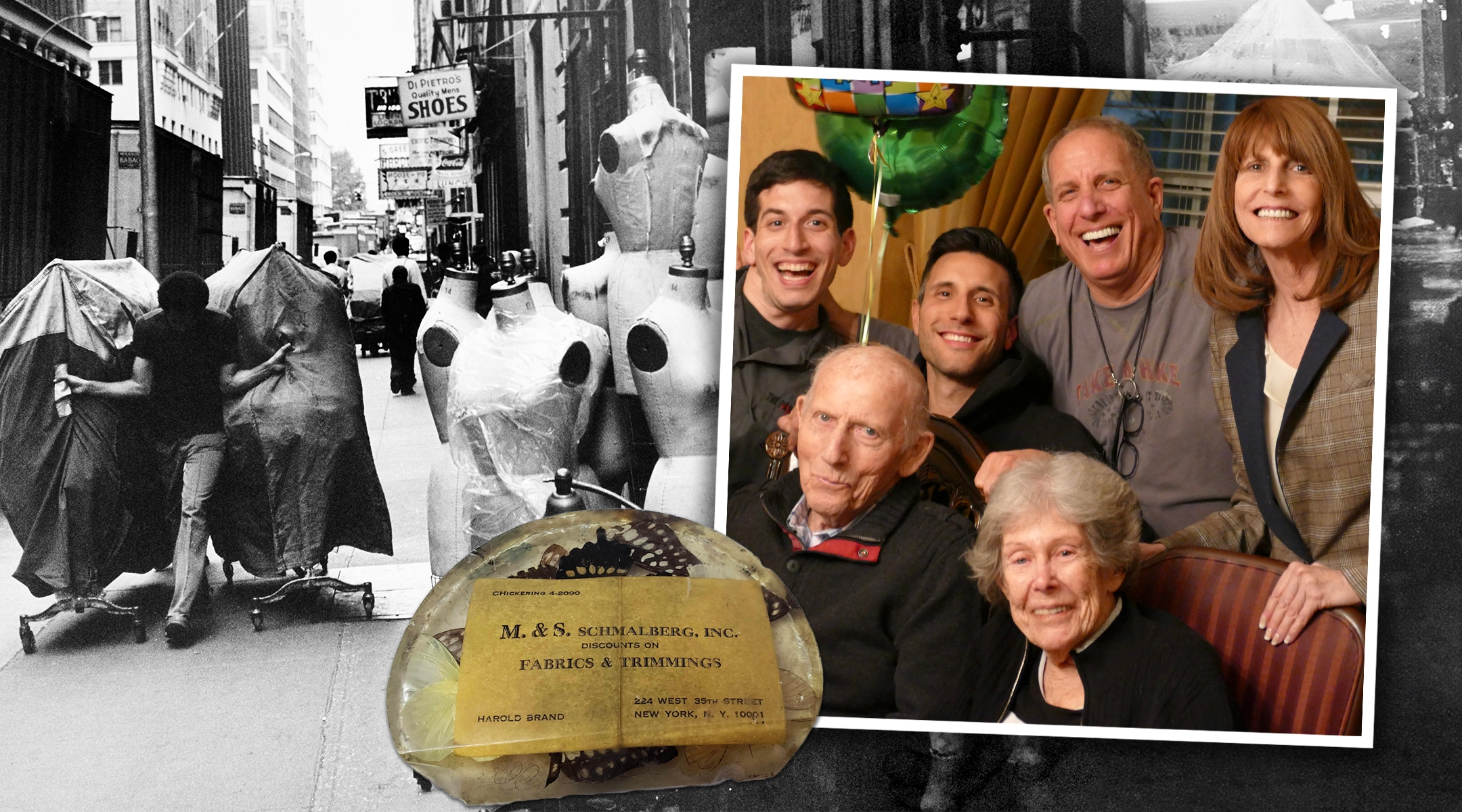

Just ask M&S Schmalberg, a Garment District-based artificial flower business that’s been owned and operated by the same Jewish family for 107 years.

At the family’s factory at 242 West 36th St., Adam Brand, a fourth-generation owner, is making artificial flowers much in the same way his ancestors did when they first opened in 1916.

“I love this place,” said Brand, a 40-year-old born-and-bred New Yorker, his passion for the craft palpable.

The colorful atelier, which occupies a large, seventh-floor space in a mid-block building just north of Penn Station, is adorned with artificial flowers of all hues. The blooms run the gamut from pastels to primary colors and are made of just about any fabric imaginable, from leather to lace. In one area, faux flowers are on display Roy G. Biv-style, in the colors of the rainbow, while in the center of it all sits Brand’s desk, which is decorated with generations of family photos and snapshots of the factory’s earlier eras.

The flowers themselves are bought by designer labels, costume designers, milliners and regular, flower-loving folk who, say, prefer a wedding bouquet or boutonniere that lasts longer than some marriages.

M&S Schmalberg was started by Brand’s great-great uncles, brothers Morris and Sam Schmalberg. At the time, the majority of the business was custom wholesale orders of fabric flowers for the garment trade. Following World War II, they were joined in the factory by Brand’s Polish Jewish grandfather, Harold Brand, who survived the Holocaust and moved to New York.

“He lost his mother, his father, two brothers and a sister,” Brand said. “I’ve said that a lot of times; it’s easy to forget these were real people that I should have met. They should have been my aunts and uncles.”

Harold Brand started working at the flower factory at age 17 and eventually became the second-generation owner of M&S Schmalberg along with his wife, Renee.

“He was a sweet man, a good man, a survivor through and through,” Adam Brand said, describing how, during periods when faux flowers were not en vogue, his “incredibly likable” grandfather would keep the business afloat by buying and selling Christmas wreaths, Arnold Palmer T-shirts — anything to stay in the black.

In 1981, Harold Brand was shot breaking up a dispute between two employees. He survived but was left with a long-term injury — sparking the transition to M&S Schmalberg’s third-generation owners, Brand’s father, Warren, and his aunt, Debra.

Adam Brand had his first experiences working at M&S Schmalberg some 20 years ago, on summer break as a college student, “when “Sex and the City’ was popular and there were flowers everywhere,” he said. He’s been at the helm of the business for about five years now.

Support the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom depends on readers like you. Make a donation now to support independent Jewish journalism in New York.

Brand sees himself as carrying on a long Jewish legacy in the neighborhood and the industry. “There’s a lot of other Jewish people who work in the Garment District,” he told the New York Jewish Week. “Part of the M&S Schmalberg history is being Jewish.”

Fashion is fickle — since M&S Schmalberg first opened, the rhythm of the factory has altered according to whether or not artificial flowers are popular at any given moment. But over the course of a century-plus in business, “Everything has changed,” Brand said. “The Garment District has changed, the factory has changed, our entire operation has changed.”

New York City was once a major center of clothing production: By 1897, some 75 percent of the workers in the apparel industry were Jewish, and most of these operations were centered downtown, below 14th Street. Midtown’s Garment District dates to 1919, when it was created in a formerly rough-and-tumble neighborhood known as the Tenderloin; developers raced to construct an industrial “city within the city” and, by 1926, the Garment District was the fastest growing site of construction all of New York City, according to the Garment District Alliance.

By 2018, according to the Alliance, apparel manufacturing accounted for just 4% of jobs in the Garment District. It’s a change Brand has observed first-hand. “Going back as little as 20, 30 years ago, so many of our clients were in NYC,” he added. “You’d get an order, you’d produce hundreds or thousands of flowers, you’d box them up, you’d take a hand truck down the block to wherever the client was.”

Today, though the apparel industry has largely left New York, such orders remain “a small piece of what we do,” he said. “We still do a lot of fashion production, a lot fashion design, especially for the Met Gala, for runway — we’re working on some Fashion Week stuff now. “

In a new twist, much of the business has shifted toward costume design. According to Brand, two years ago their biggest client was the San Francisco Opera; M&S Schmalberg has also made custom flowers for Broadway’s “Hamilton” as well as TV shows including “Bridgerton” and “The Gilded Age.”

The company, which presently employs 16 people, also makes faux flowers for individual clients — M&S Schmalberg flowers can be purchased via Etsy, Amazon or their own website. “We have people reaching out with heirloom garments,” he said. “I’ve had people send us their grandmother’s wedding dress, the shirt they wore when they met their spouse… Anything you can think of, we can make flowers out of it.”

Brand then gamely walked the New York Jewish Week through the process of creating artificial flowers — the business still uses molds that date to the company’s founding. He demonstrates how, by combining and using different molds — to say nothing of the endless variety of fabrics — the assortment of flowers M&S Schmalberg can create is quite literally limitless.

But perhaps Brand’s greatest pleasure is showing visitors how the magic happens. “If you’re a New Yorker and you’re intrigued, you can just come here and say hello,” he said. “I love giving tours of the factory. It’s become a big part of what we do, sharing the craft.”

“Fifty years ago, we weren’t that unique — we were one of many,” he added. “Today, for a variety of reasons, there’s nobody else left in New York making flowers like this. It’s sad what happened to the Garment District, but it makes us unique.”